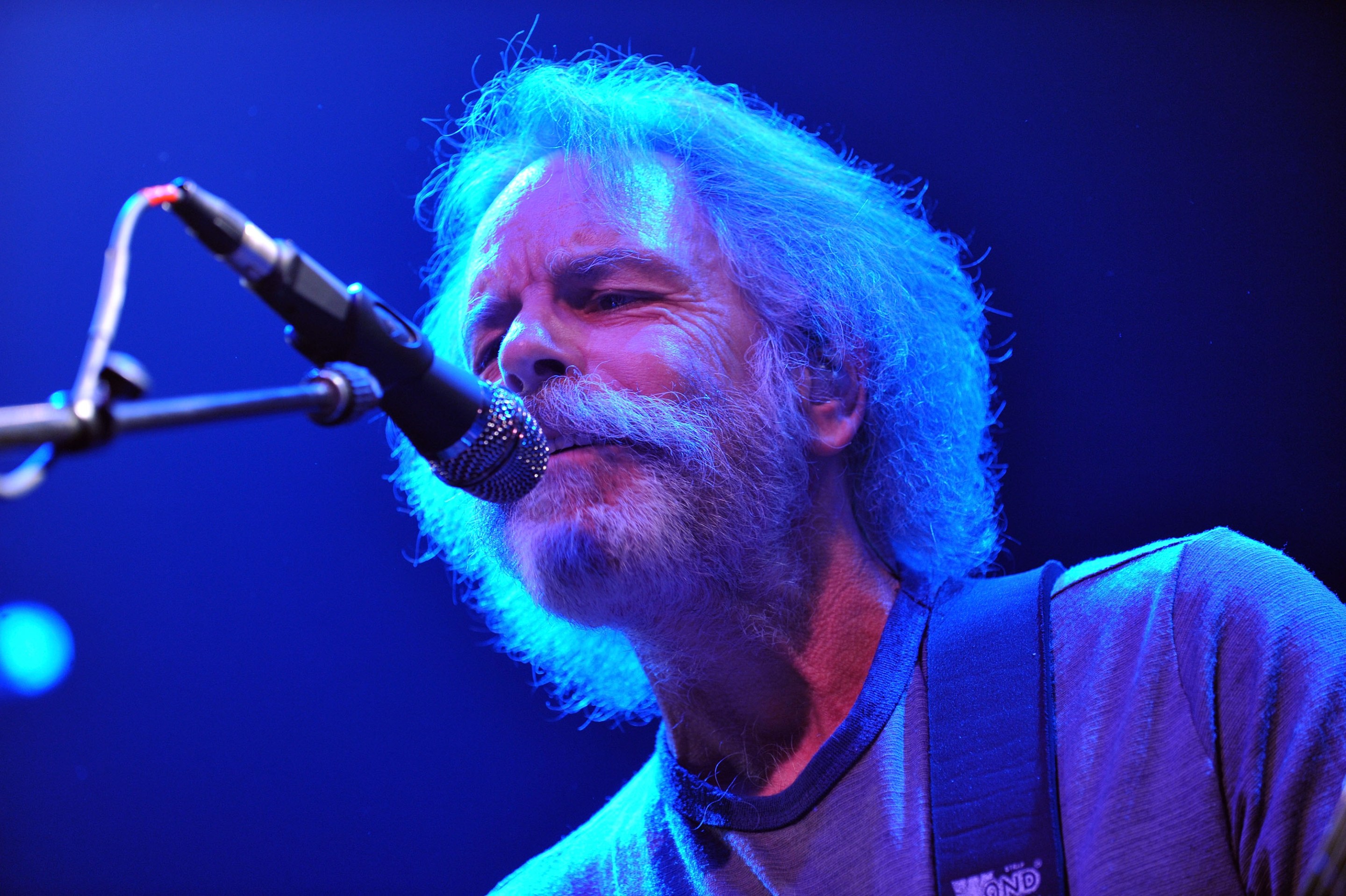

According to legend, back in 1968, Jerry Garcia and Phil Lesh fired Bob Weir and Pigpen from their positions in the Grateful Dead. Or maybe it was that Garcia and Lesh tried to fire Weir and Pig… or they asked the band's manager, Rock Scully, to fire those guys… anyway, long story short, the band failed to fire anybody. Pigpen died in 1973. Jerry passed in 1995. Lesh left us in 2024. Weir, meanwhile, was on stage at Golden Gate Park with Mickey Hart and John Mayer less than six months ago, celebrating 60 years of the Dead.

