"Big things have small beginnings." So says Michael Fassbender's character in Prometheus. He was referring to a blob of alien goo that would go on to spawn the monster that drives the Alien series, but he just as easily could've been talking about Radiohead.

Like that daub of black goo, Radiohead's origins were inauspicious. The band -- consisting throughout its existence of Thom Yorke (vocals, guitar, piano, electronics), Jonny Greenwood (lead guitar, various other instruments), Colin Greenwood (bass, synths), Ed O'Brien (guitar, backing vocals), and Phil Selway (drums) -- formed in 1985 in the music rehearsal room of their Oxfordshire boys' school. The band's awkward original moniker was On A Friday -- their usual practice time.

Unlike so many of their contemporaries, On A Friday did not spend years slugging it out in the indie tour circuit before achieving broader success -- their path to glory was more in the classic-rock mold. After a university-born hiatus through the late '80s, On A Friday signed a six-album deal with EMI without ever touring. Pressured by their label, the band changed their name to Radiohead, after a Talking Heads song. A year later, the band recorded a song called "Creep," and the rest is history.

When most people think of Radiohead now, they think of Radiohead the iconoclasts: the band that resurrected progressive rock with OK Computer, dove headlong into experimental music with Kid A, and precipitated an entirely new business model with In Rainbows. For a high-profile band with so much to lose, Radiohead has historically been relentlessly ambitious. No two of their albums sound alike. (Not even Kid A and Amnesiac -- more on that later.)

But Radiohead has achieved their status as one of the last consensus-building rock bands because of their broad populist streak. That populism is musical as well as political. Even at their most challenging and experimental, Radiohead ruthlessly edits their music into catchy, pop-sized chunks. Beneath the swathes of digital gauze and strange sound is a Beatles-style hit machine.

After eight albums, Radiohead may be close to the end of their creative arc. The band has expressed growing (and characteristic!) dissatisfaction with the process of writing and recording albums. Said Yorke during the press cycle for The King Of Limbs: "None of us want to go into that creative hoo-hah of a long-play record again … I mean, it's just become a real drag." (Then again, The King Of Limbs concludes with Yorke informing the listener that, "If you think this is over, then you're wrong.")

So now is as good of a time as any to reflect on Radiohead's catalog. Here are all eight of their full-length albums, analyzed and examined, and ranked from worst to best. If you disagree -- and oh, will some of you ever disagree -- then feel free to crush my list like a bug in the ground with your comments.

7. Pablo Honey (1993)

Pablo Honey, Radiohead's first album, routinely gets knocked as their worst. Really, though, its middling reputation comes partially due to circumstance. It preceded one of the most fertile creative runs in rock history; few albums wouldn't pale in comparison. Pablo Honey also suffered from poor timing. Grunge was peaking when it came out in '93. Its alterna-rock pose, and especially its ubiquitous single "Creep," drew plenty of unflattering comparisons.

And Pablo Honey is not without flaws. Radiohead's identity was still malleable at the time. Their influences -- U2, Scott Walker, the Smiths, -- push through into pastiche territory at times. The self-pitying lyrics sound weirdly naïve next to the cynicism of their later material. Pablo Honey also suffers from inconsistent songwriting. Its second half is noticeably less well-developed than its first -- the same problem The King Of Limbs would suffer from 18 years later.

But despite its adolescent character, Pablo Honey remains a charming and occasionally brilliant rock album. Their youth brought vigor as well as naïveté; Thom Yorke belts out his lines with such force that his more recent recordings sound thin by comparison. Overplayed though it is, "Creep" remains one of Radiohead's finest hours -- Yorke's vocal crescendo in the bridge still raises goosebumps. "Anyone Can Play Guitar," meanwhile, foreshadows the apocalyptic themes that would color the band's coming creative storm: "And if the world does turn / and if London burns / I'll be standing on the beach with my guitar."

6. In Rainbows (2007)

History will remember In Rainbows as much for the circumstances of its release as for its content. When Radiohead split with EMI after Hail To The Thief (Thom Yorke dismissed the label as "genteel arms manufacturers who treated music as a nice side project"), they were left to devise a new means of distributing their music. The pay-what-you-want download model they settled on literally changed the game, as countless Bandcamps can attest.

Though In Rainbows sported a unique business model upon its release, it's a musically conservative album by Radiohead standards. After four albums in a row of sonic and procedural experimentation, In Rainbows marked a return to streamlined pop songwriting. It continues Hail To The Thief's combination of analog rock and digital programming, but its arrangements breathe more freely -- Yorke's vocal melodies take the lead, while the digital textures modify rock instruments rather than standing in for them.

The suffocating political paranoia of In Rainbows's predecessor is largely gone as well. In its place are quotidian concerns: loneliness, unrequited romance, and dissatisfaction with everyday pleasures. When paired with the stripped-down arrangements, these themes sometimes feel like small potatoes by Radiohead standards; the bland single "House of Cards" in particular suffers from this problem. Weirdly, Radiohead also relegated some of the album's best songs to its bonus second disc. But at its best, In Rainbows offers thrilling jitters ("15 Step," "Bodysnatchers," "Bangers And Mash") and aching catharsis from Yorke ("Nude," "Reckoner," "Last Flowers").

