March 19, 1994

- STAYED AT #1:2 Weeks

In The Alternative Number Ones, I'm reviewing every #1 single in the history of the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks/Alternative Songs, starting with the moment that the chart launched in 1988. This column is a companion piece to The Number Ones, and it's for members only. Thank you to everyone who's helping to keep Stereogum afloat.

The Peabody Institute is officially part of Johns Hopkins University, but it's not on the Hopkins campus. Instead, Peabody is a little further south, in the Baltimore neighborhood known as Mount Vernon, right in the shadow of the Washington Monument. (I'm talking about our Washington Monument, not the Washington Monument.) Mount Vernon is right on one of Baltimore's main north-south corridors, but it always feels tiny and idyllic and old. It's got cobblestone streets and classical architecture. Akbar, a few blocks away from Peabody, is my absolute favorite Indian restaurant. That's still there, but I don't really know what else is in Mount Vernon these days. It used to have the cool record store and the cool bookstore/café. The rowhouse office for the Baltimore City Paper, the first publication that ever paid me to write, was a couple of blocks away. I have nothing but fond memories of Mount Vernon. I love that fucking place.

Tori Amos might feel differently. When she was a little kid, Amos was a classical piano prodigy, and she was the youngest person ever admitted to Peabody's preparatory division. I studied music at Peabody, too, but my experience wasn't like hers. I think my parents had me playing recorder there when I was about four -- the closest I ever came to learning to play an instrument. It was probably a summer camp or something. I remember that the building had very high, very pretty ceilings and that the light in there was gorgeous. That's all I got. At the time, I had no idea that Peabody was a prestigious classical institution. I was a kid, and it was a building where my parents sometimes took me. The name sounded funny -- pee-buddy. Nobody there had any expectations for me. I probably didn't know that Peabody was an important conservatory until I started reading magazine profiles of Tori Amos.

Peabody is central to the Tori Amos origin myth. The story goes that she was admitted to Peabody on full scholarship at five and kicked out at 11. She could play by hand, so she didn't like reading music, and maybe she was also more interested in rock 'n' roll than in the classical music that she was taught. If you ever have to write a magazine profile, a story like that is a gift from above -- a powerful illustration of your subject's unearthly talent and of her rebellious streak. It's too neat and broad a way to depict an actual human being's life, but when you've got a limited word count, you grab whatever symbolic significance you can reach. In this case, it gets across how this pretty red-haired lady with the piano got on the radio with her noisy song about how God needs to get laid.

When I first encountered the Tori Amos Peabody story, I didn't fully appreciate the weird trauma that must've come from it -- an august institution telling a little kid that she's doing things all wrong and she has to get the fuck out. My reaction was more like: Oh hell yeah! Baltimore, baby! We're doing big things! Forgive me. I'm the guy who gets misty-eyed watching old episodes of Homicide -- not because I'm seeing scenes where families learn that their loved ones have been murdered but because I'm like, "Damn, remember when Fells Point looked like that?"

Tori Amos wasn't born in Baltimore. She didn't start her recording career there. She doesn't live there now. (Neither do I, for that matter.) As far as I can tell, she doesn't claim the town. But the Baltimore connection prevents me from seeing Amos through the witchy earth-mother lens that seems to be the way the rest of the world sees her. I think she's just a cool lady who wrote some pretty songs about being horny and angry and confused. She might've been living out mythic fables as a small child, but that stuff happened in a building that was directly on my old bus route. That makes it hit different for me.

I was on board before I knew about the Baltimore connection. My Tori Amos aha moment was the 1992 VMAs. I didn't have cable, but I got a friend to tape that show, and I watched it over and over again. Amos didn't perform on that show, but her "Silent All These Years" video lost a bunch of awards to Nirvana and the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Annie Lennox. When they'd show the tiny clips of the nominees, I'd see those dreamy-jumpy images of Amos in the box, with that haunting music underneath her, and it captured my imagination. I got Little Earthquakes, Amos' 1992 solo debut, as part of one of those BMG Music Club eight CDs for a penny promotions when I was in eighth grade, and I read that lyric sheet over and over again. I probably understood half of it, but that half really got me. The record felt like something I wasn't supposed to like -- it definitely didn't have anything to do with the other stuff I loved at the time -- but that made it more mysterious and cool. Somehow, this thing found its way to me.

