- TDE/Aftermath/Interscope

- 2015

From the moment that Kendrick Lamar gained major label recognition, he was ordained as a leader, both for his Compton stomping grounds and for hip-hop as a whole. After the release of his album Section.80, the West Coast icons he looked up to growing up — Snoop Dogg, Dr. Dre, the Game, Kurupt — formally passed the torch to Kendrick on stage at Music Box Theatre in Los Angeles. And after the release of his brilliant Aftermath debut good kid, m.A.A.d city, his status was further fortified: He had spiritual and religious foundations without being preachy, he had prodigious storytelling abilities, and he could still make his own brand of bangers. On "The Heart Pt. 3," released weeks before GKMC, he gave thought to his impending role as one of hip-hop's new cultural generals. "When the whole world see you as Pac reincarnated, that's enough pressure to live your whole life sedated," he rapped. Released 10 years ago this Saturday, his second album, To Pimp A Butterfly, was an even deeper meditation on Black leadership, released during a time in the country that desperately needed it.

TPAB showed just how far Kendrick was willing to chart his own path. When good kid, m.A.A.d city dropped, it felt like one of the most adventurous albums that hip-hop had to offer: a concept album about faith that employed nonlinear storytelling, with a lead single that warned about the pitfalls of alcoholism. But compared to To Pimp A Butterfly, GKMC was more conventional than anyone could realize. Some of its best analogies come in television, with Season 2 of The Wire and Season 3 of Atlanta: two series that had seemingly found perfection early on, but sacrificed it in pursuit of a larger purpose.

He took a hard left sonically, diving headfirst and expanding the sounds he had tiptoed in on Section.80. He employed a cadre of brilliant new-gen jazz musicians like Terrace Martin, Thundercat, Robert Glasper, and Flying Lotus, trusting them to craft a sound that was distinctive, unpredictable, and diasporic. They integrated jazz, blues, and funk, expertly tapping into both the commonalities and differences between multiple generations of Black music. Kendrick used his voice as an instrument in similar fashion, alternating between modern rapping, improvisational scatting, and spoken word poetry. The album was released in 2015, two years into the fledgling Black Lives Matter movement that was fueled by outrage over the unwarranted killings of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Rekia Boyd, among others. A sound so deeply steeped in Blackness was essential for the time, and in that manner, Kendrick and his collaborators delivered.

