- G-Unit/Aftermath/Interscope

- 2005

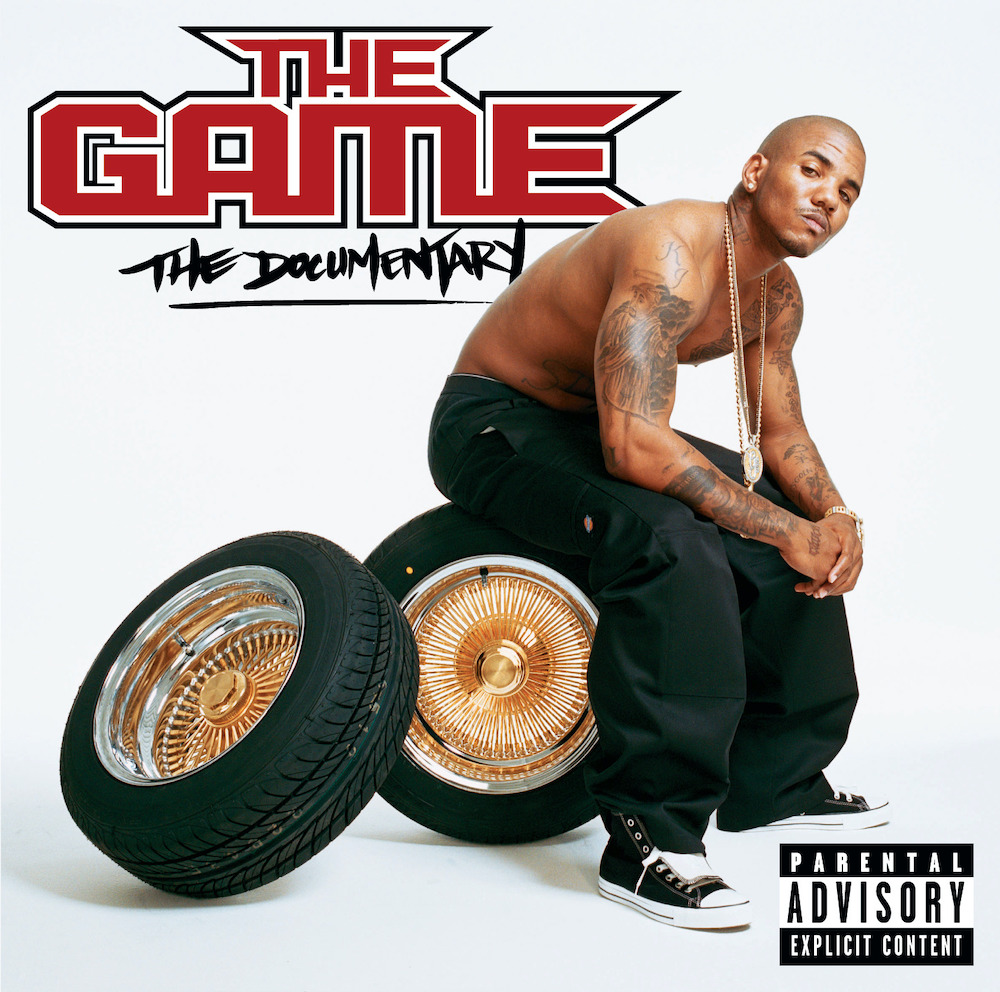

It almost seemed like an expensive experiment: If all of the forces of the music industry lined up behind one clunky and workmanlike rapper, could they turn him into a towering star? Could they build a blockbuster around relatively off-putting presence? Was 50 Cent a one-off phenomenon, or could they build another 50 Cent, as long as they had active participation from the actual 50 Cent? They could. They did. The Game's A-list stardom wasn't fated to last, but he managed to make one beautiful, gleaming illustration of how powerful the world's biggest rap producers were in the mid-'00s. The brand could not be managed, and the story won't make anyone feel great, but the music banged.

This Saturday marks 20 years since the unimaginatively monikered Compton rapper known as the Game released his unimaginatively titled debut album The Documentary. Even today, the record's credits are staggering. Consider the producers: Dr. Dre, Kanye West, Timbaland, Just Blaze, Scott Storch, Havoc, Hi-Tek, Mike Elizondo, Eminem. None of them were handing out the stuff they had buried in desktop files, either. These people were all operating at an extremely high capacity, and they were all giving the Game the best that they had to offer. More importantly, 50 Cent, then on the run of a lifetime, allowed Game into his flourishing G-Unit empire and helped craft a few huge, glittering anthems for him -- anthems that 50 soon presumably wished he'd kept for himself. The arrangement was unsustainable, but the result felt colossal.

