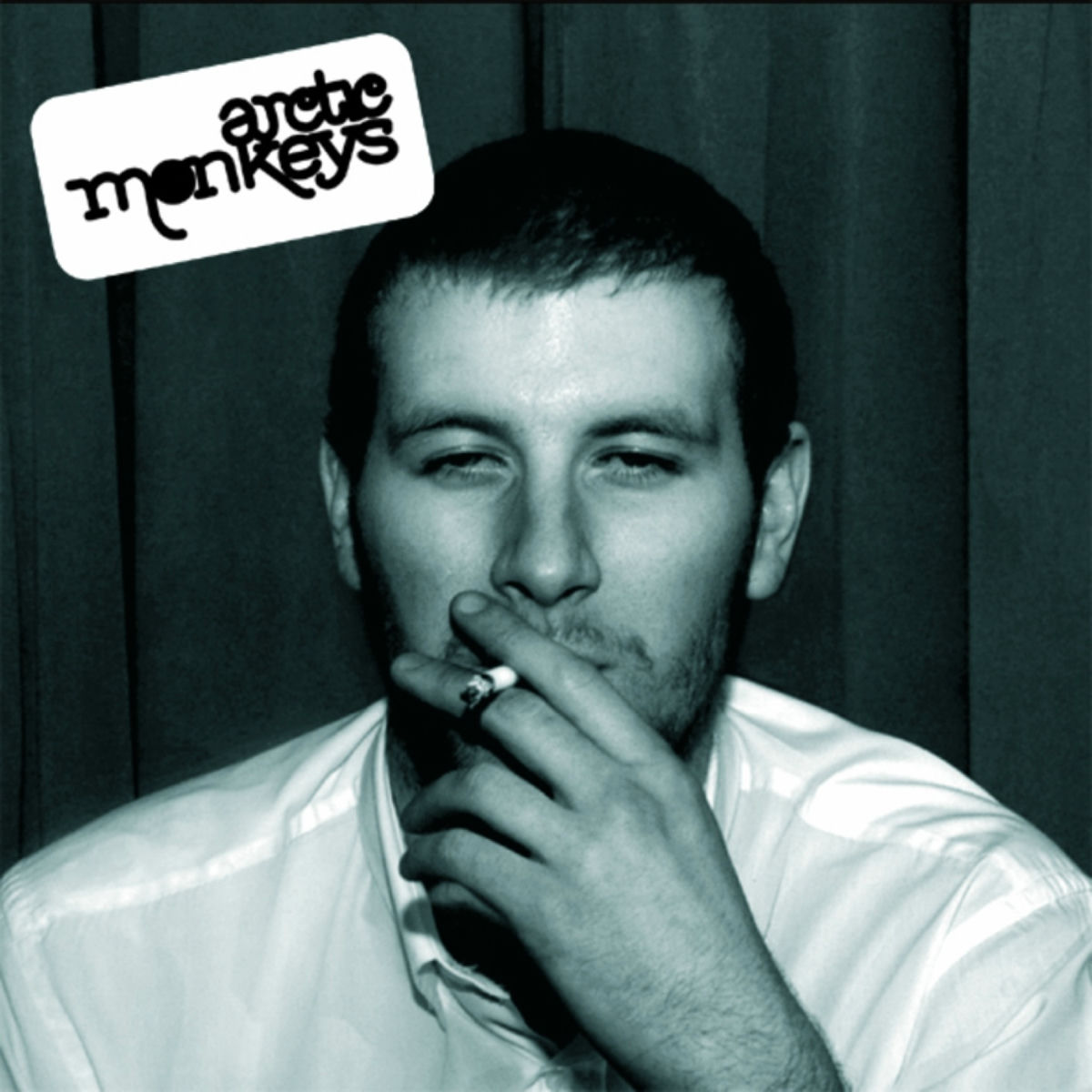

- Domino

- 2006

It's an old story. You've heard it before. It goes like this: There ain't no love here. No Montagues. No Capulets. Instead, it's banging tunes. DJ sets. Dirty dancefloors. Dreams of naughtiness. The people of the United Kingdom love those stories, those tales of grimy nightclubs and aggressive bouncers and unsuccessful hookup attempts and fights in chip shops and beer sloshed onto brand-new trainers. They love those tales to be rendered in the form of popular music, so that the tales might actually soundtrack the scenes that they depict. The British anti-glam storyteller tradition runs deep, and it's inextricable from the country's rock 'n' roll lineage. It keeps coming back, through the Kinks and Elvis Costello and Squeeze and the Specials and the Smiths and the Pet Shop Boys and Neneh Cherry and Pulp. But the story sounded different when it came from this kid.

The kid was new, but he and his friends had an old story. You've heard that story before, too. It goes like this: Young lads got bored out in their provincial city and started a band. They sang about the things that they saw happening all around them — the banging tunes, the DJ sets, the dirty dancefloors, the dreams of naughtiness. Their songs were messy and exciting and granular and noisy. The kids themselves were surly and foxy and funny. When the always-excitable British music press got ahold of them, they went absolutely fucking bucknuts, generating the kind of hype-frenzy that their American peers could only regard with absolute confusion. But the hype-frenzy worked, and these kids became real-deal rock stars in the last historical moment when kids like that could become real-deal rock stars.

