October 16, 1993

- STAYED AT #1:3 Weeks

In The Alternative Number Ones, I'm reviewing every #1 single in the history of the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks/Alternative Songs, starting with the moment that the chart launched in 1988. This column is a companion piece to The Number Ones, and it's for members only. Thank you to everyone who's helping to keep Stereogum afloat.

Nobody in rock history has ever had to make an album quite like In Utero before. The circumstances that led to In Utero are entirely unique. It's hard enough to follow a universally lauded breakthrough album. But when you're trying to follow a universally lauded breakthrough album that also marked a momentous cultural sea change? When you've suddenly yanked yourselves out of obscurity and into the pantheon? When your own ideals mean that you can never be comfortable in that new position? When all of your destitute idols suddenly have major-label deals and you're the reason? When you think that most of the other bands who have followed you into stardom are lame? When you've come to stand in for various different generational buzzwords that mean nothing to you? When you also have so much other bullshit happening in your life? Well, brother, that's a lot.

Here are some things that happened to Kurt Cobain in the two years between the releases of Nevermind and In Utero: He got rich. He got famous. He married another person who was in the process of getting rich and famous. He became a father, and then the authorities briefly took his baby away because of press comments about his and his wife's drug use. His occasional heroin use ballooned into full-on addiction. His chronic stomach pain and depression got worse. He redid his band's paperwork so that he'd get most of the royalties, and in the process, he pissed off his two bandmates in a major way. How does anyone create art under those circumstances? How is it even possible?

When Nirvana made Nevermind, Kurt Cobain was a normal person, more or less. He was a tremendous, earthshaking talent, and some people probably realized that, but most didn't. He was young and pretty and broke, and he could walk through any public space unmolested. When Nirvana made In Utero, Cobain was living an insane, unstable, unsustainable life. He was unhappy in ways that most of us will fortunately never be able to comprehend. Also, he was about to die. Whether or not Cobain knew it at the time, In Utero was to be his artistic last will and testament -- the final studio album that he would ever make. About seven months after its release, he blew his own head off.

When the surviving members of Nirvana look back at that time in their lives, the phrase "biggest band in the world" gets thrown around a lot. I'm sure it felt like they were the biggest band in the world. In terms of raw impact, that's probably what they were. But by 1993, Pearl Jam, their immediate contemporaries, were outselling them by almost two-to-one. Nirvana toured arenas as a headlining act for the first time after In Utero was already out. They weren't the biggest, and I'm sure there was some concern that they were about to fall off commercially, that Nevermind was a one-off cultural blip that could never be repeated. Probably, that's what Cobain wanted. Advance press on In Utero was all about how the band had intentionally made something so abrasive and off-putting that their label was scared to release it -- which, paradoxically enough, made for amazing hype.

In retrospect, it's incredible that Nirvana even made another album after Nevermind. If Kurt Cobain had gone off to live in a cabin somewhere, if he never made music again, it would've made perfect sense. (For him and maybe for us, it would've been better than what happened.) Plenty of great bands have fallen apart because of pressures that would've barely registered on circa-1993 Nirvana. Soon after the release of In Utero, Nirvana did fall apart, and they did it in the most tragic, heartbreaking, traumatizing way. But before the unimaginable happened, Nirvana made another all-out rock masterpiece, one that can comfortably stand next to or even above Nevermind in the pantheon that the band was so reticent to join. On top of that, In Utero had hits. "Heart-Shaped Box" was a hit, baby!

In the months after Nevermind went supernova, all the major labels in America went on a hunt for the mythical Next Nirvana, the underground band who could take things to new heights yet again. Patrons of scuzzy rock clubs got used to spotting A&R people who didn't know how to dress for the occasion, and every band that Kurt Cobain ever namechecked got big-money offers. Seattle bands like the Melvins and Mudhoney got corporate deals. Rick Rubin signed Flipper, the Cobain-beloved noise-punk band whose singer had died five years earlier and who had absolutely zero shot at crossover stardom, to his Def American imprint. Helmet, a skronk-metal band who'd put out one album on the Amphetamine Reptile label, became the focus of a label bidding war and eventually got a million-dollar advance from Interscope. (Helmet's only Modern Rock chart hit, the sick-ass 1992 banger "Unsung," peaked at #29.)

