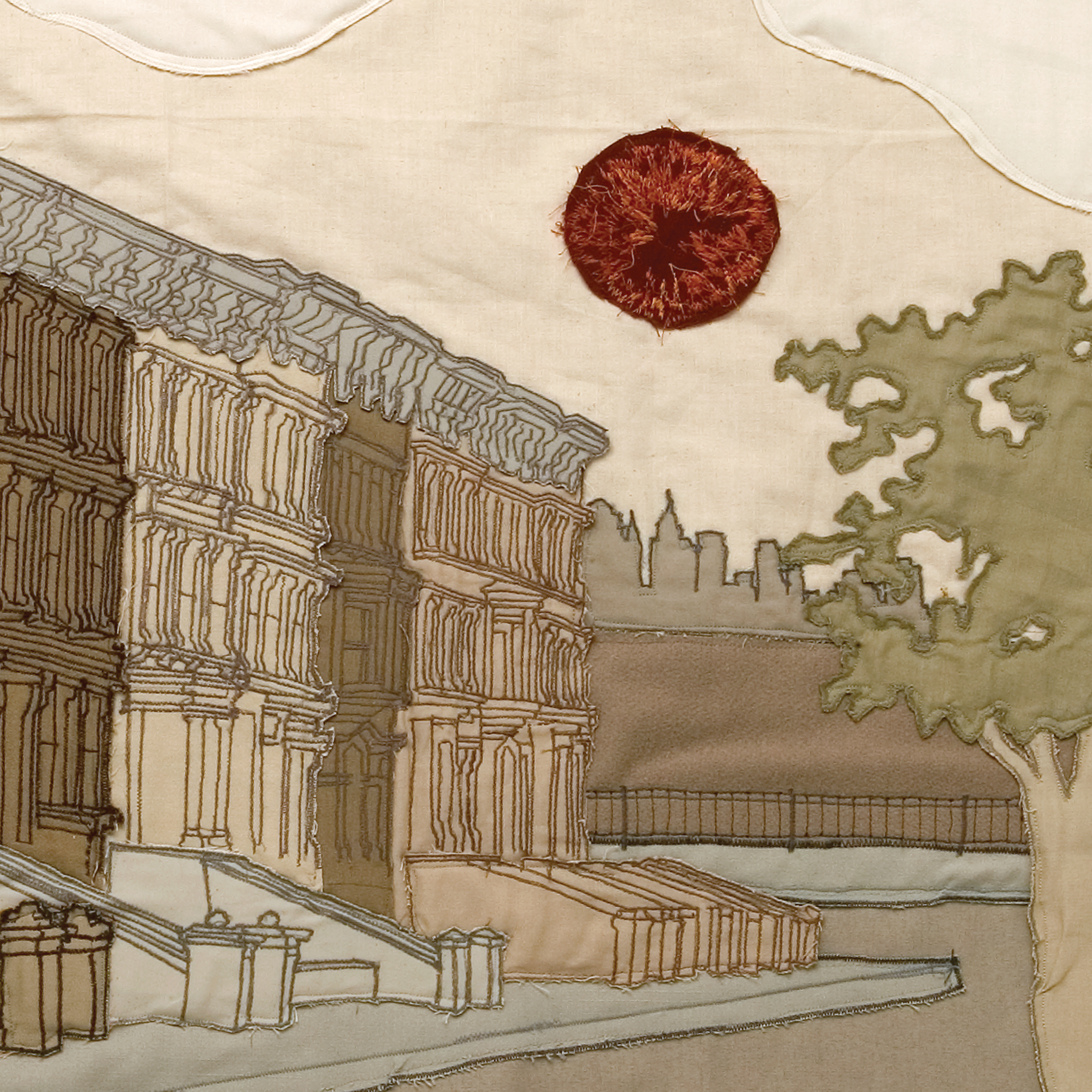

- Saddle Creek

- 2005

Bright Eyes records start by daring you to turn them off.

2002's Lifted opens with a guy and a girl driving around in the Omaha cold – just vérité nothingness until "The Big Picture" rounds out the eight-minute intro, and then the record really starts.

Every Bright Eyes record does some version of that, including Digital Ash In A Digital Urn, which greets you with trembling human breaths over some synth pads – more obstacle than song. The intention here, to quote writer Ian Cohen, is to chase off the squares.

I'm Wide Awake, It's Morning makes only a token effort at abiding by that tradition. We get a sip of water followed by a crystal clear monologue straight out of our hero's own mouth. It's a tight minute of that before bombing into both the ocean and one of the catchiest songs on the record – which doubles an open invitation to spend the next year asking him questions about Bob Dylan.

Conor Oberst would respectfully fend off those comparisons, but "At The Bottom Of Everything" gave newly interested late-night hosts and Times writers everything they needed.

I'm Wide Awake, It's Morning and its fraternal twin, Digital Ash In A Digital Urn, came out 20 years ago this Saturday. Both were released on the same day at what would prove to be the peak of the band's popularity. One catapulted Bright Eyes into the zeitgeist and remains by far their biggest record. The other was an experimental foray, a glitchy cult classic for the heads.