It's impossible to imagine what the Grateful Dead would have become if the guys in charge had successfully cut ties with Bobby way back in ‘68, but I feel confident saying it wouldn't have been a better band. Weir was surrounded by geniuses on three sides: Jerry over here on lead guitar, Lesh over there playing bass, and Robert Hunter off-site somewhere writing lyrics. Weir, meanwhile, was the youngest guy in the band, and the handsomest, and the one who played the upbeat "cowboy songs" in-between the Jerry numbers. Weir was the guy who shouted at people in the crowd who were acting like idiots, the guy who wore short-shorts on stage, the guy who did his best to keep shit together when the other guy couldn't. And even if he was never gonna compete with Jerry for solos, Weir was the one of the three greatest rhythm guitarists who ever lived. The other two are John Lennon and Keith Richards.

And somewhere along the way, those cowboy songs stopped being the interstitial palate cleansers between Jerry epics and became their own body of work. Over time, Weir's muse took him beyond the Dead – or forced him to work parallel to the Dead – hence his collaboration with lyricist John Perry Barlow, his work with Kingfish, with RatDog, with Wolf Bros. Weir's 1972 solo album, Ace, is literally full of songs that became classics once they made it into Dead setlists. Suddenly, the guy who once looked like the expendable junior partner turned into one of the band's most essential engines: a writer with his own cosmology, a singer with his own storms, and a rhythm guitarist playing chords that sounded like feedback, jazz, tumbleweed, surf rock, and telepathy.

It still doesn't compute that the man profiled in this 2020 Men's Health feature – chucking around a medicine ball, sinewed like barbed wire – is suddenly gone. But the music never stops. Fare thee well.

"Me And My Uncle"

"Me And My Uncle" is famously the most-performed song in the Grateful Dead archive. And I find this fact to be hilariously perfect, because there cannot be a single Dead fan ever – ever, anywhere, anyone, ever – whose favorite song was or is "Me And My Uncle," a cover of a tune written in 1964 by John Philips, of the Mamas And The Papas, who composed the whole thing while blacked-out drunk at a party also attended by Stephen Stills, Neil Young, and Judy Collins (who would be the first to record the song). It's a great story. Not a great song. But it's a great example of a type of Dead song, and specifically a type of Bob Weir song, i.e., cowboy songs, a class that also includes "New Minglewood Blues," "Mexicali Blues," and "Mama Tried," all of which are superior to "Muncle" in every respect except play count. So why is it included here? Because it's the most-performed song in the Grateful Dead archive. You can't not include it.

"Lazy Lightning/Supplication"

"Lazy Lightning" and "Supplication" are technically two songs, or at least that's how they first appear on the self-titled 1976 debut LP from Kingfish, a band in which Weir was briefly a member. ("Lazy Lightning" is the album's opener and "Supplication" is track two.) In any case, our list here technically goes to 11 as a result of this clerical choice, but you don't separate "Lazy Lightning" from "Supplication" any more than you would "Sunshine Daydream" from "Sugar Magnolia," or "Saint Of Circumstance" from "Lost Sailor." Soon after the release of Kingfish, Weir left that band, and a few months later, "Lazy Lightning/Supplication" made its first appearance in a Dead setlist. It's such a bold combo, all this chromatic tension and jittery movement; the jazz-fusion flashes of "Lazy Lightning" leading to the full-flight abandon of "Supplication."