5. Amnesiac (2001)

Like Pablo Honey, Amnesiac is something of a victim of circumstance. It was recorded during the same sessions asKid A and was released just a year later. Consequently, Amnesiac is frequently written off as a B-sides collection -- an impression that its clunky reworking of the Kid A track "Morning Bell" reinforces.

But aside from the "Morning Bell" misstep, Amnesiac is a grossly underrated album with its own personality -- tauter than In Rainbows, starker than The King Of Limbs, and better-developed than Pablo Honey. There's plenty of Kid A-styled programming here, especially on opener "Pakt Like Sardines In A Crushed Tin Can" and in the nauseating churn of "Pulk/Pull Revolving Doors." Other cuts allow more air inside; "I Might Be Wrong" and "Knives Out" unfold from clattery single-coil riffs. "Pyramid Song" remains a fan favorite; according to Ed O'Brien, Yorke once called it "the best thing we've committed to tape, ever."

Amnesiac's most striking feature may be the anger that bubbles beneath its surface. Where Kid A consigned itself to fate, Amnesiac simmers with barely suppressed rage. Yorke's little-man protagonists get belligerent in the face of their own abjection. "I'm a reasonable man, get off my case," he insists on "Pakt Like Sardines." He even beats his chest on "You And Whose Army?" -- "Come on if you think / you can take us on." "Dollars and Cents" sees him switching perspective, speaking for callous market forces: "We are the dollars and cents, and the pounds and pence, and the mark and yen / We're gonna crack your little souls, yeah, we're gonna crack your little souls." Yikes.

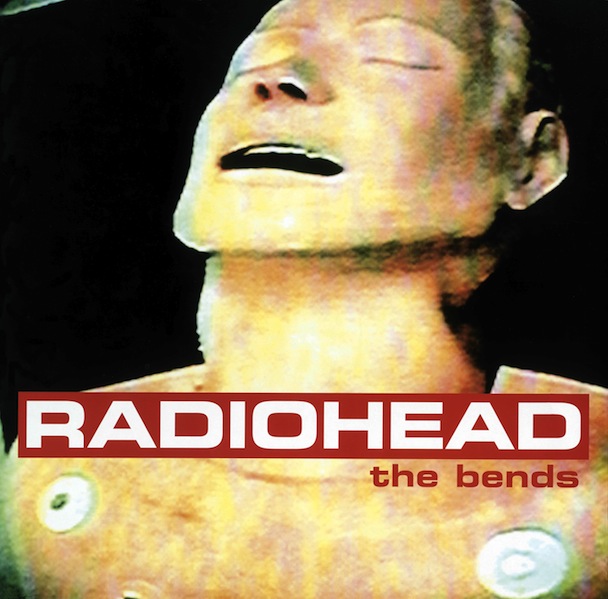

4. The Bends (1995)

After Pablo Honey became a moderate chart success, Radiohead found themselves supporting it in a nigh-endless touring cycle. True to form, the band developed distaste for the shallowness of the touring musician's lifestyle. Out of this revulsion came The Bends, Radiohead's first truly great album.

Like its predecessor, The Bends is a guitar-driven alternative rock album. Phil Selway's drums still sound organic, and Johnny Greenwood contributes ear-slicing solos that would go extinct just two albums later. But where Pablo Honey was conventional enough to draw "Nirvana-lite" digs, The Bends is stranger and spookier. It's Radiohead's first collaboration with Nigel Godrich, who worked under head producer John Leckie. Still, his presence shows -- the band's experimentation with druggy layering starts with "Planet Telex," The Bends's fantastic opener.

And while Pablo Honey's soaring U2-isms crop up in places ("Bones," "Sulk"), The Bends's tone skews dark. Thom Yorke turned his attention away from his navel and toward the scary world around him for the first time here. The fan-favorite closer "Street Spirit (Fade Out)," he once said, "has no resolve. It is the dark tunnel without the light at the end … it's about staring the fucking devil right in the eyes, and knowing that no matter what the hell you do, he'll get the last laugh."

This combination of ingredients -- rock + vibes + terror -- produced some of Radiohead's most indelible songs. Quite a few of them, including "Planet Telex," "Street Spirit," "My Iron Lung," and the painfully sweet "Fake Plastic Trees," are right here.

3. Hail To The Thief (2003)

Radiohead's creative process places a premium on revision; each song receives multiple treatments before reaching completion. The Kid A/Amnesiac period was especially grueling. The band spent long hours clustered around computers, watching while individual members programmed tracks.

Radiohead consequently dispensed with the rewrites on Hail To The Thief. They recorded the album in just two weeks, denying themselves the endless revisions. Next to its hermetic predecessors, Hail To The Thief sounds positively raw -- compare the orderly sine waves that introduce "Everything In Its Right Place" to Jonny's guitar static at the beginning of "2+2=5."