The most devout of Bright Eyes fans tend to keep I'm Wide Awake, It's Morning at arm's length. It's the record in which Oberst – erratic and messy by definition – grooved one down the middle. It's the record for the normies; the one you'll hear at Starbucks.

It's also great.

In 2005, Conor Oberst was fresh off playing benefit shows alongside R.E.M. and Bruce Springsteen in support of John Kerry's failed presidential run. The worm had fully turned on the Iraq War, which would nevertheless drag out into the following decade. Bright Eyes were on the brink, and Oberst commanded "a cult of hot, sullen Conorites who would gladly crawl through broken glass to lick his plectrum" – a fun little quote from Rob Sheffield's glowing Rolling Stone review.

Their previous record, Lifted, is all over the map, bound only by a ragtag drum corps and the feeling that we're among friends. We bounce from an emo-esque take on chamber-pop to a theatrical waltz to an acoustic guitar that sounds like it's on the other side of Omaha, all followed by the whiplash-inducing sequence of "Lover I Don't Have To Love" into "Bowl Of Oranges," both meticulously recorded but diametric in vibe. It resonated, setting the state for what came next.

I'm Wide Awake, It's Morning is a half-hour shorter and more contained in every way, at least until the very last minute. Oberst's vision was a '70s folk-rock record in the vein of Jackson Browne, which either means he was making a record specifically for me or he just wanted to bang out his little folk songs and save the freaky shit for Digital Ash.

But the idea that I'm Wide Awake is some sellout swing for the mainstream never made complete sense to me. That usually involves signing to a major label (they stayed on Saddle Creek), hiring a big producer (they self-produced both records), and writing radio-ready bangers (debatable I guess). Above all else, it's a collection of folk songs with anything superfluous cleared out of the way.

When it came time to promote it, Oberst went on Leno and played "When The President Talks To God," a roast of George W. Bush that isn't on either record. He dressed up as a cowboy.

I'm Wide Awake also arrived years before the stomp/clap indie folk of the Lumineers and Mumford And Sons, so it wasn't born into whatever twirly-mustache folk bubble you might associate with the 2000s. Its peers were "Float On" and Franz Ferdinand and the big-room indie rock of Arcade Fire.

Oberst was 24 and newly transplanted from Omaha to New York, stumbling about those city streets "like a midwestern transplant instead of a jaded hipster," to quote Chris Dahlen's Pitchfork review. In "Old Soul Song" we find him up against the barricades of a war protest, Mike Mogis' pedal steel sweeping us into the throng, and then later in a dark room with a friend developing photos that he hopes might hold some kind of truth.

In "Lua," set to a spartan sonic backdrop befitting the song's intimate subject matter, he's again walking about the city, this time with a companion whose troubles surpass even his own. Oberst has given us ample reason to worry about him over the years, but I always find it particularly brutal when he's worrying on behalf of someone else. I weep for Lua, even while darkly romanticizing the night Oberst describes in the song – one of those fucked-up stretches you end up looking back on fondly so long as you find your way out: "We might die from medication/ But we sure killed all the pain."

The best song on the record is "Landlocked Blues," the last of three in which Emmylou Harris loosely shadows the vocal melody like a lip reader mimicking her subject in real time. It's the voice of an angel just sort of winging it on God-given talent, and it's my favorite vocal harmony on any song ever. (Jim James on Track One makes that list, too.) The trumpet solo Nate Walcott plays toward the end is the sound of our flimsy post-9/11 patriotic togetherness giving way to everything that we have now.

I'm Wide Awake meanders between the personal and the political so artfully that you can miss it entirely if you want to. Like the "noise in the background of a televised war," the politics are at the edges, and yet it's easily the most political record the band ever made.

But it's also the record with "First Day Of My Life," a touchstone for millennial indie kids falling in love. If it played at your wedding, I hope you find your people in the comments.

Its conceit is simple and poignant – life began anew when I met you – and it straddles the indie/pop line as deftly as anything this side of "Skinny Love." And that's saying something considering it came out the same year as Death Cab's "I Will Follow You Into The Dark" and the exact same day as Plain White T's "Hey There Delilah." A banner year for the acoustic-guitar guy in your college dorm.

"First Day Of My Life" has been streamed 5x more than the next most popular Bright Eyes song, has been heavily synched, and is one of James Corden's Desert Island Discs – a real missed opportunity for Carpool Karaoke looking back.

I sort of believe Oberst could write "First Day Of My Life" over and over on command if he had the internal wiring of, say, Ed Sheeran. I asked him as much on a podcast I make called After The Deluge and he batted it away: "I wasn't trying to write some love song for the ages. It's hyper-sentimental and borderline corny, but it is what it is. I don't think I could just sit down and write that song over and over again. It happened very organically."

The liner notes for both records were written by JT LeRoy, an author du jour of the early 2000s who would soon get exposed in a strange catfishing-type scandal. The real-life writer, with whom Oberst spoke by phone at least once, was Laura Albert. The person behind LeRoy's public persona was a younger woman named Savannah Knoop, who would dress as a man to portray JT, accepting awards and hanging with the likes of Courtney Love, Winona Ryder, Billy Corgan, and even Bono. There's a documentary; it's wild.