I didn't find Tori Amos through the radio. Maybe I heard "Silent All These Years" on the local alt-rock station once or twice, but it wasn't exactly burning up the airwaves. Amos has a big, rabid cult audience, and it seems like that audience has always been there. She was never a radio artist, really. But for a little while in the mid-'90s, the umbrella of alternative rock radio was wide enough that her sexually-frustrated-deity song "God" could be a #1 hit for a couple of weeks. In retrospect, that was a very cool historical moment. It's too bad we don't get things like that anymore.

Myra Ellen Amos was actually born in North Carolina, though her family didn't live there; they were just on a trip. Instead, Amos' family was based in Washington, DC. Her father worked as a Methodist preacher, and that definitely came to inform a whole lot of Amos' songs, "God" in particular. The family moved to Baltimore, the greatest city in America, when Amos was a small child. She taught herself to play piano when she was a toddler, and she wowed everyone around her by getting extremely good at the instrument extremely quickly. She went through the whole Peabody thing outlined above, and then her family moved to the DC suburb of Silver Spring, Maryland. In high school, Amos would play in piano clubs and gay bars, and her father would chaperone her. When Amos was in high school in 1979, she and her brother Michael entered a contest to write a new theme song for the Orioles, and they won. Amos recorded the single "Baltimore," and a few hundred vinyl copies were pressed up. So she did rep the city, at least in the very earliest moment of her career.

Hell yeah, baby! I'm proud to say I'm a Baltimorean, too! The Birds are the best! Brooks Robinson and Boog Powell retired a couple of years before Amos sang her "Baltimore" song, and Cal Ripken, Jr. was still down in the minors, a couple of years away from being called up. But that 1979 team had Jim Palmer and Eddie Murray and Ken Singleton and Rick Dempsey. They made it to the World Series that year, but they lost it to Willie Stargell's Pirates after blowing a 3-1 lead. Those were the good times. I was born in 1979, so I didn't get to actually watch that team except in a "my dad holding me up to the TV" type of scenario. But when you grow up in Baltimore, you live with the legends.

Anyway, William Donald Schaefer, best known to me as the mayor who jumped in the seal pool at the Aquarium that one time, gave Amos an official citation for her song. The song sounds like a '70s sitcom theme, and it fucking rocks. She should bring it back into rotation. Unfortunately, Amos did not continue to sing about the Orioles; I bet she could've had some serious things to say about Brady Anderson. After high school in the '80s, Amos moved to Los Angeles to try to make it in showbiz. She started going by the name Tori because, apparently, some guy told her she looked like a Torrey pine. What a weird thing to tell a girl.

I'm having fun here, but I'm also putting off writing this paragraph. This column is about to take a very dark turn; sorry in advance for the abrupt tonal shift. Out in LA, Amos got cast in a few commercials, and she kept playing in nightclubs. One night, she offered someone at one of her shows a ride home, and he kidnapped her and raped her at knifepoint. The trauma of that moment later shaped her music. She survived that experience, and she made something out of it. She sang about surviving the attack, forcing the world to grapple with the reality of that terrible moment, and then she became one of the first spokespeople for RAINN. She did what heroes do.