You could see the calculations that the behind-the-scenes forces were making. Those calculations were part of the story, and they were part of the product. Nobody was trying to hide anything. This was a moment when figures like 50 Cent were demonstrating just how lucrative a well-crafted rap persona could be, and their embrace of capitalistic excess became inextricable from the art. With Game, you could dollar signs appearing in people's eyes. Here was a guy who basically had 50 Cent's look and backstory. He'd spent time in the trenches, and he'd recovered from multiple gunshot wounds. He was tall and muscular and handsome and frequently shirtless, and he even looked a bit like 50. As a Compton native with loud gang affiliations, Game could present himself as a West Coast version of 50. Could he rap? Who cares? We'll fix it in post.

Jayceon Taylor was just 25 when he got famous, but he'd already been a music-industry project for years. The man who would become the Game was born into a Compton family that was heavy in the gang world, and he was in and out of foster homes as a kid. Game graduated high school and had a bit of college, but he also got himself into the street economy as a young man. In 2001, the 21-year-old Game was shot five times in the drug-house robbery that he later dramatized in his "Dreams" video. Game spent a few days in a coma, and while he was recovering, the story is that he got his brother Big Fase 100 to buy him the full canon of classic rap albums: Ready To Die, Reasonable Doubt, Doggystyle, all the greatest hits. Working his way back to health, he obsessively studied those albums, envisioning the day when he'd get to make one himself.

The last part of that story might be the Game's one real innovation, if you can call it that. At least in my memory, rappers didn't rap about making classic rap albums before Game. Instead, the pantheon of rap classics was fodder for magazine articles and barbershop discussions. It wasn't part of the text. Rap records were responsive, in-the-moment. The true classic rap albums were made by people trying to come up in the world and make their cities and neighborhoods proud. They weren't necessarily trying to build monumental works of art that would stand for generations.

50 Cent, Game's most important benefactor, never worried about that at all. He was trying to talk shit and make hits, and those two goals often overlapped. Get Rich Or Die Tryin' wasn't a classic album because 50 Cent wanted to make a classic album. It's a classic album because 50 was absolutely on fire when he made it and because it made a cultural impact that many of us remember fondly. But Game was different. All through The Documentary, Game continuously shouts out his rap peers and influences, even reaching hard to cram a bunch of important album titles into one very labored chorus: "Until they sign my Death Certificate, All Eyez On Me/ I'm still at it, Illmatic, and that's The Documentary." It made for an awkward dissonance: A street-rap outlaw who carried himself like a grade-grubbing honor student.

The Game named himself after the 1997 David Fincher movie -- his grandmother was a fan -- and hit the mixtape circuit. He recorded a bunch of material with Bay Area impresario JT The Bigga Figga. He made a demo that got attention from Bad Boy, to the point where Game later claimed that he spent years following Diddy around before figuring that the man wasn't actually going to sign him. Instead, he eventually forged a connection with fellow Compton native Dr. Dre, a man who he always seemed faintly desperate to impress.

Game's timing was good. He joined the Aftermath stable around the same time that 50 Cent was recording Get Rich Or Die Tryin', and you can see him standing around in the background in 50's "In Da Club" video. But the Game wasn't fast-tracked to mainstream stardom in the way that 50 was. Instead, Game took up space on the Aftermath shelf for a couple of years, cranking out endless reams of material and making appearances on Whoo Kid and Green Lantern mixtapes. I'm pretty sure the first time I heard Game's voice was alongside Jim Jones and Cam'ron on the 2003 single "Certified Gangstas." That's a hard song.

Even on "Certified Gangstas," the Game's hero-worship is on full display. The track is built on an Eazy-E sample, and the video restages the convenience store scene from Menace II Society. For Cam'ron and Jim Jones, this was a chance to play around with old-school California gangsta-rap aesthetics. For Game, it was a way of life. Even in the way that Game flaunts his gang affiliations, it seems like he's working to live up to the image that he's already built in his mind. But as he reveled in West Coast aesthetics, Game rapped in a straightforward rasp that recalled East Coast giants like Nas. Maybe he was thinking strategically, in terms of different markets, or maybe that's just how your voice sounds when you learn to rap by studying the canon.