Oberst is a blip in that saga, but the two had a long phone call that yielded the liner notes for the these records, and Conor would write a song about the whole ordeal a few years later on Cassadaga.

The liner notes tell the barely sensical story of a Big City writer dropped into a nation-state compound known as the Republic of Saddle Creek, where Overlord Oberst is seen mechanically churning out American folks songs – nothing else to see here. But off in some tucked-away corner, Mike Mogis shows LeRoy a secret machine that spins up digital tornados, couching Oberst as a mad man and these records weapons of terror. It's bizarre.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

Bright Eyes did separate tours for the two records, with separate backing bands and set lists. I'm Wide Awake came first: "It felt like we were the fucking Beatles," Oberst told me. "Everyone screamed, pictures, flashing cameras."

Next came the Digital Ash tour, with Saddle Creek labelmates the Faint opening and serving as backing band – seemingly a dream scenario for such a tour.

"Everyone left pissed," Oberst said. "They were like, 'This is the worst, what the fuck?' Ten years later people are like, 'Ohhhhh Digital Ash is my favorite,' and I'm like, 'Well I wish you would have come to the show because it sure didn't feel like that.'"

It's a point he's made about other Bright Eyes records over the years: confusion at first, followed by a slow crescendo of people telling him how much they adore 2011's The People's Key or whatever. (That one's about me). But Digital Ash is its own beast, and it's also the moment in which Bright Eyes formally became a band consisting of Oberst, Nate Walcott, and Mike Mogis, which is still the case today.

Mogis was miles beyond needing to prove himself by this time, having captured the feral teenage yearnings of Fevers And Mirrors and the kitchen-sink bonanza of Lifted, but Digital Ash is an album constructed of materials completely foreign to a luddite troubadour like Oberst. It lets Mogis run wild, and for the sonically adventurous among us who need more than just the sidewalk and the pigeons (not me), Digital Ash delivers. That said, earlier Bright Eyes favorites like "Neely O'Hara" and "Lover I Don't Have To Love" could have easily been on Digital Ash, so it didn't come out of nowhere.

The hard-panned hi-hat/snare taps of "Gold Mine Gutted" feel like a band deploying a shiny new tool. "Arc Of Time" takes the melodic percussion even further, and then "Take It Easy (Love Nothing)" dials it back just enough to remind you that Conor Oberst is still our main character.

Toward the end of the record the experimentation recedes and the whole thing starts to feel more familiar. Oberst thinks the title shaped perception, but he just thought it sounded cool: "[Digital Ash] is just a rock band with mad amounts of delay and effects on everything. It's not really an electronic record. There are only a couple songs that have computer-generated beats." It has me pondering the persuasive power of other albums that overtly told me what they were: Metamodern Sounds In Country Music and The Shape Of Punk To Come, I'm looking at you.

Nevertheless, we were fresh off the Postal Service and the Killers in 2005 and staring down the barrel of MGMT and LCD Soundsystem – a transition that would leave Digital Ash sounding far more like modern indie music than I'm Wide Awake does.

While Bright Eyes records typically start out slow, they end with an exclamation. In the case of Digital Ash, that's "Easy/Lucky/Free," a pulsing meditation that dares you to be optimistic even as it paints the bleakest of pictures. "Don't you weep" is a manifestation: Keep your head up while you can, for you will soon glitch out and die. It's the biggest song on Digital Ash, and it's beloved.

I'm Wide Awake ends with "Road To Joy," which flips the classic Ludwig Van Beethoven tune into chaotic folk-rock – an idea that somehow, against all odds, works.

"Road To Joy" is the actual best song on the record. (That was the Emmylou harmonies talking earlier.) It starts in an acoustic holding pattern before the Beethoven melody kicks in atop a thumping bass drum, which has the same mournful sentimentality as that "Landlocked" trumpet. The ensuing song is a pu pu platter of shit that's bad – an Oberstian speciality.

"I read the body count out of the paper/ and now it's written all over my face" are the words of a human living amid what feels like societal decay – relatable then, relatable now.But it's the next lines that fuck me up, especially when Oberst screams the second half – something he does sparingly up to this point on the record: "No one ever plans to sleep out in the gutter/ Sometimes that's just the most comfortable place."

Sit with that line for a second. Let all political complexities recede and spend a moment with the human calculus of it. You won't solve any problems doing that, but you might stumble upon some extra empathy. Can't hurt.

So when you're asked to fight a war that's over nothing

it's best to join the side that's gonna win

and no one's sure how all of this got started

but we're gonna make em goddamn certain how it's gonna end

And with that we lose our marbles and our minds, and a 2005 record that started as a refined exercise in restraint is now a goddamn mess. Like the war, like the country, like everything.

I could have been a famous singer

if I had someone else's voice

but failure's always sounded better

let's fuck it up boys, make some noise

Everything you need to know about Bright Eyes, these two records, and their whole career can be found in that last stanza. Their future, their past, all of it. Let's fuck it up boys, make some noise.