She also kept making music. Tori Amos played clubs as a solo act -- just voice and her piano. In the mid-'80s, however, she put together a band, and she gave it the honestly very funny name Y Kant Tori Read. This was apparently a reference to her being too impatient to read sheet music, but it's also just some goofy '80s shit. The drummer in Y Kant Tori Read was Matt Sorum, later of Guns N' Roses. (Sorum will eventually appear in this column as a member of Velvet Revolver.) People sometimes refer to Y Kant Tori Read as hair metal, but that's not quite right. It was more of a radio-ready '80s synth-rock situation even if Amos did have some very big hair. Y Kant Tori Read signed a six-album deal with Atlantic, but the project fell apart after their 1988 self-titled debut came out and flopped disastrously, only selling a few thousand copies. Amos has always seemed terribly embarrassed about Y Kant Tori Read, but I think their lead single "The Big Picture" is pretty sick.

After Y Kant Tori Read ended, Atlantic still had Tori Amos under contract for five more albums. She was crushed by her own perceived failure. She watched Tracy Chapman succeed by making heart-on-sleeve music and wondered why she wasn't trying to do something similar herself. Amos kept working, and she reshaped her sound into something much more idiosyncratic. She sang backup on a few other people's records. Under a pseudonym, she recorded a song called "A Distant Storm" for the Cynthia Rothrock martial-arts flick China O'Brien. She kept writing songs, and she turned in an early version of Little Earthquakes to Atlantic boss Doug Morris, who rejected it. She kept working on the songs until Morris understood what she was doing, and she moved to London to work with ex-Tears For Fears member Ian Stanley, who ultimately produced only a couple of tracks on the LP. One of those tracks was "Me And A Gun," a harrowing a cappella account of her rape. Finally, Little Earthquakes came out in January 1992 in the UK and a month later in the US.

Little Earthquakes was a top-20 album in the UK, which isn't that surprising. Nobody quite sounds like Tori Amos, but Kate Bush, someone who's already been in this column, is probably her closest comparison, thanks to the floridly impressionistic composition style and the mystical-feminine lyrical vibe. Bush was a superstar in the UK and a cult phenomenon in America. Little Earthquakes didn't quite put Amos on that UK-superstar level, but it was a pretty good start. In the US, the album got a bit of modern rock radio play, with "Silent All These Years" peaking at #22 and album opener "Crucify" peaking at #29.

Critics liked Little Earthquakes but never fully went all-in. In the 1992 Pazz & Jop poll, the record came in at #36, between Unrest's Imperial f.f.r.r. and the Black Crowes' The Southern Harmony And Musical Companion. Amos never made it back onto the Pazz & Jop top 40 after that. Horny writers loved to point out the way that she straddled her piano bench while playing live. In 1995, Amos appeared on the cover of Q with Björk and PJ Harvey -- an iconic image that I've seen reproduced on T-shirts for decades. But the magazine went with this as its coverline: "Hips Lips Tits Power." It's from a Silverfish song, but still, don't do that. At the time, most of the critical sphere didn't know how to write about women in rock without invoking the Women In Rock thing, and that reduced what most of them were actually doing. (Björk has been in this column as the leader of the Sugarcubes. As solo artists, however, both Björk and Harvey peaked at #2 -- Björk with "Human Behaviour" in 1993, Harvey with "Down By The Water" in 1995. They're both 10s.)

Little Earthquakes eventually racked up impressive American sales, but I don't think critical support or alt-rock radio had much to do with it. Instead, the album was a textbook slow-burn word-of-mouth success. It went gold in 1993, platinum in 1995, double platinum in 1999. Amos had a huge impact on the Lilith Fair generation that came up shortly after her, but Little Earthquakes didn't really fit into anything else that was happening when it came out. It's a singular record, and I think it's a full-on classic. With Little Earthquakes, everything that Tori Amos did up to that moment, from Peabody to Y Kant Tori Read, became origin-story footnote stuff. She had fully arrived, and she'd proven that she could get people interested in provocative, lightly discordant piano music. When it came time to record the follow-up album, Atlantic quickly gave up on trying to control Amos.

