- Parlophone/Virgin

- 2005

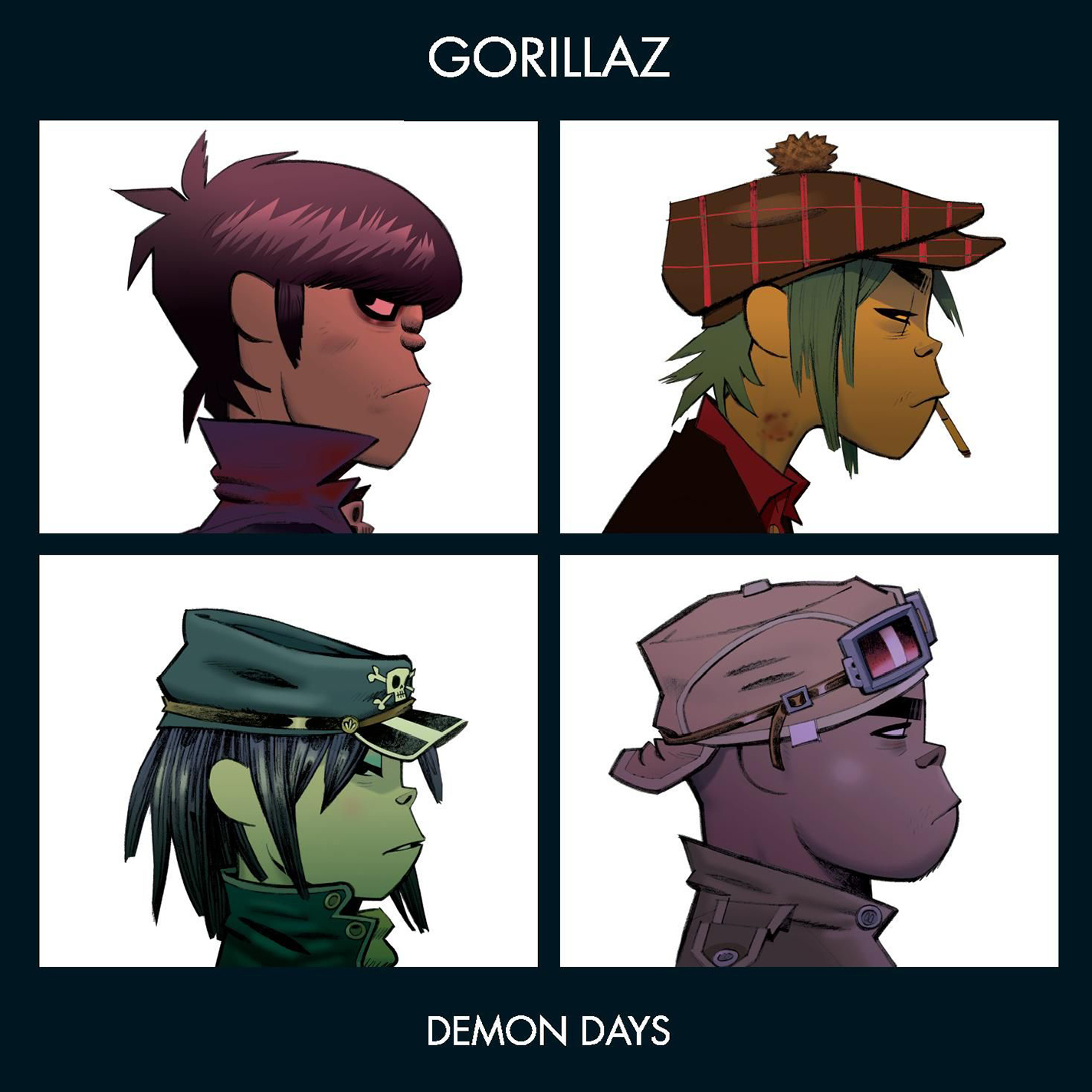

Demon Days wasn't supposed to happen. When Gorillaz' self-titled dropped in 2001, it was easy to imagine as a one-off: Famed Britpop frontman Damon Albarn bids farewell to the decade of his stardom by disappearing into a side project represented by cartoon characters dreamt up by Tank Girl artist Jamie Hewlett. Even after the success of Gorillaz, that sounded like the sort of story destined to be an oddity, a fun footnote in a musician's career. But when Demon Days arrived — 20 years ago this Sunday in Japan, a couple weeks later in the UK and US — it didn't just establish Gorillaz as an ongoing prospect. It laid groundwork for the argument that Albarn's seeming lark could become as important, or even more so, than the generation-defining work he'd already made with Blur.

After Gorillaz, Albarn returned to Blur for their once-maligned erstwhile finale Think Tank. Sonically, it was almost more akin to the interests that were driving Albarn's experimentation in Gorillaz than the majority of what Blur had released. It was clear Albarn's muse was elsewhere. In the meantime, he and Hewlett shopped the idea of a Gorillaz movie. After a disillusioning experience with the Hollywood machine, they decided to abandon the film but, after a long night of drinking, kicked around the idea of a sophomore album. "If you do it again, it's no longer a gimmick," Hewlett said upon the release of Demon Days. "And if it works, then we've proved a point."