"Looks Like Rain"

A controversial pick? We'll see how it's received here, but "Looks Like Rain" is historically a polarizing inclusion in the Dead catalog. It's an achingly beautiful love song (in some ways a precursor to the ubiquitous '80s power ballad) but it gets me bad every time it rears its pretty little head in a setlist. The lyrics are by John Perry Barlow – Weir's primary lyrical collaborator – written in 1972, probably about as cynically as Diane Warren was doing 'em a decade later. At the time, said Barlow:

"I secretly believed that ‘falling in love' was a conceit that people had made up in order to make themselves even more miserable for their perceived insufficiencies."

But wait:

"Twenty-one years later, I fell in love for the first time… After we'd been together almost a year, enjoying a relationship so radiant that others would gather around it like cats to a fireplace, we were at a Dead concert in Nassau Coliseum (of all grim places). Bobby started to sing ‘Looks Like Rain,' and I started singing it to her myself so that she would get all the words. About halfway through, I realized that I was getting all the words for the first time. I finally knew what the song was about."

I personally love Barlow's lyrics here, but it's Weir's delivery that carries them. The way he sings "But I'll still sing you love songs" with such gusto … and then follows with "written in the letters of your name" with such tenderness? It kills me, man. It wrecks me.

"Feel Like A Stranger"

It's fair to say that ‘80s Dead gets a little freaky, and none freakier than "Feel Like A Stranger," which was first performed on March 31, 1980, and included on the Go To Heaven LP, released the following month. It's part of an unofficial subcategory of Dead song that I refer to as "Sexy Bob Weir," a class that also includes "Estimated Prophet" and "Saint Of Circumstance" on one end, as well as "New Minglewood Blues" and "Samson And Delilah" on the other. "Stranger" is the very Sexiest Bob Weir, though; it has a louche, cruisy, nightclub vibe, and gets positively steamy when Weir and Brent Mydland are trading off on the outro section: "It's gonna be a long, long, crazy, crazy night/ Yeah, crazy night/ Silky, silky, crazy, crazy night." It opened many an ‘80s show like a curtain raising on a whole new Dead – slinkier, stranger, more synthetic – before melting into the thickest jam of the night.

"Truckin'"

Prior to "Touch Of Grey" in 1987, "Truckin'" was the Grateful Dead's highest-charting single, reaching #64 on Billboard's pop singles chart, the Hot 100, on Christmas Day 1971. It's a bizarre song to land as a hit, especially coming as it does off American Beauty, an album that includes "Box Of Rain," "Sugar Magnolia," and "Ripple," among other shoulda-been hits. (Surely the song's popularity was somehow boosted by the ubiquity of Robert Crumb's wholly unrelated "Keep On Truckin'" cartoon, but that doesn't make it less bizarre.) The song is a whirlwind, a magnificently detailed account of some of the band's many road misadventures. Dead house poet Robert Hunter sketches the life:

Sitting and staring out of the hotel window

Got a tip they're gonna kick the door in again

Like to get some sleep before I travel

But if you got a warrant, I guess you're gonna come in

According to legend, Hunter crafted some of the lyrics to deliberately tongue-tie Weir, to trip him up, to agitate and infuriate the band's rhythm guitarist, with whom Hunter had butted heads. Basically, it's a prank disguised as a verse. Try singing along: It's murder. Weir survived it just the same. (Weir's working relationship with Hunter, however, didn't make it.)

"The Music Never Stopped"

In a way, "The Music Never Stopped" is just as self-referential as "Truckin'," except it's the Dead on the road as seen through Barlow's lens rather than Hunter's. "There's a band out on the highway/ They're high-stepping into town…" Sure, it's postcard reportage, but there's something deeper that's aged well, especially as the Grateful Dead have evolved into Dead & Co., and Dark Star Orchestra, and JRAD... The music in question didn't belong to the Dead, and it didn't start when they rolled into town and stop when they left. It was always out there, on some frequency. Those guys were just tuning in and turning on.