For 1994's Under The Pink, Tori Amos went off to Taos, New Mexico to record with most of the same musicians who'd played on Little Earthquakes. At least a couple of them, guitarist Steve Caton and prolific session percussionist Paulinho da Costa, had been working with Amos ever since Y Kant Tori Read. The producer of Under The Pink was Amos' boyfriend Eric Rosse, another classically trained pianist who'd already worked on a bunch of the Little Earthquakes songs. Amos also brought in the mighty Meters bassist George Porter Jr., and kindred spirit Trent Reznor came in to sing backup on her song "Past The Mission." (Reznor's band Nine Inch Nails will eventually appear in this column, though that won't happen for a while.) Under The Pink isn't quite as focused as Little Earthquakes, and it doesn't have quite as many moments that stop me in my tracks, but it's still a very strong record with some amazing songs. One of those songs is "Cornflake Girl." Going by streaming numbers, as well as the number of times I've heard it on TV shows like Beef and Yellowjackets, that's by far Amos' biggest song.

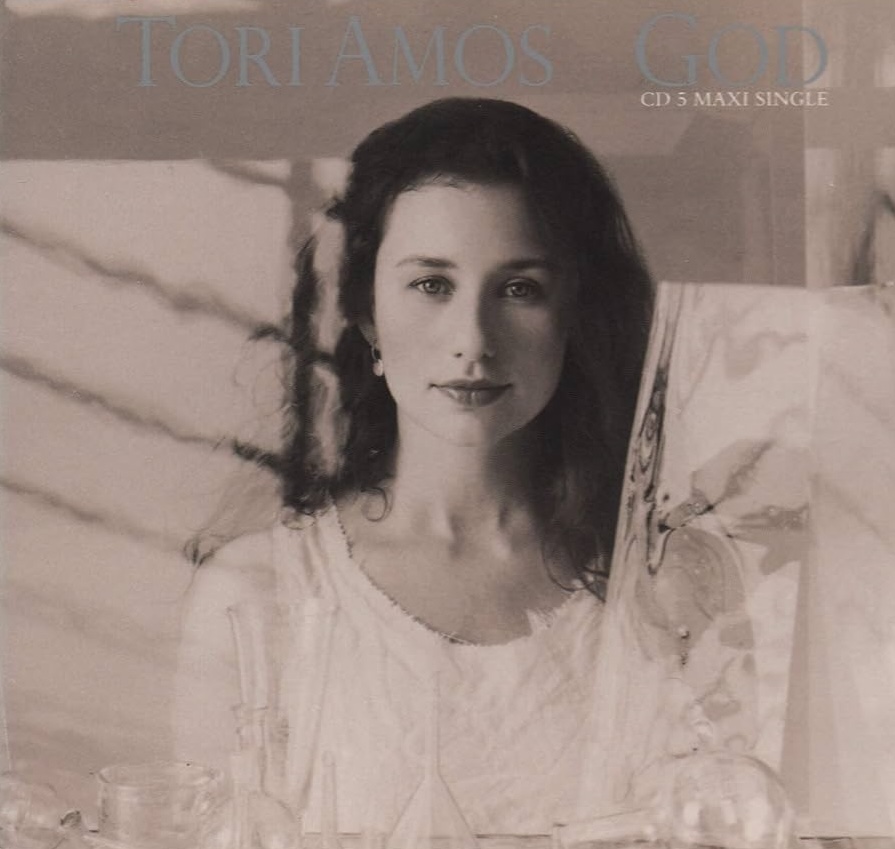

"Cornflake Girl" rips. Amos has said that the song was inspired by Possessing The Secret Of Joy, the Alice Walker book about female genital mutilation in Africa, but you wouldn't necessarily get that if you didn't read that in an interview. Without that information, "Cornflake Girl" is just a swirling, heavy, powerful piece of music -- art-pop done with force and muscle. The great session singer Merry Clayton bellows out backup vocals, and Amos truly hammers on her piano. The groove is a textbook case of what you can achieve when you've got someone from the Meters in your backing band. Everywhere except the US, "Cornflake Girl" was the lead single from Under The Pink. In the UK, that song became a #4 pop hit. In the US, however, "Cornflake Girl" was the second single. It never made the Hot 100, and it peaked at #12 on the Modern Rock chart. Instead, Atlantic decided to release "God" as the lead single in America. I wonder why.