For Gorillaz' second outing, Albarn's new approach bloomed. The prompt remained similar: few vestiges of rock music, instead replaced by hip-hop beats, squelching synths, and an array of guest collaborators joining Albarn's voice in the virtual world Hewlett continued to flesh out. The genre-agnosticism became both more sophisticated and expansive. Compared to the strung-out left turns of Gorillaz, Demon Days had a sweeping, unified aesthetic even as it veered from funky pop-rap hybrids to dubby choir refrains. To help him craft the more muscular, intricate sound, Albarn enlisted the then-ascendant young producer named Danger Mouse, fresh off his viral Beatles/Jay-Z mashup The Grey Album and still a year away from conquering the world with Gnarls Barkley's "Crazy."

While Gorillaz could feel like a voluminous sketchbook of zig-zagging adventures, Demon Days followed it with a fully realized world — a concept album in style and theme if not explicit narrative. One germ of inspiration came from a long train ride Albarn had taken from Beijing to Mongolia, through stretches of the Chinese countryside that had been left behind, its inhabitants abandoned and struggling. It dovetailed with global current events from the first half of the '00s and where Albarn saw things headed. "The whole album kind of tells the story of the night, staying up during the night," he explained. "But it's also an allegory. It's what we're living in basically, the world in a state of night."

In what would prove a magic trick rarely attained on later Gorillaz releases, Albarn peppered Demon Days with a greater array of more famous guests but orchestrated the album seamlessly. At times it felt like one long piece flowing together, even as "Kids With Guns" featured Neneh Cherry as a whisper augmenting Albarn and then "Dirty Harry" or "November Has Come" ceded centerstage to rappers like the Pharcyde's Bootie Brown or MF DOOM. He started to wrangle legendary figures far his senior — Ike Turner, Dennis Hopper. Somehow, though, the vision for Demon Days was so cohesive it all fit together.

This doesn't mean that the album didn't have its obvious standouts, of course. "Last Living Souls" opened the curtain for real with a piece of dub-synth-pop that seemed a far more crystallized descendent of rough drafts on Gorillaz. Album cuts like the celestial one-two finale "Don't Get Lost In Heaven" and the title track became mainstays in Gorillaz' live show. And while the debut boasted enduring hits like "Clint Eastwood," Demon Days had the truly ubiquitous singles. "Feel Good, Inc.," the shape-shifting and infectious team-up with De La Soul, was inescapable, as was the slithering dance-pop of "DARE," with the Happy Mondays' Shaun Ryder acting as a sort of hype man propelling the song to earworm immortality. Along with the gorgeous "El Mañana," the singles also came with increasingly ambitious videos, underlining the idea that Gorillaz weren't just here to stay but had become a real-deal big-budget endeavor.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

Throughout, Albarn refined Gorillaz' aesthetic, with certain shadowy-then-twinkling synth tones, rubbery basslines, and thudding beats becoming foundational. At the same time, he began to solidify the identity of the project beyond the initial premise of a virtual band playing on contemporary celebrity. His concerns broadened so that Gorillaz became his long funhouse mirror of a 21st century sliding out of control. It was on Demon Days where Gorillaz truly became a project about end times — set in a fantasy post-apocalypse as a way to discuss the various ways humans were wrecking the world around us. It was impossible to separate Demon Days from 9/11 and the wars that followed. Hopper's fable in "Fire Coming Out Of The Monkey's Head" arose from a simple idea Albarn had — what happens when all the oil is drained from the Earth? Though Demon Days was colored by societal and social ills, there it also began to look towards environmental collapse, a theme that would feature heavily on its successor.

The implausibility of Gorillaz remains fascinating. Here was a guy who'd already been a definitive artist in a very specific moment and milieu in his native England, turning his eye globally and coming up with a second act that ended up resonating with a whole new generation, whole other demographics. This was how many of us of a certain age really first came to know Albarn — it was through discovering Demon Days in high school that I was led back to that old Gorillaz thing I'd bought at 10 years old because I liked the "Clint Eastwood" video, and then back further to this other band called Blur. The darkened atmosphere and pop hooks alike could draw in American teenagers weathering the tumult of a new millennium that had arrived much more chaotically than hoped.

Though not universally lauded at the time, Demon Days’ legacy musically is arguably the broadest of anything Albarn has done. Arriving in the mid-'00s, Demon Days was one of those albums that taught us how to listen wider and wider, setting the stage for genre elision becoming the norm further into the '10s and '20s. The exact balance wouldn't ever quite be replicated. The end of Gorillaz Pt. 1, 2010's Plastic Beach, was already getting a little jumbled, and more recent collections have become a grab-bag of all kinds of the biggest names in music ever — apparently just because Albarn can, not because it makes sense. At the same time, latter-day retreads like 2023's Cracker Island can make you forget how seismic and weird and world-opening Gorillaz felt at that time, now that the borderlessness they espoused has become a more commonly accepted notion of how we consume and make art deep into the digital era.

It's easy to wonder if that makes Gorillaz, and specifically Demon Days, one of those "you had to be there" moments. In one retrospective published in 2017, Noisey once argued that Demon Days had actually proved prescient — that the political atmosphere allowed people to brush Albarn off in 2005, but that financial crises and chaotic world leaders had only served to show that Gorillaz' upside-down world was closely paralleling our own.

In its final moments, "Demon Days" talks about seeking oblivion through drugs and entertainment, with a final, surging plea carried on gospel melodies: "Pick yourself up, it's a brand new day… Turn yourself around into the sun." Twenty years on, it might be harder to embrace those parting words than ever. But amongst all the things that were never supposed to happen for Gorillaz, that might be the most striking. Damon Albarn, the man who had already written so profoundly about the trouble in navigating modern life, might have given us his most enduring and poignant attempt at making sense of a world crumbling around us while hiding behind a cartoon avatar, 15 years into his career, on an album nobody expected to exist.