Meanwhile, the real Nirvana were still out there, but they were increasingly uncomfortable with their new societal role. Geffen wanted to put more Nirvana product on shelves, but when the band didn't turn in a follow-up album in time for the 1992 Christmas rush, Geffen put out Incesticide, a collection of the band's older loose tracks. Incesticide didn't get much of a promo push, since Nevermind was still selling and new singles were still going into rotation. But Incesticide still eventually went platinum, and "Sliver," a song that Nirvana originally released as a single in 1990, peaked at #19.

Nirvana, meanwhile, were still doing everything in their power to align themselves with underground-extremist types. In 1992, the band released the tellingly titled track "Oh, The Guilt" on a split 7" with Chicagoan drool-crunch miscreants the Jesus Lizard and put it out on Touch And Go Records. ("Puss," the Jesus Lizard's contribution, is a real smacker.) In 1993, Kurt Cobain teamed up with wizened beat-poet type William S. Burroughs to release a collaborative noise-piece known as "The 'Priest' They Called Him" on the even smaller Tim/Kerr label. You probably will not have much fun listening to that one. Whenever anyone would try to compare him to his rough contemporary Eddie Vedder, Cobain would say something cryptically dismissive. It was rude, but at the same time, Vedder wasn't doing stuff like that. Cobain was way more into being an avant-garde artist than being a celebrity, and you can hear that in In Utero.

In between Nevermind and In Utero, Cobain and his bandmates weren't talking too much -- partly because they were living in different places, with Cobain spending most of his time in LA, and partly because they weren't on the best terms. They didn't do much touring behind Nevermind because they didn't have to work hard to sell the album. Also, Cobain restructured the band's contract situation so that he'd get the vast majority of publishing royalties, which didn't leave the other two guys feeling great. But Nirvana had fun when they all went down to Brazil early in 1993, playing a pair of rock festivals with a bunch of other American alt-rock bands in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. They had a week off between those festivals, and they took that time to lay down a bunch of rough demos in a Brazilian studio. People who heard those demos thought that Cobain was just fucking around and making noise, but the demo version of "Heart-Shaped Box," while plenty noisy, already has lots of the built-and-burst intensity of the final product.

Cobain wrote "Heart-Shaped Box" in the LA apartment that he shared with his new bride Courtney Love in 1992. (Love's band Hole will eventually appear in this column.) Cobain would go into their big closet and work on guitar riffs, and Love has said that the "Heart-Shaped Box" riff was originally written for a Hole song and that she was pissed off when Cobain kept it for himself. Cobain once claimed that he wrote the song's lyrics after watching documentaries about kids with cancer, since those images gave him terrible, freaked-out feelings. But there's also a decent chance that "Heart-Shaped Box" is a tortured love song, of sorts. There's a story about how Love, upon hearing that Cobain was newly single, wooed him by sending him a heart-shaped box full of romantic-poetic items. In 2012, Lana Del Rey, someone who will eventually appear in this column if I keep writing it for long enough, covered "Heart-Shaped Box," and Love tweeted this at her: "you do know the song is about my vagina right?" She also said that she contributed "some of the lyrics about my vagina."

So: "Heart-Shaped Box" is a love song about kids with cancer and also about Courtney Love's vagina. Sure. Checks out. "Heart-Shaped Box" is a relic of an era when rock songwriters didn't feel the need to explain everything and when audiences had been trained not to expect literal breakdowns of those lyrics. I think there's a strong possibility that Cobain didn't really know what he was talking about when he wrote that song, that he tapped into subconscious feelings that resisted ideas of explanation. He did, however, explain the chorus: "Hey! Wait! I've got a new complaint!" To Cobain, that bit was a satire of how he was portrayed in the media. Cobain figured that he was seen as the complainer guy, the guy who hated being famous and who was never happy. The hook steered right into that, but it sure didn't sound like a self-aware joke. The "forever in debt to your priceless advice" part does sound ironic, and that's apparently a passive-aggressive thing that he would say during arguments. I bet it really sucked to argue with Kurt Cobain.

Mostly, Cobain's "Heart-Shaped Box" lyrics are a tangle of freaked-out body imagery -- meat-eating orchids, an umbilical noose, a broken hymen, a cancer that he wishes he could eat. Cobain's narrator is drawn to the magnet tar-pit trap of this gooey, gloppy, hungry humanity, and he's also repulsed. It's a confused, conflicted, spun-around rumination on the ways that people's bodies work -- a glimpse at the brain of someone who's always felt betrayed by his own body and who was always messing around with his own internal chemistry. On top of all of that, this person had just become a father and seen some of the more intense miracle-of-life action up close. Those ugly fascinations, whether presented coherently or not, don't often serve as the basis for catchy rock songs, but that's the magic of Nirvana. Whether or not they meant to do it, they took lots of heavy, heady ideas and presented them in ways that sounded great on the radio.