"God" doesn't sound like an obvious smash. Really, no Tori Amos song, up to and including "Cornflake Girl," sounds like an obvious smash; she's not an obvious-smash type of artist. But "God" might be the first Tori Amos song that's actively off-putting. For one thing, it's noisy. Guitarist Steve Caton puts scratchy, abrasive scrapes and pings alongside his bluesy noodles. (Later on, he claimed that he recorded his bits while Amos was out shopping, and even she wasn't sure she liked his parts.) Caton's guitar noises dirty up a groove that's already plenty heavy and cranky. In the context of this column, I can't help but think of Suzanne Vega's "Blood Makes Noise," another track where a singer-songwriter messed around with a clanking, experimental backbeat. "God" sounds nervous and off-kilter, and even the prettiest parts never get a chance to settle in before the song interrupts itself again.

And then there's the subject matter. "God" is a happy piece of sacrilege. It's not quite the same as Amos' buddy Trent Reznor bleating that your god is dead and no one cares. It's not a sincere statement of atheism like XTC's "Dear God," either. Instead, it's Amos having fun with the idea that the deity is a repressed, undependable absent-father type. Amos sings that God sometimes don't come through and speculates that He needs a woman to look after Him. God makes pretty daisies, but He also lets witches burn. In her mind, God loves His golf clubs and his four-wheelers, and He might not even tell you beforehand if He lets the sky fall. She quotes a Proverbs line about how it's a bad idea to trust women: "Give not thy strength unto women nor thy ways to that which destroyeth kings." That Biblical passage is murmured so deep in the mix that you can barely make it out, but the intent is clear enough. God, as depicted in Christianity, is way too uptight, and that's the problem when a male entity has all the power. He can just crawl up His own ass and stay there.

When she was promoting Under The Pink, Amos told a story about calling her Methodist-pastor father, trying to find a Biblical passage that illustrates how Christianity has historically treated women. He tried to help, but he kept coming up with irrelevant quotes and then talking about how beautiful his quotes were. I think that tells us about Amos' relationship with her father more than with God. You have to grow up religious to write a song like "God," and songs like that usually work as repudiations of a writer's upbringing and, by extension, their parents. But Amos seemingly had a pretty good relationship with her parents even after she got famous. They weren't fanatical enough to get too mad about what she wrote, and she never got mad enough to try to piss them off. Instead, there's a level of playfulness at work on "God," even if the song gets a lot of its juice from transgression. Talking about "God" in interviews, Amos often used the word "cute."

Near my high school, there was this one ultra-Christian pizza place where they had Bible quotes written all over the walls and stacks of free Bibles that you could just take. The pizza was pretty good, so lots of kids would go there and kind of snicker over the decor. (If I remember right, there was a poster of a dog wearing sunglasses with a caption that said something like "the Lord is so bright I've gotta wear shades.") But I also knew some edgelordy goth kids who would take Bibles and then burn them in the parking lot, or at least talk about how they wanted to take Bibles and burn them in the parking lot. On "God," Amos strikes me as one of the kids giggling over the poster on the wall, not the ones burning the Bible in the parking lot.

I don't think "God" is one of Tori Amos' best songs, but I think it works. The beat rumbles and twinkles, and Amos sings with abandon even when you can hear a smirk in her voice. I like the way the stacked vocals seem to pull the track in multiple directions at once and how the choirs come in on the brief moments where everything else falls away. The melodies never quite resolve, and there's a bit of a Tom Waits junkyard avant-garde feeling to the anxiously piled-up production. Maybe Atlantic pushed "God" as the American single because it sounded more badass than most of Amos' tracks. Maybe they were after that stereotypical rocker-dude demographic, rather than the overwhelmingly female and queer audience that naturally gravitated toward Amos. You could theoretically headbang to "God," which is not the case with most of her songs, and the lyrics were guaranteed to get attention.