With its 15-song, 56-minute runtime, Hail To The Thief is liable to lose listeners here and there. (The band's members have occasionally expressed regret that they didn't pare the album down.) Nonetheless, it showcases Radiohead's many strengths better than any other album in their discography. Hail To The Thief is the first blend of Kid A-era programming and the guitar rock of their early work. It sports the most diverse set of any Radiohead album: spiky and erratic on "2+2=5" and "Myxomatosis"; funereal on "We Suck Young Blood" and "I Will"; nail-biting on "The Gloaming" and "Wolf At The Door."

The schizophrenic mood matches Yorke's lyrics, which deal with the unease he felt as the US and UK invaded Iraq and ramped up their domestic security states. Hail To The Thief is a rarity -- a political album that's impressionistic, rather than didactic. It remains a poignant memento of the anxiety that gripped both countries at the onset of the War On Terror.

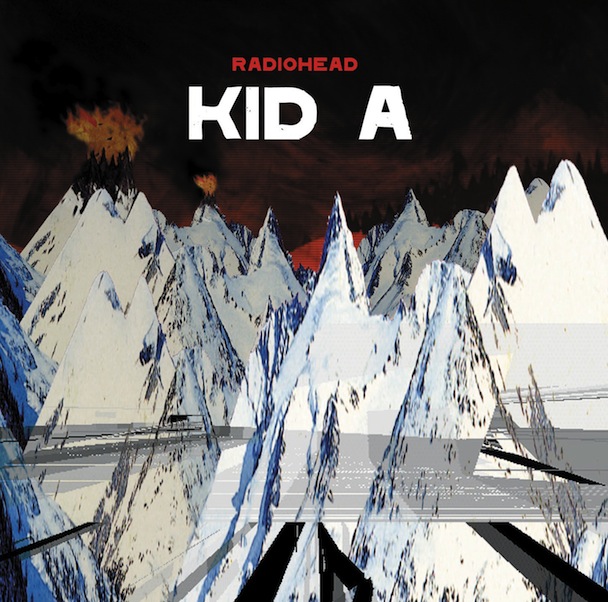

2. Kid A (2000)

Few albums in the rock annals are as imposing as Kid A. I clearly remember the first time I saw its cover art, fresh out of a blind-ordered box -- the crystalline peaks and pixilated explosions paradoxically suggested icy reserve and blistering intensity at the same time. The lunatic cartoons hidden in the packaging made it even creepier. Fortunately, the music within lived up to the physical object's grim promise.

Kid A was an impossibly gutsy career move for Radiohead. It all but drops the blaring guitars and acoustic drums that propelled the critically revered OK Computer. In their place is an electronic wilderness: glassy synthetic beats, glitchified vocal loops, and bizarre textural experiments ("Motion Picture Soundtrack" and the lightless, airless "Treefingers"). If OK Computer chronicles the modern struggle between humanity and technology, Kid A documents the triumph of the machines.

But Radiohead's spirit survives even in this wasteland. Kid A succeeds so spectacularly not because it dabbles in krautrock, jazz, and ambient, but because it constructs such catchy songs from those influences. "Idioteque" simultaneously foreshadows and belittles the impending popularity of EDM among Radiohead's fanbase. The comparatively rock-ish "In Limbo" dissolves into a horrifying cacophony. So too does "The National Anthem," which is perhaps the most sinister song Radiohead have ever recorded. Thom Yorke took over bass duties from Colin Greenwood for the song's legendary bass line, which the singer wrote as a 16-year-old. These songs offered a crash course in outré sound for a whole generation of music fans; their influence continues to reverberate today.

1. OK Computer (1997)

OK Computer is virtually impossible to talk about in 2012. It has been so thoroughly analyzed and debated and re-analyzed that there just isn't much left to say; it's become an axiomatic feature of the landscape, like Sgt. Pepper's or Dark Side Of The Moon. Deservedly so. OK Computer is the best album in Radiohead's catalog, and one of the best rock albums ever recorded.

This album is also tough to describe because it's difficult to know where to start. Pointing out OK Computer's highlights doesn't work -- every song here is a masterstroke. Summarizing its aesthetic isn't much easier. Radiohead was still firmly in the rock camp at this juncture, but OK Computer bursts with countless experimental touches: vocoders, cut-up drums, extra instrumentation, chorus-less structures, odd time signatures, and inexplicable whooshes and swooshes. The music's gearhead inclinations contrast markedly with the lyrics, which obsess over the emotionally stifling effects of modern technology and the vapidity of consumer culture.

Weirdly, OK Computer hasn't inspired much direct imitation during the 15 years since it came out. Its immediate predecessor and successor -- The Bends and Kid A, respectively -- have spread their seed further in that respect. Nonetheless, it has aged incredibly well, thanks both to its remarkable songwriting and to its creepily predictive subject matter. Though it came out during the booming 1990s, its concerns are thoroughly 21st century. It nails the vague dreads and cultural numbness of the post-9/11 era as few albums since have. OK Computer heralded the new millennium -- it serves as prophecy, indictment, and threnody for our current malaise, all at once.