Cobain came up with the "Heart-Shaped Box" riff before he conjured any of that imagery, and the riff is ultimately what drives the song. It's a sinister slither that seethes and then explodes. Cobain was always dismissive of the tenets of the verse-chorus-verse song structure, and he characterized his own use of quiet-to-loud catharsis as a ripoff of the Pixies. But he was a master of the form, and the Pixies never did the slow-burn into the surge quite like Nirvana. The "Heart-Shaped Box" intro sounds like a dark, inviting glimmer. On the verses, Cobain's guitar and Krist Novoselic's bass circle each other warily. Then the hammer drops, and the two of them lock in completely while Dave Grohl beats the fuck out of his drums. It's got all the muscular ferocity and hidden seductiveness of a great metal song. Cobain thought of himself as much more punk than metal, but the growl-purr dynamics of "Heart-Shaped Box" are the kind of thing that a Black Sabbath fan could love.

All the advance hype surrounding In Utero was about Nirvana's choice of collaborator. Steve Albini made his name as the leader of the acerbic, misanthropic Chicago band Big Black, and he spent decades recording hundreds upon hundreds of underground rock records. Albini was a scientist of room-sound. He knew just where to put the mics so that guitars and drums would hit with the right level of severity, and he disdained the "producer" tag, insisting that he be credited as a mere recording engineer. Albini was also a vocal critic of the major-label system, and an early '90s op-ed that he wrote for Maximumrocknroll is a classic of that kind of polemic. But Albini was still down to work with major-label artists, even ones whose music that he disdained, as long as they agreed to his parameters.

Before he actually contacted Albini to talk about the possibility of making a Nirvana record, Kurt Cobain said that he wanted to do it, and the chatter got loud enough that Albini put out a statement saying that he'd heard nothing about such an enterprise. Soon afterward, Cobain reached out to Albini, and Albini, not a fan of Nirvana, wrote the band a letter about how he'd approach such a task. Albini said that he wanted to help them if they truly intended to bang out a record in a few days with minimal record-label interference, but that he didn't want to be associated with a product that would be remixed to death after his initial work. Albini also famously told Nirvana that he considered it "ethically indefensible" for a producer to take royalties on a record: "I would like to be paid like a plumber." Considering what In Utero eventually sold, that decision cost him a giant pile of money, but it also allowed him to sleep at night.

Given all of this, you can just imagine how attractive the Albini process must've been to Kurt Cobain. Cobain especially wanted Albini because Albini had worked on a couple of his favorite records, the Pixies' Surfer Rosa and the Breeders' Pod. Shortly before he worked on In Utero, Albini also recorded PJ Harvey's sophomore album Rid Of Me, and his bracing, spartan style did wonders for her. Albini got the job, and he went with the Nirvana guys to Pachyderm Studios, a relatively isolated complex an hour's drive away from Minneapolis. Albini suggested that studio. At the time, Cobain was trying to kick heroin, and the calculation was that he couldn't get in any trouble at a place where nobody would recognize the band.

In 2023, Conan O'Brien, whose late-night show started a few days after Nirvana released In Utero, got together with Dave Grohl, Krist Novoselic, and Steve Albini to talk about making the album on O'Brien's podcast. It's such a trip to hear those four guys discussing that album, not least because O'Brien was probably just as important to my own still-forming sensibilities as Nirvana was. Also, that conversation cannot happen again, since Albini is no longer with us. The recording session only took a few weeks, though Albini thought they should've been even faster than that. They were in a remote, frozen Minnesota location in February, and the only people around for most of it were the band, Albini, and Albini's technician and Shellac bandmate Bob Weston. On that podcast, they talk about the things that they'd do to pass the time, like lighting each other's hands on fire with Albini's tape-cleaning fluid, or prank-calling Gene Simmons, Evan Dando, and Eddie Vedder. (Those tapes must still exist somewhere.) Albini said that Cobain would record his vocal takes while playing a broken acoustic guitar, just for his own comfort, so you can apparently hear some acoustic guitar deep in the mix even on the loudest songs. Maybe that's why even the noisiest, most damaged In Utero tracks still have a certain vulnerable melodic core.