The "God" video got attention, too. Director Melodie McDaniel filmed Amos chasing different religious traditions' versions of ecstasy. She's in a Hindu temple with rats crawling over her, for instance, or in a Pentecostal church handling snakes. We see Hasidim wrapping leather straps around their arms. It's all pretty intense, as MTV spectacles go. Beavis and Butt-Head were taken aback. Atlantic's strategy must've at least partly worked. "God" is Tori Amos' only top-10 Modern Rock hit, and it became her first song to cross over to the Hot 100, where it peaked at #72. Under The Pink, like Little Earthquakes before it, ultimately went double platinum. In the UK, the album debuted at #1.

Tori Amos broke up with Eric Rosse, and she started producing herself when she followed Under The Pink with 1996's Boys For Pele. She recorded most of the album in an Irish church, and it's a bit more psychedelic than anything else she'd made up to that point. Boys For Pele went platinum, and the twitchy lead single "Caught A Lite Sneeze" peaked at #12 on the Modern Rock chart. Once again, a Tori Amos record did pretty well despite having very little to do with anything else that was happening in popular music at the moment. Boys For Pele also had "Professional Widow," a song that's widely rumored to be a Courtney Love diss track. (Love's band Hole will eventually appear in this column.) "Professional Widow" had quite an afterlife. The great house producer Armand Van Helden reworked "Professional Widow," transforming it into a hammering dance banger, and his remix became a #1 pop hit in the UK. It turns out that Tori Amos makes a great dance diva, even if she never meant to be one.

"Spark," the lead single from Tori Amos' 1998 album From The Choirgirl Hotel, was the last time that she had a song on the Modern Rock chart. (Like "Caught A Lite Sneeze" before it, "Spark" peaked at #12.) In a way, it's amazing that Amos was able to maintain a presence on alt-rock radio even as we got into the post-grunge era. She was still operating on her own wavelength, and people were still meeting her where she lived. "Spark," incidentally, is a really good song. It's also Amos' biggest-ever Hot 100 hit, reaching #49. From The Choirgirl Hotel and Amos' 1999 half-live, half-studio double album To Venus And Back both went platinum.

After multiple miscarriages, Tori Amos and her sound engineer husband Mark Hawley finally became parents in 2000. In 2001, Amos released Strange Little Girls, a concept album where she played haunted, stripped-down covers of a bunch of ultra-male songs -- Eminem's "'97 Bonnie And Clyde," Slayer's "Raining Blood," the Beatles' "Happiness Is A Warm Gun." I thought that album was cool, but it was the last Tori Amos album that really reached me. That didn't matter. Amos still has an audience that'll follow her to the ends of the earth. She's continued to move from one major-label deal to the next, and she's amassed a pretty huge discography. Every once in a while, I'll check out a new Tori Amos record when it comes out, and I'll be like, "Damn, this is good, I need to pay more attention to Tori Amos," and then I forget about it again.

Earlier this year, Tori Amos published a children's book, Tori And The Muses, and she surprise-released a soundtrack album for that book. On her book tour, she came to the church where I went to kindergarten -- another Baltimore place with architecture that made a deep impression on my forming brain. I love the idea that Tori Amos, who has basically nothing in common with me but who probably had a lot of formative experiences in the same buildings that I did, is still out there, pulling people into her world. She never became one of the titans of alt-rock radio in the '90s, but she had her moment, and then she kept going. I salute her.

GRADE: 8/10

BONUS BEATS: Before Armand Van Helden's "Professional Widow" remix became Tori Amos' biggest UK hit, she got Detroit techno pioneer Carl Craig to do a couple of very cool extended "God" remixes. Raver Tori strikes again! Here's Craig's Rainforest Resort Mix: