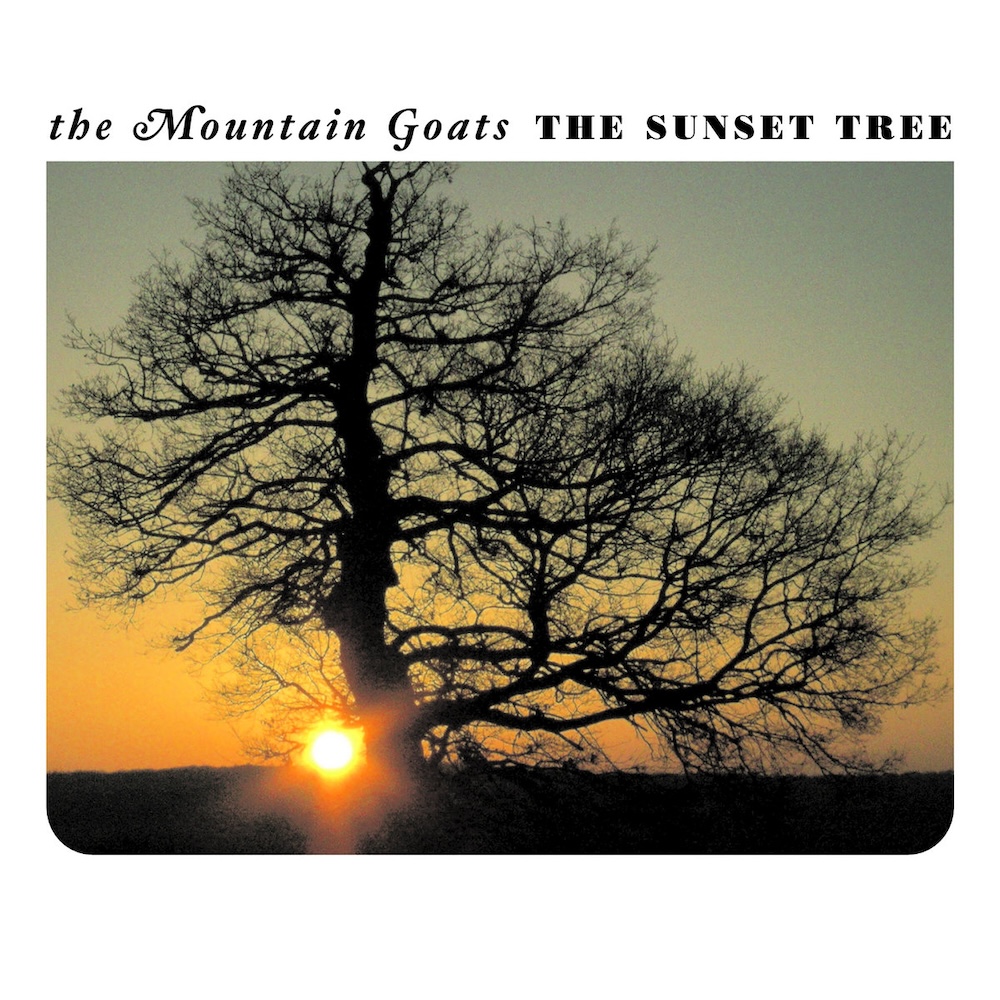

- 4AD

- 2005

One of the pro wrestlers is starstruck. I was not expecting this. It's 2015, and I'm in the Mid-Atlantic Sportatorium, a small room in a North Carolina strip mall that's entirely dedicated to independent wrestling shows. This particular one is being held by Chikara, a cartoonish American lucha libre company that will later shut down amidst abuse allegations against its owner. Some of the wrestlers on this card tonight will later make it to WWE or AEW. Most will not. One of the ones who will not is Argus, a rookie masked wrestler with a lizard-man character. On this night, Argus will lose to Hallowicked, a more experienced masked wrestler with a pumpkin-man character. But Argus wins something because he gets to meet John Darnielle. In the audience, Argus shyly approaches Darnielle, introduces himself, and then zips back to the locker room to grab his mask so that he can take a picture with the man. Even on this level, the lucha mask is sacrosanct. If Argus is going to get a photo with Darnielle, he will need the mask.