"Let It Grow"

So technically "Let It Grow" is "Weather Report Suite: Part II," if you're looking for the song in its initial context. And "Weather Report Suite" is Weir's most ambitious work. It was included on 1973's Wake Of The Flood, serving as the LP's proggy, epic closer. The entire suite was performed only in '73 and '74, however. When the band returned from hiatus in '76, the only "Weather Report" piece they continued to play was "Let It Grow," the most propulsive of the three sections. There's a strong argument to be made that the complete "Weather Report Suite" is the correct inclusion on this list, and I don't disagree, because it's sprawling and meticulous and magnificent. However, I also… do kinda disagree? Because "Let It Grow" in isolation just goes so hard, and at this point, parts I and III feel a bit like vestigial curiosities. I suppose I could go either way here, but this is the way I'm going, so I gotta stand by it. My case is helped by the fact that "Let It Grow" is a live behemoth, almost a little intimidating if not scary. When the band hits the line "What shall we say, shall we call it by a name?" the whole crowd goes absolutely nuts, and when they hit "I AM," it's an actual climax that doesn't require any adornments on the front and back ends.

"Sugar Magnolia"

The Dead were never a studio band, never an album band, and that's true, except for when it's not, e.g., American Beauty, their second of two 1970 LPs (the first being Workingman's Dead, no slouch itself). I personally think American Beauty is a 10-out-of-10 classic that gets treated as a fluke because of the band's reputation. (And I think Wake Of The Flood is a 9.8-out-of-10 classic that gets downgraded or overlooked because of American Beauty's reputation as the only worthwhile Dead studio LP.) The first half of American Beauty feels like a statement, especially those first four songs: 1. "Box Of Rain" (Lesh vocal); 2. "Friend Of The Devil" (Jerry vocal); 3. "Sugar Magnolia" (Weir vocal); 4. "Operator" (Pig Pen vocal). That's four very distinct attacks across four perfect compositions, and it's such a rush. And "Sugar Mag" is the speediest bit of the buzz. The verse hits, the pre-chorus hits, the chorus hits, the bridge hits, and the coda fuckin' hits. The song, for me, just explodes in the fourth verse, when Weir sings, "She can dance a Cajun rhythm/ Jump like a Willy's in four-wheel drive." According to legend, that lyric was inserted into Hunter's original, post facto, by Weir, which is why Hunter stopped writing for Weir. A bit of passive-aggressive pissiness on behalf of all parties that changed the course of history for the better.

"Cassidy"

"Cassidy" is famously written for two people: Neal Cassady, the Beat icon, who died in 1968, and little baby Cassidy Law, who was born in 1972 to Eileen Law, the Dead's office manager. The first verse is explicitly for Cassidy ("Ah, child of countless trees/ Ah, child of boundless seas"), while the second is explicitly for Cassady ("Lost now on the country miles in his Cadillac"). And everywhere else, birth, death, and wide-open possibility are braided together. It's a complicated conceit and a devastating piece of music. In live versions, the band stretches the "flight of the seabirds" section into something propulsive and ecstatic. And when Weir reaches the denouement – "Fare thee well now/ Let your life proceed by its own design/ Nothing to tell now/ Let the words be yours, I'm done with mine" – it all comes together into something both mythic and human.

"The Other One"

If Jerry has "Dark Star," Bobby has "The Other One." The darker star. "The Other One" is barely even a song. It's a riff, a cadence, a fuse. It sounds like a threat until it makes good on the threat, and then it sounds like a riot, or a frantic attempt to contain a riot. It's the Dead at their most explosive and elastic. At the first snap of that opening tattoo, the band changes posture. Jerry is hanging back. Lesh is throwing grenades. The drums are a tribal stomp. The whole thing is basically a battering ram. You hear that riff start to churn, and just like that, it is fuckin' on. And for all the chaos, it never falls apart. The horses charge into the darkness, with Weir holding the reins the whole time.