In this particular iteration, the kids were were the Arctic Monkeys. As you have presumably already figured out from the headline of this blog post, that instantly canonized debut album was Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not, which celebrates its 20th anniversary today. Frontman Alex Turner turned 20 just a couple of weeks before Whatever People Say I Am came out, so the album is now pretty much exactly the same age as Turner was when it dropped. The line in question, about dirty dancefloors and dreams of naughtiness instead of Montagues and Capulets, comes from "I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor," a song that went straight to the top of the UK charts months before the album came out.

Once again, an old story felt new in this particular context. This time, it felt new because the hype-frenzy was faster and more overwhelming than anything that anyone had ever seen before. As someone who bought import copies of NME in the early '00s, I'd seen the UK music press go into overdriven delirium plenty of times before that, not just for the Strokes and the White Stripes but for Starsailor, ARE Weapons, the Music, the Datsuns, the Coral, the Von Bondies, the Thrills. Every month or so, the UK press grabbed some fresh-faced guitar band and made them out to be rock 'n' roll's newest saviors. In the case of the Arctic Monkeys, though, the UK press was merely playing catchup. MySpace had already done their job for them.

The music video for "I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor" wasn't a proper music video. It was a clip of the Arctic Monkeys playing live on a soundstage, looking as awkward and gangly as most people look when they're 19 or 20. Alex Turner opens the video by introducing both the band and the song and then by offering a word of advice: "Don't believe the hype." That's traditional, too. The hyped-up band isn't supposed to like the hype. They're supposed to stay grounded, to insist that they're just young lads in a band, that they're unflapped by all the noise surrounding them. That's part of the old story. But how could it not affect them? How are you supposed to sing about those dirty dancefloors when you'd get mobbed the second that you set foot on one of them?

The dirty dancefloors depicted on Whatever People Say, That's What I'm Not are the ones in the South Yorkshire industrial city of Sheffield. Those particular dirty dancefloors sure seem to inspire a lot of dramatic kitchen-sink songwriting. Fellow Sheffield band Pulp spent decades documenting the town's dirty dancefloors and dreams of naughtiness in lovingly louche detail. Considering the specificity of Arctic Monkeys' songwriting, you might think that Pulp would have to be a huge influence, but apparently not. A 2006 New York Times piece quotes Turner when he notes that Pulp's Different Class came out when he was nine years old and "more into climbing trees an' that." As it happens, Pulp broke up in 2002, the same year that the Arctic Monkeys got started, and their final pre-reunion album had a great song called "The Trees."

When Turner was climbing trees an' that, he was already close friends with the wildly gifted Arctic Monkeys drummer Matt Helders. They went to school and discovered music together. Deeper into childhood, they became tight with Andy Nicholson, the bassist that they kicked out of the band shortly after their debut album came out. The three of them started Arctic Monkeys for shits and giggles when all of them were about 15, and second guitarist Jamie Cook joined up shortly thereafter. They spent a year practicing in Turner's parents' garage, and their first show was opening for the Sound, another one of those UK hype bands, in 2003.

Turner wasn't into the idea of being a frontman at first, but songs started pouring out of him. He's got a particular kind of charisma. Back in the day, he didn't really sing. Instead, he drawled out his club-life observations in a sardonic, above-it-all sprechgesang patter that leaned heavily into his accent. The most immediate and obvious precedent for Turner's vocal style wasn't anyone in a rock band. It's the Streets mastermind Mike Skinner, who presented himself as a quasi-rap auteur and who used his own beats to tell stories about the dirty dancefloors of Birmingham, 90 miles south of Sheffield.

The Arctic Monkeys recorded a bunch of songs onto a demo that became known as Beneath The Boardwalk. They burned those songs onto CDs and passed them around to kids at their shows. Supposedly, the band didn't make their own site on MySpace, the social media network that was blowing up at the time. They didn't even know what MySpace was. Instead, fans established that MySpace page and uploaded those demos. That's the story, anyway. MySpace was in its infancy at the time, but it was already an important force in the kid-music space. I was in my mid-twenties when MySpace happened, and I didn't like the site. The design was too ugly, too clunky. I preferred Friendster, which means I was already left behind. In summer 2005, when Arctic Monkeys were building their legend in the UK, a friend showed me that this emo band called Fall Out Boy was doing insane internet numbers. The game was changing. A new generation was taking control.

The brand-new importance of MySpace meant that the Arctic Monkeys found an audience without the assistance of the always-hungry UK music press. Naturally, this made for a great press hook. The music press jumped on board in a hurry, and MySpace became a key component of the hype that we weren't supposed to believe. If you were so inclined, you could even posit the Arctic Monkeys as part of a new-generation wave that also came to include young rising UK stars like Amy Winehouse, Lily Allen, and Lady Sovereign, who all worked in different traditions but made their music feel like direct transmissions from the kids out there running around.

