November 9, 1991

- STAYED AT #1:2 Weeks

In The Alternative Number Ones, I'm reviewing every #1 single in the history of the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks/Alternative Songs, starting with the moment that the chart launched in 1988. This column is a companion piece to The Number Ones, and it's for members only. Thank you to everyone who's helping to keep Stereogum afloat.

In November 1991, Billboard ran a cover story on the marketing push behind Achtung Baby, the U2 album that was about to come out. The article, written entirely in music business-speak, contrasted the Achtung Baby rollout plan with the big, flashy campaigns for other big superstar records coming out around the same time, like Michael Jackson's Dangerous and 2 Legit 2 Quit, the latest from the newly renamed Hammer. (He'd just dropped the "MC" from his name; it would return later.) Unlike their fellow megastars, U2 weren't going for a full-on monocultural blitz. Instead, their label's efforts were "aimed squarely at the band's longstanding alternative base."

Given that U2 had already been a stadium act for years, one might wonder what the phrase "longstanding alternative base" might possibly mean. The answer, more or less, is "not Michael Jackson or Hammer fans." Island Records, U2's label, wanted fan excitement to push Achtung Baby, rather than any over-the-top ad campaign, even if "over-the-top ad campaign" was basically the ironic aesthetic that the band adapted. In the article, longtime U2 manager Paul McGuinness says, "There's nothing on this record except bass, guitar, and drums and U2... That's what always excited me about rock 'n' roll when I was a kid -- the idea of four guys onstage making an enormous noise."

Technically, Paul McGuinness was mostly accurate in his description of Achtung Baby. There's a little bit of keyboard action on the record, but there's nowhere near as much as you might assume. But U2, bored of their own images and of the idea of rock 'n' roll that they'd pumped into the universe, were in the midst of one of pop history's all-time great reinventions. They were making an enormous noise that sounded less and less like traditional rock 'n' roll, and maybe a little more like what you might've heard from Michael Jackson or Hammer around that time.

The Billboard article points out that Island Records didn't even push "The Fly," the first Achtung Baby single, to top-40 radio. That song became a huge pop hit elsewhere in the world. In the US, though, "The Fly" was the street single, the one for alternative stations only. It was loud and bright and discordant, and it sounded like it had been made on keyboards and drum machines, even if it wasn't. When Billboard ran that article, alternative rock was in a state of deep flux, and "The Fly" was in the second of its two weeks on the Billboard Modern Rock chart. Times were shifting, and U2 were shifting with them. Decades later, "The Fly" still sounds like a paradigm shift in progress.

Bono once said that "The Fly" was "the sound of four men chopping down the Joshua Tree." Conventional wisdom says that U2 finally drifted too far up their own ass when they started playing around with blues and Americana on 1989's Rattle And Hum. That conventional wisdom isn't quite wrong, though Rattle And Hum does have bangers, "Desire" not least among them. U2 paid attention to their own press, and they've largely gone back and forth between defending Rattle And Hum and admitting to its corny excesses. But that quote suggests that U2 didn't just want to move past Rattle And Hum. They wanted to tear down the entire image of themselves as ultra-sincere stadium-rock saviors.

Bono and the Edge wanted to tear it down, anyway. Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen Jr., the two fixtures of the band's rhythm section, weren't so sure. Mullen, in particular, was getting deeper and deeper into classic rock dynamics, and that's what he wanted to explore. But nobody was ever going to tell Edge to play the blues again. Edge was getting hung up on cutting-edge industrial music, and he wanted to figure out how to integrate that stuff into U2's music. Bono was on board. The other guys weren't. It made for a messy dynamic, and they had things to figure out. In late December 1989, U2 played a hometown show in Dublin, and Bono told the crowd that the band was about to disappear and "dream it all up again." One of the biggest bands of the '80s had to figure out how to be a band in the '90s. Unlike many of their peers, U2 succeeded at that. It wasn't easy.

After that Dublin show, U2, a tireless and prolific machine of a band, took an extended break from touring and recording. When they got back together, they played around with different ideas. In 1990, the band released an arch, drum-machine-damaged version of the old standard "Night And Day" for the Cole Porter tribute album Red Hot + Blue. That cover is fucking terrible, but Modern Rock radio was so starved for new U2 music that it went all the way to #2. (It's a 3.) That song didn't do any business in the rest of the world, but modern rock radio was still on board. The band's longstanding alternative base wasn't going anywhere.

Bono and the Edge also wrote a score for a Royal Shakespeare Company stage production of A Clockwork Orange. Critics hated that score, and so did Clockwork Orange writer Anthony Burgess. Eventually, U2 released one track, the clank-hum instrumental "Alex Descends Into Hell For A Bottle Of Milk/Korova 1," as a B-side to "The Fly." I think it's pretty good! At any rate, the rest of the soundtrack has never come out. Even if "Night And Day" and the Clockwork Orage score weren't exactly successful, they worked as rough drafts for some of the ideas that the band would bring to Achtung Baby.