"Certified Gangstas" wasn't really a hit, but it was an outlier -- a track with a Game verse that actually got a commercial release and a smidgen of radio play. In his early Aftermath tenure, Game's music mostly found its way onto mixtapes. He kept hustling, rapping in front of anyone with pull, and he forged a few connections. At one Beverly Hills party, Game battled Kanye West, another guy who was trying to hustle his way off the shelf. Game later said that he lost that battle, but he and West became close after that meet-cute. Kanye produced "Dreams," which would become one of the bigger tracks on The Documentary. Before that, a pre-fame Game showed up in a Boost Mobile commercial with Kanye and Ludacris. The connection remains. As I write this, the Game's most recent Hot 100 hit is "Eazy" a Kanye West collab from 2022.

Eventually, the Game's hustle impressed Dr. Dre, and Dre earnestly started the work of turning Game into a star. But Dre wasn't the one who convinced 50 Cent to add Game to G-Unit. That was Jimmy Iovine, the Interscope label boss who observed that everything 50 touched turned to gold. Soon after Get Rich Or Die Tryin' had its wildly successful moment, the G-Unit group album Beg For Mercy nearly outsold Jay-Z's Black Album in its first week. 50's reflected glory was enough to briefly turn his Queens cronies Lloyd Banks and Tony Yayo into stars, though Yayo's ascent was complicated by his badly timed incarceration. With an eye on the growing Southern market, 50 also brought Nashville native Young Buck into the group. I have to imagine that 50 made a similar calculation when he agreed to let the Game into G-Unit.

Game made guest appearances on the Lloyd Banks and Young Buck albums, both of which were obvious first-day purchases for fans like me. But the Game wasn't positioned as a 50 Cent subordinate, and that would later cause problems. Instead, Game was working closely with Dr. Dre, getting the best of what Dre had to offer. "Westside Story," the first Game track that Dre produced, got a big boost when 50 Cent appeared on the hook, and it made it onto the lower rungs of the Hot 100 as a street single with no video. The contrast between Game's gruff hunger and 50's devil-may-care slickness became a potent force. A pattern emerged: Game sounded a lot better when 50 was around.

The Game's 50 Cent collaborations were typically the best songs that either artist was recording around that time. Later on, 50 claimed credit for all of Game's biggest hits, and he had a case. For years, the two of them sniped at each other over who wrote what. In the moment, though, they made magic. The 50/Game collab "How We Do" became a true crossover hit, reaching #4 during the run-up to Game's album release. I love that song -- the sinister plinks and handclaps, the shivery Dr. Dre strings, the stickily catchy singsong hook. 50 effortlessly outshines Game at every turn: "I put Lamborghini gull doors on the Es-co-lade." But Game sits right in the track's pocket, and his grunt sounds great. "How We Do" wouldn't work as well as a solo 50 Cent song. The slickness is all in the back-and-forth chemistry between two guys who would soon hate each other.

"How We Do" set The Documentary up beautifully. When the album arrived in January 2005, it was a prefabricated star-is-born moment. To this day, the beats on that album are simply amazing. "Church For Thugs" is a prime triumphal Just Blaze soul-sample anthem, with the adrenaline cranked all the way up. Buckwild's chopped-up strings and guitars on the sincere closer "Like Father, Like Son" are simply beautiful. "We Ain't" has a wild Eminem guest-verse that had Game rapping about Em murdering him on his own shit, and the pounding synth-beat is one of my favorite Eminem productions. Timbaland makes "Put You On The Game" just monstrously catchy; I love how he asks if Compton's in the house.

Dr. Dre mixed the record and produced a bunch of its tracks, shining everything up to a crisp gleam. There's nothing definitively West Coast about the sound of The Documentary. It's the apex of post-regional '00s rap production, a time-capsule reminder of the moment that rap was still stepping into its new role as the lingua franca for global pop music. But you can't get around the fact that this masterful production went to the Game. As a rapper, Game had fire and charisma, and you can hear why all these important music-industry forces strapped the rocketship onto him. But there's something unctuous and uncomfortable about the way Game presents himself throughout.

At the time, the one thing that everyone mentioned was Game's constant namedropping. He couldn't get through one line without referencing another song, album, or rapper. You can practically hear him bolding the famous names like a gossip columnist. But it's not just Game's constant use of those names that jumps out. It's the effect of that whole approach. Game invokes these other rappers' names as worshipful lodestars, goals to be achieved. Then he mentions himself alongside them, as if he's trying to convince himself that he belongs among their number. One moment, he throws subliminal shots at Jay-Z. The next, he insists that he's not throwing shots and reverently calls back to Reasonable Doubt. It's stressful.