Of course, Arctic Monkeys also fit firmly into the NME-band mold, unlike those other artists that I just named. They were young and cute and brash and vaguely fashionable and male, and they made fun, literate, energetic guitar music that drew on various punk and post-punk influences. Arch, hedonistic bands like the Libertines and Franz Ferdinand owned the moment, and the Arctic Monkeys fit right into that. Between their lyrical approach and their sound, they were the Streets and the Strokes at the same time. This was a potent combination. Arctic Monkeys' rise is immortalized in their "Fake Tales Of San Francisco" video, which was shot and uploaded by a local fan with a video camera.

In the midst of their takeoff, the unsigned Arctic Monkeys played to a gigantic midday side-stage crowd at the 2005 Reading Festival and proved that the hype wasn't just hype, which of course led to more hype. The hype begat the bidding war, and the Arctic Monkeys signed with Domino, the same indie label that had just turned Franz Ferdinand into crossover stars. With Arctic Monkeys, Domino didn't even have to do much work. They were already there. The music press greeted them as the next Beatles, or at least the next Oasis. Before Whatever People Say I Am even came out, two different Arctic Monkeys singles shot straight to the top of the UK pop charts — "I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor" first, followed by "When The Sun Goes Down," an observational stomper about the sex workers outside the band's studios and the scummy-man types who patronized them.

The hype threatened to drown out the album itself. Watching it all unfold from across the pond was a little baffling. In its first week of UK release, Whatever People Say I Am sold hundreds of thousands of copies — a big deal in a country where you only have to move 300,000 units to go platinum. Whatever People Say I Am passed that threshold almost immediately before going platinum seven more times. The week that it came out, the NME immediately called it the fifth-best British album in history, putting it two spots above Different Class and four above Revolver.

Arctic Monkeys' publicists tried to get the same hype going over here, with real but limited success. On the Pazz & Jop poll, critics (some of them presumably British) voted Whatever People Say I Am the #7 album of 2006, behind Gnarls Barkley but above Clipse. It got a bit of alt-rock radio attention and went platinum, though it took 17 years to hit that milestone. American critics were too cynical to buy in whole-heartedly. The consensus I remember on the Arctic Monkeys at the time was that they were just one more British band, albeit a good one. Stereogum's own Scott Lapatine saw them at New York's tiny Mercury Lounge in 2005, but the only thing he remembers is that it was crowded.

Listening back two decades later, Whatever People Say I Am has aged awfully well. It's stormy and dizzy and cantankerous and idiosyncratic. Unlike so many of their UK buzz-band peers, Arctic Monkeys weren't going through the garage rock or dance-punk motions, and nobody would ever use the term "landfill indie" to describe them. Their skritchety guitars and off-kilter cadences had an all-elbows sense of immediacy. The rhythm section was fully locked-in, to the point where it's a little shocking that half of that team was gone a few months later. The songs, re-recorded from the demos, never feel too slick. Instead, the lurching, sozzled riffs have an unstable charge, as if the band knows that they have to pop all this shit off before they're absorbed into the big-time business of music.

Alex Turner's lyrical specificity, then as now, is what truly sets Whatever People Say I Am apart. He's angry and bored and hungry, lashing out at cops and bouncers and guys who can afford to buy drinks for girls and sometimes at those girls, too. He's already railing against everyone's idea of glamor, against the bands who lie about their time in faraway cities like New York and San Francisco, even though he's headed for real glamor himself. He's already lamenting a world where "there's only music so there's new ringtones," which makes me wonder how many ringtones the Arctic Monkeys sold. He delivers the line "you sexy little swine" with the exact correct combination of excitement, contempt, and detached irony.

Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not went on to pick up every honor that was available to a British band, from the Brit Awards to the Mercury Music Prize. Amidst all that attention, the band managed not to flame out. They took just a little more than a year to drop a pretty-great sophomore album, and they went on to become a polished and arena-ready hit machine and then to get bored of hits and to make the kind of self-serious art-pop that suggests that they weren't as ignorant of Pulp as they once pretended to be. (At the very least, the two bands shared an affinity for Scott Walker, the guy who produced that last Pulp album.) These days, Pulp are back and kicking ass, and the Arctic Monkeys are only just getting around to releasing their first song in years. Maybe it's generation-defining lyrically observational Sheffield alt-rock bands operate according to Highlander rules: There can be only one.

Over in the UK, the Arctic Monkeys an actual institution now. They've headlined Glastonbury three times, which tells you all you really need to know about their national-treasure status. In recent years, Alex Turner has talked about how he doesn't like playing songs from Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not anymore. He's never disowned the album, but he seems to think that it belongs to the world rather than to him. That makes sense. Honestly, that's what's good about the album. The Arctic Monkeys had to start somewhere, and they started with their wild young scrappiness on full display. They've done some extremely cool things in the intervening years, but that scrappiness is missed. It was special. It's the kind of quality that makes an old story feel new.