Like plenty of people in the early '90s, U2 were inspired by the spectacle of the Berlin Wall coming down. When they got to work on new material, they brought back Daniel Lanois and Brian Eno, the team who's produced their albums The Unforgettable Fire and The Joshua Tree. Flood, who's been in this column for producing Depeche Mode, came on board as an engineer. The band left their families behind, going off to Berlin's Hansa Studio, near the rubble of the Wall. Eno had been a big part of the spaced-out, experimental records that David Bowie made in that studio in the late '70s, and U2 wanted some of that magic.

Later on, Brian Eno said that his big role on Achtung Baby was to help U2 stop sounding like U2. Eno and the band came up with a list of buzzwords to embrace and others to avoid. They were shooting for dark sexiness, and they wanted to get away from anything too earnest or righteous. One of the words that they wanted to stay away from was "rockist" -- pretty funny for one of history's most rockist-beloved bands. The term "poptimism" didn't exist yet, but that's basically what Bono and the Edge wanted for Achtung Baby.

The Berlin sessions were largely a disaster. The studio was a dump, the city was depressing, and the members of the band couldn't agree on anything. Bono and the Edge were into the brand-new rave-rock sounds coming out of the UK, and Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen basically wanted to make a rock record. Mullen thought of drum machines as an existential threat, and he wasn't into the idea of using loops in the band's music. The band at least considered breaking up before they all came together to improvise a song that'll eventually appear in this column. Once that clicked into place, they knew they were onto something.

U2 went back to Dublin, moved into a rented manor house together, and kept working. While the band cobbled ideas together on demo recordings -- some of which leaked, embarrassing them -- Brian Eno attempted to strip away the excesses that he heard. After tons of obsessive rewrites and re-records, U2 assembled what might be their best album. I think it's their best album, anyway. On Achtung Baby, I hear ideas flying in every direction. It's messy and jagged and sometimes awkward, but U2 still make those qualities work for them. They sound energized and reengaged, and the conceptual swings never overwhelm the songs -- not even on "The Fly," a lead single that mostly existed to reset expectations.

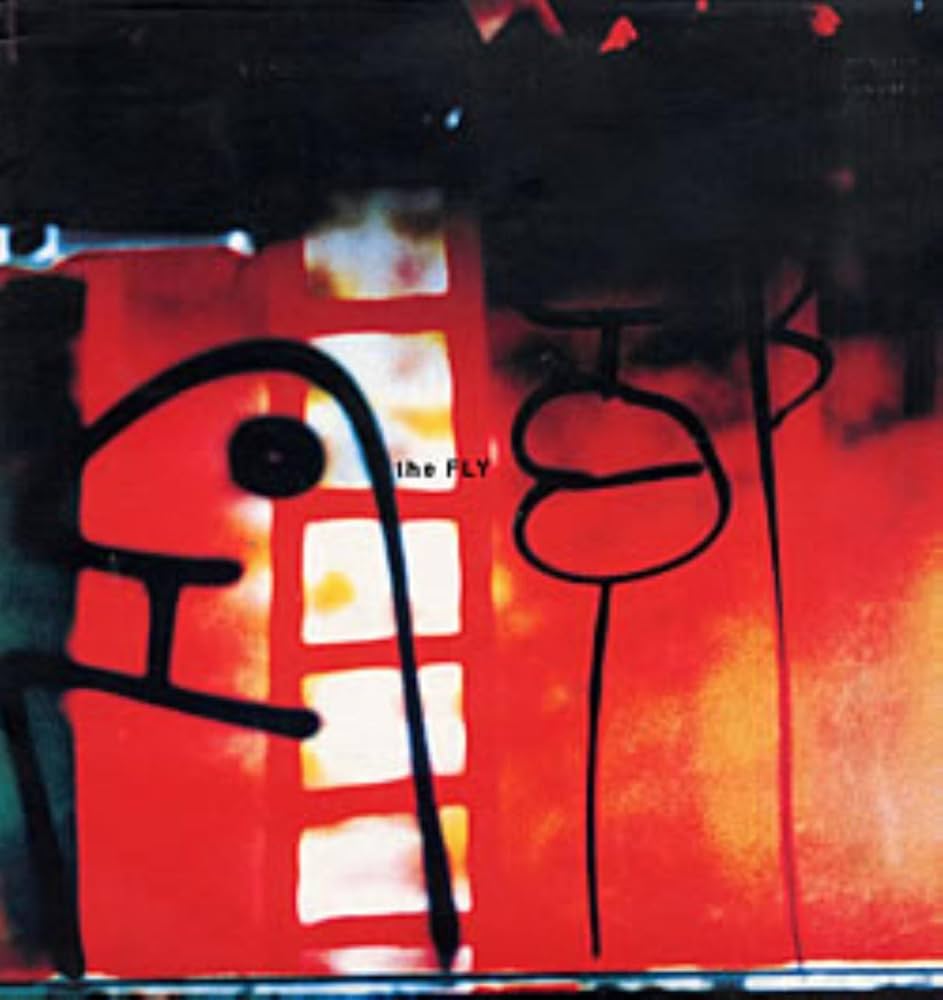

While working on "The Fly," Bono had to invent a whole new persona for himself. At some point, he got ahold of a set of giant black wraparound sunglasses, which reminded him of something out of a '70s blaxploitation flick. Bono would wear them to entertain everyone in the studio, and that led to a whole character, also known as the Fly. The Fly was a decadent leather-clad rock-star type, and he became a major part of U2's giant Zoo TV stadium tour in 1992. To accomplish that effect, Bono dyed his hair black. Maybe that song took him so far outside of his comfort zone that he had to become a completely different person to write it and sing it.