I'm here with John Darnielle on this evening because the Mountain Goats, Darnielle's indie-fixture band, have just recorded Beat The Champ, a concept album about professional wrestling. When Darnielle was a kid, back in the bloody and violent days of territorial wrestling, his stepfather would take him to see the matches at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles. That's what the album is about. Darnielle hasn't paid close attention to wrestling in decades, but the larger-than-life stories that he saw play out as a kid, the comforting clashes of good and evil, touched something deep inside him and continued to resonate as he got deep into adulthood. When I hear about this album, I pitch an idea for a feature story: I want to take Darnielle to his first wrestling show since his childhood. He's down, so we settle on this Chikara show, and we have a great night. I didn't count on any of the wrestlers being starstruck, but I should've known. I should've known because John Darnielle wrote "This Year."

"This Year" is a very specific song about very specific circumstances. It's part of a whole album about those circumstances. Darnielle wrote the songs on The Sunset Tree, the Mountain Goats album that will turn 20 Saturday, shortly after the death of his stepfather, the man who used to take him to those wrestling shows. In Darnielle's real life, the line between good and evil was harder to grasp. All through Darnielle's childhood, his stepfather was terribly abusive to his mother and to him. It's very hard to process the presence of an abusive parental figure in your life, and it's maybe even harder to process their absence when they die. The Sunset Tree covers a lot of ground, but much of the LP, including "This Year," focus on the moment when Darnielle was 17 and just starting to taste and imagine freedom while still being trapped with this dark force. "This Year" thrums with anger and determination and besieged optimism. It turns out that this feeling, conveyed so forcefully, applies to a whole lot of people going through a whole lot of things.

Later on, Argus tells me that "This Year" is his Mountain Goats song. It's the reason he was starstruck. When he started training to become a wrestler, Argus left his life behind and dedicated himself to an arcane, dangerous craft. It was a hard time. "This Year" became an anthem for him, a mantra: "I am gonna make it through this year, if it kills me!" I hope it turned out OK for him. That moment with Argus lived in my mind for the past decade, but I didn't keep up with his wrestling career, which is still going on some level now. He made it through the year, anyway. Lots of people made it through their rough years, and lots of people turn to "This Year" for help along the way. Until the equally feverish banger "No Children" became a TikTok dance a few years ago, "This Year" was the most popular Mountain Goats song, the one that they used to end most live shows even though they always delight in keeping their setlists unstable. Darnielle's specific writing, probably because of its specificity, became a transcendent gift to the world. For many people, "This Year" is the Mountain Goats song.

I love "This Year," but it is not my Mountain Goats song. My Mountain Goats song is "Hast Thou Considered The Tetrapod?," another one from The Sunset Tree. Does that one transcend its origin? Can people take its power and apply it to their own lives, even if their struggles are not the same as Darnielle's? I don't know. It's none of my business. "Tetrapod" matters to me because I lived that shit. On "Tetrapod," Darnielle remembers himself as a teenager who doesn't want to be where he is. He's always on eggshells at home, living in constant fear of upsetting a person who cannot wait to be upset. His only escape is in listening to music: "Alone in my room, I am the last of a lost civilization/ And I vanish into the dark and rise above my station." But the dark force awakens, and young Darnielle is violently yanked out of his trance: "Then I'm awake and I'm guarding my face, hoping you don't break my stereo/ Because it's the one thing that I couldn't live without/ And so I think about that, and then I sorta black out."

That was me. It was a lot of people. Maybe it was you, too. Sometimes, extremely specific songwriters can take you to places where you've never been, and you can find yourself identifying with situations that tell you new things about yourself. I love that -- granular idiosyncrasies that somehow become universal. Every once in a long while, though, an extremely specific songwriter might fuck around and hit you exactly where you live, to the point where you cannot believe that you are hearing your own experiences reflected back at you -- your own resentment and desperation and fear elevated and turned into art. That is a heavy experience. The Sunset Tree came out when I was 25 years old, just starting to understand and process the things that I didn't like about my own upbringing. The first time I heard "Tetrapod," it annihilated me, absolutely wiped me out. It did that again and again. I will have moments when I am simply unable to listen to "Tetrapod" for long stretches, and I will have moments when I need to hear it right away, immediately.