Legend has it that Nirvana's bosses at DGC heard the In Utero tapes and thought that the band was joking. Cobain's famous quote was "the grown-ups didn't like it." Different press outlets ran stories about how the label didn't think the album was fit to be released, and the Nirvana members themselves had misgivings about what they'd made. Eventually, they decided to get Scott Litt, the R.E.M. producer whose work has been in this column, to remix the songs that they considered to be potential singles. This pissed off the always-opinionated Steve Albini, who considered this to be a violation of his terms. Nirvana made a big point of saying that their label was not pressuring them to change the album, to the point where they bought a Billboard ad to insist that everything was good. In the meantime, Kurt Cobain recorded some extra vocals and guitar at Litt's Seattle studio; "Heart-Shaped Box" is the only In Utero track to feature anything that wasn't recorded with Albini.

From the very beginning, Nirvana thought of "Heart-Shaped Box" as a potential single. In the initial demo that the band recorded in Brazil, Kurt Cobain played a frayed, scuzzed-up guitar solo, and Krist Novoselic objected, saying that Cobain had made this beautiful song and then spoiled it with what sounded like an abortion thrown on the floor. (This band loved its visceral imagery.) To my ears, the Albini mix of "Heart-Shaped Box" doesn't sound that different from the final product, but maybe that's why I'm not a rock legend. To those guys, every little audio decision matters. As a kid, I loved the idea of Nirvana going up against their label to release this nasty, uncompromising album. There's no pre-planned release narrative that could've grabbed my imagination quite like that. I wonder how much of that was exaggerated, how much was amped up in the press specifically to appeal to consumers like me. I'm guessing that some version of this conflict really did happen, but the best way to sell things to people in that early alt-rock era was to insist that you had no interest in selling them things. That's why In Utero was the first album that I ever bought on the day it came out. I could not wait to ride my bike to the record store and pick it up that Tuesday.

When In Utero came out in September 1993, "Heart-Shaped Box" had already been out in the world for a few weeks. Nirvana enlisted Depeche Mode/U2 collaborator Anton Corbijn to direct the song's video, but Corbijn said that many of the visual ideas came from Cobain himself. (Past Nirvana collaborator Kevin Kerslake sued the band, claiming that some of those visual ideas came from the treatment that he proposed; they settled out of court after Cobain died.) Those images are often nightmarish -- the crucified old man, the fetuses growing on a tree, the little girl in what appears to be KKK robes. But it's also got Kurt Cobain looking like a zillion bucks, even when he's out of focus. Despite all those intentionally alienating touches, Cobain still has the same rock-star magnetism that came through so clearly in the "Smells Like Teen Spirit" clip. The jeans that Cobain wore in the clip are apparently now the most expensive jeans in the world. "Heart-Shaped Box" might be the most unsettling, avant-garde video that Beavis and Butt-Head ever loved, even if it gave Beavis nightmares.