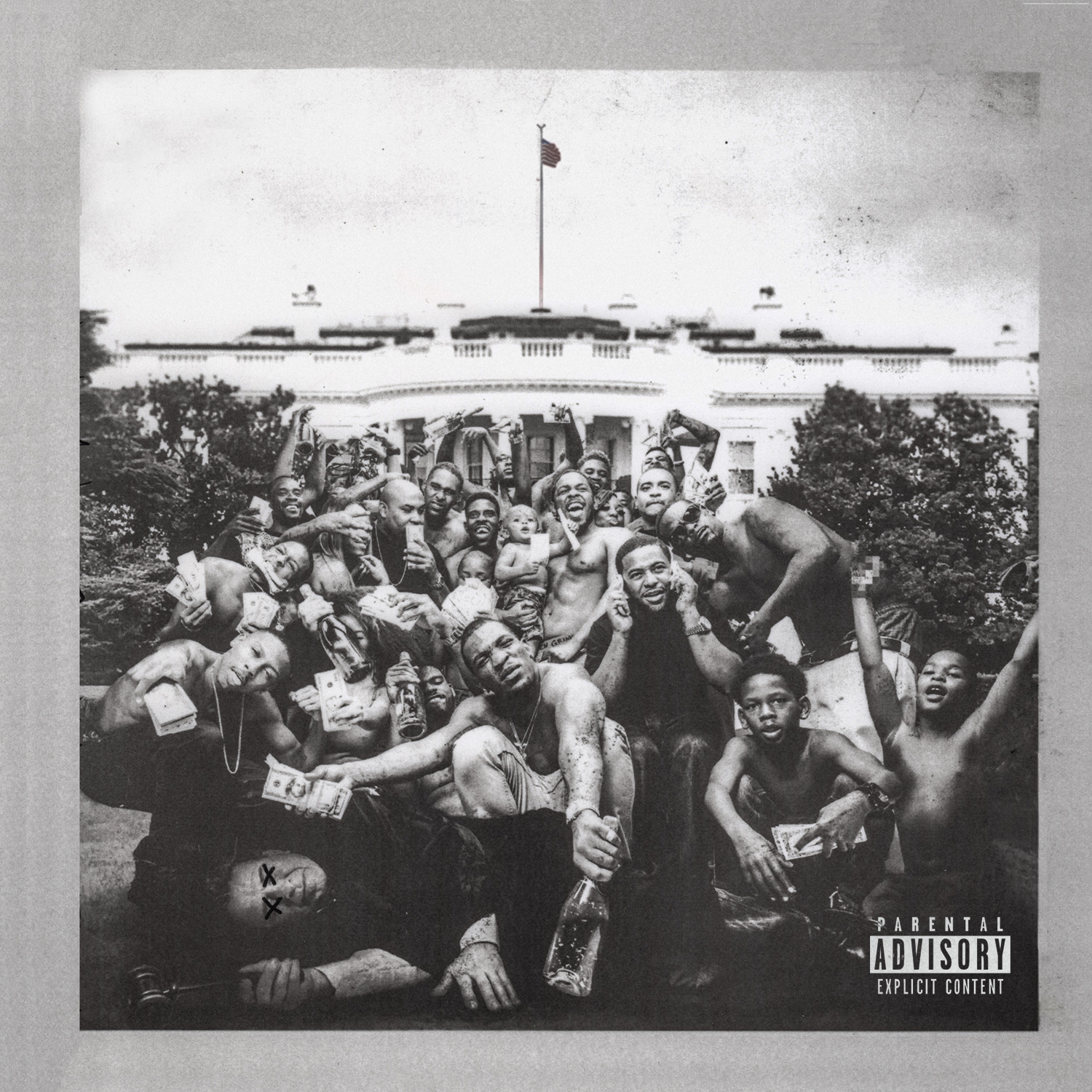

But Kendrick Lamar was a complicated voice for such conditions. "Alright" was literally a protest soundtrack, a Pharrell- and Sounwave-produced anthem that delivered hope and defiance that energized the fight against police brutality. The album's powerful cover art did the same, depicting a group of joyful, celebratory Black folks posing in front of the White House and on top of a judge who's clutching a gavel as his eyes are x'd out. But Kendrick was just as intentional about emphasizing that institutional racism isn't the only enemy. "The Blacker The Berry" starts as righteous indignation against the relentlessness of white supremacy, but ends with a callout of hypocrisy: "Why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street, when gang-banging make me kill a nigga Blacker than me?" Even now, listening to the song is invigorating and triggering all at once; I aggressively rap along in agreement to virtually every word, before cringing as he raps the final two bars. Putting police violence and gang violence on equal ground garnered backlash at the time. But the song is one of Kendrick's earliest examples on wax where he's willing to wade into unpopular politics to make a point he's passionate about.

Still, it's understandable that Kendrick Lamar was such a conflicted griot. He headed into GKMC feeling pressured about his leadership, and TPAB finds him doubtful about whether he can have the impact that he's so intent on making. Working to stop the gang violence in his hometown has always been a motif of his work, and becoming rich and famous doesn't mean that he's insulated from its effects. The self-love lead single "i" is performed on To Pimp A Butterfly as a skit, and when his simulated live performance is interrupted by a fight, he angrily pleads for the crowd to stop. "In 2015, niggas tired of playing victim dog!" he yells. "We ain't got time to waste time. … The judge make time, right?"

On the song's mirroring "u," Kendrick finds himself holed up in a hotel room, drunkenly beating himself up for focusing so much on changing the world that he's neglecting the people he personally knows. He vulnerably laments FaceTiming a close friend who was shot instead of visiting him in the hospital before he died, and blames himself for his younger sister getting pregnant as a teenager. "You preached in front of one-hundred-thousand, but never reached her," he guiltily raps at himself in the mirror. "I fuckin' tell, you fuckin' failure, you ain't no leader!" The album's coda finds him reaching out to his ancestors for guidance, visiting Nelson Mandela's prison cell in Robben Island, South Africa before a chilling conversation with a posthumous 2Pac, executed beautifully with a lost interview clip of the rap legend. Just as he appears to establish a connection with his fellow contradictory wordsmith, Pac disappears in the blink of an eye, leaving Kendrick to deal with his difficulties alone.

In the years since TPAB, Kendrick has continued to grapple with his leadership in different ways. Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers deliberately attempt to separate himself from the hagiography and deification altogether, despite wearing a messianic crown of thorns on the album's cover. He abandoned the pitch-perfect bop-to-substance symmetry of DAMN. for challenging soundbeds that harbored confessions of infidelity and sex addiction. He called on accused rapist Kodak Black to appear on multiple songs, almost as if to show that he saw himself in him in ways that most fans never would. "Kendrick made you think about it, but he is not your savior," he flatly stated on the album's second volume.

But since spring 2024, he's embraced his kingship completely. He may not be able to cure the world of all its ills on his own, but he can still run hip-hop and use that as a vehicle to do the rest. After sending early shots at Drake on TPAB’s "King Kunta" about his usage of cowriters, he exposed a vulnerability in Drake's slowly debilitating approval rates and went at him with a relentless suite of diss tracks. He psychoanalyzed Drake's character and blamed him for steering hip-hop in the direction of cynicism, materialism, and inauthenticity, accepting the role that was bestowed on Kendrick over a decade earlier as the culture's ombudsman.

While TPAB’s "How Much A Dollar Cost" finds him stingily refusing to give money to a homeless man who turns out to be God, he used his cultural and financial capital to host the Pop Out, a concert that platformed a dozen-plus West Coast rappers to a full house at Staples Center and Amazon Prime streamers at home. He used his Instagram page to release an untitled song where he insists that it's "time to watch the party die," bitterly admonishing hip-hop for its lack of conviction while looking up to Christian-forward rappers Lecrae and Dee-1. And after defiantly leaning into West Coast culture for his most bop-ready album yet with GNX, he gave a Super Bowl halftime performance that virtually ignored the hits in his catalog to deliver a message about America's rigid fences around Black expression — and hip-hop's ability to climb over them. His "tv off" lyric "fuck being rational, give 'em what they ask for" is largely attributed to Kendrick satisfying the public's desire for beef and bops, but it could also be expanded to mean that the people will embrace whatever Kendrick has to say. It's leadership rooted in confidence, experience, and insistence, all which would be impossible without the rollercoaster ride of To Pimp A Butterfly.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!