The Sunset Tree came along at an important time for the Mountain Goats. The band, which was really only just starting to become a band, was at a crossroads. John Darnielle had started the Mountain Goats as a mostly-solo project, braying his sharply written character sketches over acoustic guitar and recording them on a now-mythic boombox. After many years as a cult concern, Darnielle quit his day job and signed with 4AD, a real label. His friend Peter Hughes came aboard as a full-time bassist. The Mountain Goats' first 4AD album, 2002's Tallahassee, is a total fucking masterpiece, and it's the source of "No Children," the song that became the TikTok dance. In its moment, though, Tallahassee didn't find its audience -- not in the way that Darnielle hoped, anyway.

For the Mountain Goats' second 4AD album, 2004's We Shall All Be Healed, Darnielle tried something else. After all his years of writing about intricately imagined characters, Darnielle dug deep into a fraught period of his own life -- his time as a teenage meth addict, living in a Portland house full of teenage meth addicts. It's another masterpiece, and it didn't find its audience in its moment, either. Last week Darnielle reflected on the Sunset Tree moment in a Billboard piece from Stereogum friend Jason Lipshutz. In that time, Darnielle says, he was getting used to the idea that he would not be a professional musician, that the adventure was coming to an end. Darnielle was still living in Iowa -- he ultimately relocated to Durham soon afterward -- and The Sunset Tree was the last album of the Mountain Goats' three-record 4AD deal. He says, "I was like, 'I don’t really think that I’ll be doing this much longer.'"

When the Mountain Goats started making 4AD records, they switched their entire style up. In his lo-fi days, John Darnielle's desperate ferocity was one of the things that people loved about him. He wrote carefully and intricately, but he sounded like the songs were ripping their way out of his throat. Even when the songs were sad, as they often were, Darnielle sounded deliriously happy that he'd written them and that he was getting the chance to sing them. That's part of the magic that TikTok kids heard in "No Children" years later. The early 4AD records are still spare and feverish by nearly any standard, certainly compared to the music that the Mountain Goats make today. But those records are much, much richer and lusher than anything that Darnielle ever made on his own.

The Mountain Goats recorded The Sunset Tree with John Vanderslice, the same producer who did We Shall All Be Healed, and you can hear them figuring out how to make their songs grander and thicker -- a sense of discovery at work. Darnielle's friend and Extra Lens bandmate Franklin Bruno played piano on The Sunset Tree. The veteran avant-garde cellist Erik Friedlander is all over the record; he's the reason that "Dilaudid" sounds so vividly nightmarish. It's not like Darnielle had orchestras and choirs at his disposal, but I can get lost in the sonic textures of The Sunset Tree. It's one of the things that drew me to the album. Darnielle's harsh, declamatory delivery did not lend itself to any conventional notion of beauty, but he figured out how to make something beautiful out of it anyway.

In the aforementioned Billboard piece, Darnielle recalls the specific set of circumstances that led him to write his Sunset Tree songs. He says that he didn't write while touring in the band's early days but that he got to writing on the road after learning that his stepfather has died: "I was touring constantly then, and tour is an emotional pressure cooker -- especially if you sleep very badly on tour, which I do. If you deprive a person of sleep, their emotions come to the surface." Most of Darnielle's work had existed in opposition to the confessional singer-songwriter archetype, but that emotional pressure cooker took him to the place where he excavated old, scared, angry feelings and looked at the way that those feelings evolved as he escaped that caged-animal situation, often through self-destructive means. In a way, you could think of We Shall All Be Healed as the prologue to The Sunset Tree -- Darnielle dealing with his squalid and strung-out young-adult life before chronicling the thing that led him to that place. He would probably hate to see it framed this way, but I think of The Sunset Tree as a terribly brave and vulnerable record. I genuinely cannot imagine writing its equivalent for myself. Couldn't do it. Couldn't even think where to start.

Darnielle starts his version in a bargain-priced room on La Cienaga. On album opener "You Or Your Memory," we see a version of Darnielle shutting himself off from the world, thinking about embracing oblivion and ending his own life. We don't know how old he is. He could've been a baby, just out of his home, or he could've been a grown man, processing the loss of the person who pushed him right to the edge. It ultimately doesn't matter. That eggshell life sticks with you forever. A memory of a person can still torture you after the person is gone. The album plays out according to memory -- jagged and haphazard, jumping from one year to another. The moments don't end. You just keep reliving them.

Through much of The Sunset Tree, the moments that Darnielle relives are the ones where he was almost out the door, the ones where he could see some light, somewhere. He's met a girl, and she's got all the same demons as him. They're "twin high-maintenance machines," and they're good for each other and terrible for each other in all the familiar ways. Or maybe he's got a record player up in his room, and he can go up there and listen to dance music, learning that the volume knob is good for drowning out all the shouting from outside, or from inside. But his moments of freedom don't last, and he'll always have to come down and face his tormentor again. In one of the album's most affecting moments, he pictures his stepfather as a lion asleep in his car in the driveway, and he imagines himself reaching in, grabbing a single tooth, and doggedly holding on because he knows that he's dead if he lets go.

The songs are good. Darnielle's songs are almost always good, but The Sunset Tree is right in the sweet spot for me. It's got the raw, driving intensity of the early Mountain Goats records working in concert with the layered musical ideas that they'd explore over the next few decades -- the evolving musicality that would lead to Darnielle gradually adding more players to the Mountain Goats' ranks in the years ahead. When I go see the Mountain Goats live, which is still a profound experience, the Sunset Tree songs always get whoops of excitement from crowds, with good reason. It's my favorite Mountain Goats album. It's one of my favorite albums from anyone. But I don't listen to it very often. I have to be going through something. If I'm not, then the record puts me through something. I've written a lot of Anniversary posts for Stereogum over the years, and this one is a lot harder than most. I can't just casually listen to The Sunset Tree and talk about its context. It's not that kind of record. I've actually never written about The Sunset Tree at length before, despite dedicating god knows how many words to the Mountain Goats. It still feels too fresh, honestly.

Going back to The Sunset Tree after decades, one of the things that really hits me is the peaceful troika of ballads that ends the LP. On "Song For Dennis Brown," Darnielle imagines Kingston on the day that "all the coke in town" finally killed the reggae legend. It's just another day. The world doesn't shift dramatically. On the outside, "Song For Dennis Brown" doesn't have much to do with the rest of The Sunset Tree, but I hear the through-line. Darnielle's narrator knows that he'll find his own end eventually and that the rest of the world will keep functioning when that happens. From a certain perspective, that's a comforting thought. The thought returns on "Love Love Love," where he considers those who have done great harm to themselves and others: King Saul, Sonny Liston, Raskolnikov from Crime And Punishment, young Kurt Cobain. It's a fragmented meditation. Later on, Darnielle said that "Love Love Love" is about love as a potentially destructive force, not necessarily a good in itself. Darnielle's stepfather loved him, and he still hurt him. One does not negate the other.

The Sunset Tree ends with "Pale Green Things." That's the one where Darnielle is a kid, riding to the racetrack with his stepfather, savoring one of those beautiful little moments that you can still have with the people who fucked you up. Darnielle sings it in the second person, addressing it to his stepfather. When his stepfather dies, Darnielle sings, that's something he keeps remembering -- a morning at a racetrack, some plants pushing their way up through broken concrete. It could be a moment of forgiveness, if you want to hear it that way. Or it could be a wave of perhaps-unwanted compassion that comes crashing down on you when you're not expecting it. I hear different things in it every time, and all of them are beautiful.

That Billboard interview is part of a bigger story about the indie rock of 2005 -- the moment when new forms of internet visibility meant that relatively underground bands were starting to experience little moments of success, indicators that culture was changing around them. I guess I never thought of The Sunset Tree that way -- as the relative-terms hit that gave the Mountain Goats their final push into becoming an indie institution. My relationship to the record was too personal for me to hear it like that, but it changed Darnielle's life in ways that go far beyond just getting some shit off his chest: "The Sunset Tree occupies a unique position. It is the one that ends up telling me, 'This is your life’s work, for at least the next 20 years.' This record, uniquely at that time in our catalog, was speaking to a certain type of situation of abuse that people wanted to hear -- not in massive numbers, but in numbers that it reached gradually over time."

The Sunset Tree reached people. It reached me. It reached at least one young wrestler who was just starting his training. If you've read down this far, then maybe it reached you. I will take issue with one part of the Darnielle quote in that previous paragraph. At least for me, The Sunset Tree wasn't speaking to a situation that I wanted to hear. As good as these songs are, I almost never want to hear them. I put The Sunset Tree on when I need them. And when I need them, they're there.