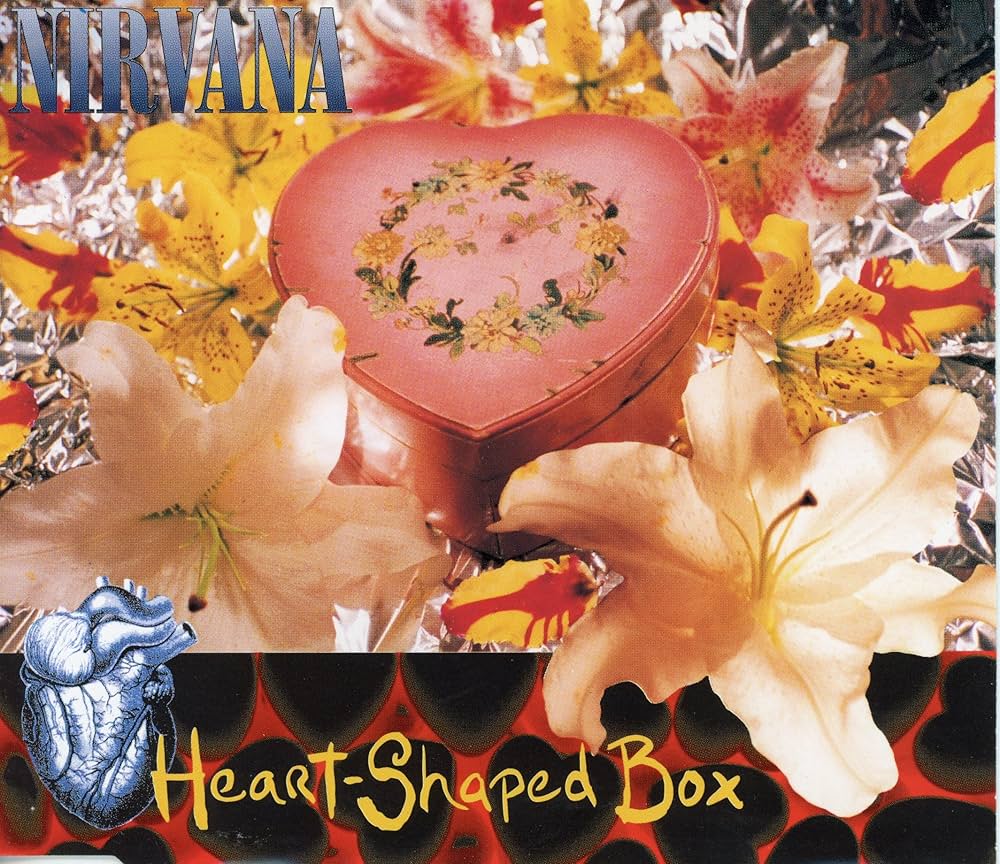

The thorniness of In Utero was key to the album's appeal. Walmart and Kmart refused to sell the CD until the band changed the back-cover artwork and the title of "Rape Me," but that just got more press attention for the record. In Utero debuted at #1. "Heart-Shaped Box" was never released as a single in the US, so it never touched the Hot 100, but it was a top-10 hit in a few European countries, including the UK. The single did well across the rock-radio spectrum. It was pretty much guaranteed to reach #1 on the Modern Rock charts before too long -- a big change from a couple of years earlier, when "Smells Like Teen Spirit" barely eked out a week at #1.

Around the time that they released In Utero, Nirvana added the former Germs guitarist Pat Smear as a touring member, and they played "Heart-Shaped Box" on a Saturday Night Live episode that Charles Barkley hosted. They kicked off an American tour at the Arizona State Fair, and they mostly hit big theaters and smaller arenas. Critics loved In Utero. It came in at #2 on the 1992 Pazz & Jop poll, beating everything except Liz Phair's Exile In Guyville. (PJ Harvey's aforementioned Rid Of Me, another Albini-engineered record, came in at #3.) On the singles poll, "Heart-Shaped Box" tied the Digable Planets' "Rebirth Of Slick (Cool Like Dat)" at #2 -- behind the Breeders' "Cannonball," ahead of Dr. Dre's "Nuthin' But A 'G' Thang."

In January 1994, Nirvana dressed up in suits to appear on the cover of Rolling Stone. In the accompanying profile, Kurt Cobain insisted that he was happier than he'd ever been. This was not the case. As it happens, "Heart-Shaped Box" was the last song that Nirvana ever played live. They played it at the end of a Munich show in March 1994. Three days after that show, Kurt Cobain overdosed in Rome. Two months after that, Cobain was dead. We'll have to talk about all that before long, when Nirvana return to this column.

GRADE: 10/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's Patti Smith singing a huge, intense version of "Heart-Shaped Box" at a 2000 show in Seattle:

(Patti Smith's only Modern Rock chart hit, 1988's "Up There Down There," peaked at #6. It's an 8.)

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Last month the surviving members of Nirvana reunited to play the SNL50 concert, with Post Malone standing in for Kurt Cobain. That was weird, right? He did a serviceable-enough job, but it was Post Malone standing in for Kurt Cobain. I wonder if they'll do any more of that. There was a context for this: In 2020, Posty did a pandemic livestream show where he put together a band and played a bunch of Nirvana covers. It was a nice moment. Here's Post Malone's perfectly solid take on "Heart-Shaped Box":

(If I keep writing this column for long enough, Post Malone will eventually appear in this space.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: I am a hopeless mark for edgily violent superhero TV shows, so I was happy when The Boys ended its most recent season last year with a montage set to "Heart-Shaped Box." It's obviously packed with spoilers, and it's also got a guy smacking someone in the face with his gigantic prehensile penis. But if you're OK with both of those things, here's that montage:

THE NUMBER TWOS: The Breeders, Nirvana's opening act on their In Utero tour, peaked at #2 behind "Heart-Shaped Box" with their ecstatic sugary-spiky non-sequitur fuzz-bomb "Cannonball." Can you believe that shit? "Heart-Shaped Box" and "Cannonball" all over the radio at the exact same time? We had no idea how good we had it. I know you, little libertine, and you know "Cannonball" is a 10.