I reviewed The Documentary for Pitchfork, and I arrived at the same conclusion as a lot of critics: It was an expertly-assembled mega-budget album built around a fairly mediocre central performance. Given the strength of the production, that was still enough to make it a great rap record. Listening back now, there's a compelling drama at work in The Documentary. Game sounds like an everyman, a fan who's desperately trying to convince himself that he's a titan. What if Stan really did become close with Eminem? What if he was treated as a peer and as a sure commercial bet? What if he still didn't really believe in himself? Maybe I'm over-analyzing, but The Documentary is a fun album to over-analyze. It's all there in the record's best song and biggest hit.

"Hate It Or Love It," another back-and-forth between 50 Cent and the Game, is a straight-up rap masterpiece, one of the best songs of its era. Dr. Dre and Cool & Dre -- no relation -- build bittersweet symphonies out of strings and moans sampled from an old Trammps record. 50's opening verse is a panoramic depiction of a vulnerable little kid growing up in confusing and dangerous circumstances. Game's philosophical musings are way clumsier. He says, "No schoolbooks, they use that wood to build coffins," as if that's how that works. Still, there's real pain and determination in his voice, and it bumps up perfectly against 50's indelible chorus. I still feel transported whenever I hear it.

In the end, maybe The Documentary was too successful. It came out of the gate with sales of more than half a million in its first week, upstaging every other G-Unit record other than 50's own Get Rich Or Die Tryin'. As it happened, 50 Cent was getting ready to release his follow-up The St. Valentine's Day Massacre a few weeks later, and the songs that he recorded with the Game kept overshadowing the ones that he kept for himself. In the end, 50 had to push his album release back and give it the way-more-generic title The Massacre. It still sold like crazy, but it didn't have the Get Rich magic. Through Game, 50 Cent was essentially forced to compete with himself, and he didn't like the way it turned out.

As loudly as he repped G-Unit, the Game wasn't close with 50 Cent the way that Lloyd Banks and Tony Yayo were. When asked about 50's complicated web of feuds, Game would say that he didn't have any part in it. While working on the mixtape circuit, he'd become friendly with guys like Jadakiss and Fat Joe, and 50 wasn't cool with those guys. When Game made interview comments that 50 deemed insufficiently respectful, 50 went on New York radio and announced that he was kicking Game out of G-Unit when The Documentary was barely a month old. The Game was in New York at the time, and he heard 50's announcement on the radio, so he stormed into the Hot 97 studios with his goons. In that office hallway, the Game and 50 Cent's camps got into a literal shootout. One of Game's associates got hit in the leg, and it seems miraculous in retrospect that nobody died.

Shortly after the shootout, Game and 50 Cent announced a truce at a strained press conference, but they were right back to taking verbal shots at each other almost immediately. On the insane mixtape track "300 Barz And Running," Game spent 15 minutes insulting 50 Cent, his remaining G-Unit comrades, and everyone else who was on his nerves at the time. Game dedicated his entire set at Hot 97's 2005 Summer Jam to trying to coin the "G-U-Not" catchphrase, without success. Even for those of us who love rap beef, it seemed excessive. It was exhausting.

The 50 Cent/Game psychodrama continued for years, until neither one of them was especially relevant anymore. The Documentary went double platinum, but the Game's dramatic tendencies continually got the better of him. His 2006 sophomore album The Doctor's Advocate had some real bangers, but it was still an album called The Doctor's Advocate that didn't have any Dr. Dre beats. Game burned bridge after bridge, and he was conspicuously absent from Dre's Super Bowl Halftime Show a few years ago. Still, Game kept working and made occasional hits by latching onto allies like Kanye West and Drake. Thanks to that Drake association, Game might've been the only prominent West Coast rapper who didn't get a boost from last year's Drake/Kendrick feud.

The Game's determination to win is what led to the creation of The Documentary, which still stands as a truly great rap record two decades later. It has also led to the man himself, still looking good in middle age, taking part in embarrassing fads. His latest thing is to court virality by going DIY-vigilante Chris Hansen, beating up and intimidating accused child molesters on camera. He never learned to project the confidence of the idols who he vocally admired. Then again, he still made The Documentary. We won't be writing 20th-anniversary pieces about any other Game album, but that one record still sounds great. The experiment was a success.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!