The Fly was supposed to be ridiculous. At one point, Bono told Rolling Stone, "The Fly needs to feel mega to feel normal." His lyrics for "The Fly" were influenced by Jenny Holzer, a conceptual text artist who would come up with meaningfully meaningless aphorisms that would then appear on plaques and posters. On the song, Bono comes up with his own little aphorisms, and he delivers them with deadpan authority: "Every artist is a cannibal, every poet is a thief/ All kill their inspiration and sing about the grief." When he ends that line by adding in that they do it "for love," it almost sounds like an afterthought.

Musically, "The Fly" reflects the Edge's growing love of industrial music. There are no drum machines on the track, and you can hear the sweaty groove of Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen playing together. But their sounds have been muffled and flattened, and the rhythm that they play is funky and percussive enough that you might trick yourself into thinking that you're hearing a looped breakbeat, at least underneath Mullen's fills. Edge had to do a whole lot of studio experimenting to find the sound of his damaged, serrated central riff. It's not the delay-drenched church-bell chime that he perfected in the '80s. Instead, it's a scraping honk that bounces around speaker channels, a rave klaxon taking organic shape.

"The Fly" is produced to sound like a dance track, even if it's a little too stompily muscular to qualify. The sounds cut in and out abruptly. Sometimes, they're layered enough to sound psychedelic. Sometimes, they're sharpened and streamlined to achieve a sense of total propulsion. Edge's solo sounds like a human voice, a wordless ululation. On the chorus, Bono sings that love shines like a burning star in an exaggeratedly honeyed high disco screech, and he had to come up with another whole new character to deliver that one. In the book U2 By U2, Bono calls that his "Fat Lady voice, which is really a kind of Jaggeresque, campy falsetto." Sure, Bono. Whatever it takes.

The track's sound could be a messy and ill-considered pileup, but the funny thing about "The Fly" is that it still works as literal stadium rock. The song might be an ecstatically meaningless jumble of ideas, but it moves, and U2 sell it with the otherworldly rock-star charisma that none of the younger indie-dance bands could approach. The only time I've ever seen U2 was at Chicago's Soldier Field in 2011, and they opened their set with "The Fly." It sounded fucking awesome in there.

U2 went intentionally low-key while promoting "The Fly." They made the song's video with directors Jon Klein and Ritchie Smyth in London and Dublin. Bono, dressed as his Fly character, wanders around streets, mugging at the camera while neon signs flash more goofy-ass bumper-sticker slogans: "watch more TV," "religion is a club," "taste is the enemy of art." It's presented less as a pop video and more as a declaration of a bold new direction and maybe also as a stealth preview of the Zoo TV tour. Around the world, however, "The Fly" registered as an actual pop hit. It followed "Desire" as the band's second #1 hit in the UK, where it ended the long 16-week reign of Bryan Adams' "(Everything I Do) I Do It For You." "The Fly" was also a #1 pop hit in Australia, Ireland, and a bunch of other countries. Around the world, people were willing to treat Bono's ironic rock-star character as an actual rock star, and Bono just rolled with it.

In America, nobody received "The Fly" as a pop song, and it only reached #61 on the Hot 100 -- way lower than the many Achtung Baby singles that would follow. But "The Fly" did hit #2 on the Mainstream Rock chart, and alternative radio loved it. The Madchester dance-rock music that informed "The Fly" was still all over modern rock radio at the time. Two weeks after it debuted on the Modern Rock chart "The Fly" was sitting at #1, while tons of other dance-rock hits -- from Primal Scream, Big Audio Dynamite II, Blur, Erasure, the Shamen, and INXS -- sat further down in the top 10.

Even if "The Fly" didn't hit here the way it did in the rest of the world, it set things up beautifully for the Achtung Baby release and for U2's greater future. When the album came out in November, the world was ready, and U2's longstanding alternative base was fully on-board. That would make a big difference over the years. A tidal surge was coming in the alt-rock realm, and another big, noisy, percussive song was about to reshuffle the deck. By going for radical reinvention at the exact moment that they did, U2 prevented themselves from becoming relics. They rode the zeitgeist into a tangled, unfamiliar future, and they kept the kind of credibility that they'd need in the years ahead. We'll see them in this column again soon.

GRADE: 9/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's the cover of "The Fly" that U2's buddy Gavin Friday recorded for a 2011 Achtung Baby tribute compilation that came with issues of Q magazine:

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's fan footage of Courtney Love and a late-period Hole lineup randomly covering "The Fly" at Brazil's SWU Festival in 2011:

(Hole will eventually appear in this column.)