June 11, 1994

- STAYED AT #1:1 Week

In The Alternative Number Ones, I'm reviewing every #1 single in the history of the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks/Alternative Songs, starting with the moment that the chart launched in 1988. This column is a companion piece to The Number Ones, and it's for members only. Thank you to everyone who's helping to keep Stereogum afloat.

"My pals and I experienced a potent combo of shock, mirth, and disgust that provided months of entertainment. You know that feeling you get when a giraffe in leopard-print panties comes roaring down the street on a unicycle? Same deal here, only more so." That's Sam McPheeters, a writer whose work I deeply enjoy, discussing what it was like to watch Green Day explode in 1994. (It's from his book Mutations: The Many Strange Faces Of Hardcore Punk, which I recommend without reservation.) At the time, McPheeters was the leader of Born Against, a raw and noisy punk band that played the same DIY venues as the pre-explosion version of Green Day -- including 924 Gilman St., the collective-run Berkeley nonprofit venue that the band accidentally made famous. He was also a columnist for Maximumrocknroll, the all-important Bay Area zine that presided over Green Day's excommunication from the punk scene that had nurtured them. Like so many others, McPheeters was not into this Green Day shit.

To guys like McPheeters, the Dookie experience was a surreal mindfuck, a thing that should not be. Green Day were a Gilman band, and now they were on the radio? And reporters were showing up to Gilman to ask questions about them? Something had gone terribly wrong in the universe. Honestly, I should not summarize the viewpoint of a man who can lay it out just fine for himself. This is how McPheeters describes the experience of watching a bloc of Green Day videos long after the band's global takeover:

In the seventeen years since I'd paid attention to them, Green Day had somehow morphed into something immense and terrible, a mewling behemoth that embodied the worst aspects of pop music: the preposterous pomposity of '90s alt-plop, the cock rock awfulness of '80s arena schlock, the preening sincerity of '70s singer-songwriter ballads. Worse, they'd done so with the tenacity of a cockroach, refusing to die, or even peak.

I love it. I don't agree, but I love it, and I respect it. That kind of stridency, beautifully expressed, is the sort of emotion that a seismic event like Green Day's ascent should inspire. In that chapter, McPheeters describes his relationship with the late Maximumrocknroll founder Tim Yohannon, whose cancer Green Day celebrated on record, and he takes the long way around to finding some respect for Green Day by way of their documentary about the miraculous East Bay punk scene from whence they sprang -- a respect that goes far beyond "begrudging." When Green Day suddenly and forcefully stormed the gates of popular culture, it was like someone playing out the Nirvana career arc in fast-forward, only without the heroin and with an even more purist-fundamentalist hometown base that resented their every move. But Green Day never self-destructed. Instead, they became such an institution that they are now welcome back at Gilman once again.

From a certain perspective, Green Day's rise was freaky and inexplicable as it was happening. In retrospect, it feels absolutely inevitable. They were the right band at the right time, and they offered a joyous and charismatic hook-attack that complemented everything else on alt-rock radio even as it stood out starkly. Green Day were always too catchy and too ambitious to remain creatures of the underground. When the underground forcefully ejected them, they had no choice but to become one of the biggest bands on the planet. If their major-label run didn't work out, they couldn't hang it up and go back home, since home now regarded them as pariahs. They had to succeed, so they did. That process naturally starts with a song about being so bored and lonely that even jerking off doesn't even feel good anymore.

Even when they were a Gilman band, Green Day were never for guys like Sam McPheeters, whether they knew it or not. I listen to a whole lot of DIY punk, and very little of it has the same charm and verve and mercenary melodic sensibility as Green Day's early records. Long before Green Day made the major-label leap, Billie Joe Armstrong and Mike Dirnt were hitting skyward harmonies, while Dirnt was adding extra riffs and melodic layers that you almost never hear from a bassist in a band on their level. By the time they signed, Green Day were selling more records and packing more people into their shows than what the infrastructure of their world could comfortably handle. But that infrastructure was what allowed Green Day to become a band in the first place. It might even be what allowed them to function as people. Context puts them in a fascinating predicament -- the giant band who came from the place where the very idea of being a giant band was unthinkable.

Any discussion of Green Day has to begin with a discussion of 924 Gilman St. The aforementioned Maximumrocknroll founder Tim Yohannon, a Berkeley punk elder with ties to the Bay Area's long tradition of radical leftist politics, helped launch Gilman in the late '80s, recruiting volunteers and turning a former supermarket and industrial storage space into an all-ages community center that was run in ways that reflected the values of that community. Places like Gilman function as their own ecosystems, as hubs for everything happening around them. Every city with a decent punk and/or hardcore scene has at least one space like that; they are absolutely necessary. Gilman was part of a self-sustaining system that included the MRR zine, the Epicenter record store, labels like Lookout!, and distributors like Mordam. Most of these things were run, at least initially, less like businesses and more like cooperative community organizations, complete with fussed-over charters and long, divisive meetings. Despite the tedium that organizations like this necessarily engender, that kind of community can be an absolute revelation to a young person in search of something. It can feel like paradise.

Even in its early days, Gilman existed at the center of an entire mythology, a place full of larger-than-life characters and exciting bands. I've never been to Gilman, but I've watched about a million grainy videos shot inside its walls. In my mind, it looms largest as the home of Operation Ivy, the great ska-punk band whose bassist and singer/guitarist went on to form Rancid. Operation Ivy lived their whole two-year life in Gilman, only managing to tour the United States once, and that did not stop them from attaining legend status. Tons of other bands treated Gilman as their home venue: Crimpshrine, Pansy Division, Jawbreaker, Neurosis, Blatz, the Mr. T Experience. Those bands didn't necessarily sound anything like each other, which was part of the point. The space encouraged exploration in some realms while maintaining orthodoxy in others. It's a remarkable institution, one that's still going strong today. I know a guy who books hardcore shows at Gilman right now.

When the young members of Green Day needed a place to go, Gilman was right there. Billie Joe Armstrong was the youngest of six kids in a working-class family in Rodeo, California, a little East Bay town outside Berkeley. His mother was a waitress, and his father was a truck driver who died of cancer when Billie Joe was 10. Around the same time that he lost his father, Billie Joe met a kid named Michael Pritchard in his school cafeteria. (Pritchard is his real name, and Mike Dirnt is his punk name -- taken because "dirnt" is the sound that his bass makes.) They were into Van Halen and Judas Priest, and they learned about stuff like the Ramones together. Both of them had rough, chaotic home lives, and both of them dropped out of high school and moved out of their houses when they were still kids. Eventually, they both found their way to Gilman.

Before dropping out of high school, Armstrong and Dirnt started a band with a couple of their classmates. At first, they called themselves Blood Rage, after a slasher flick, and then Sweet Children -- a good name since they were literal children at the time. When the classmates left the band, Dirnt moved from guitar to bass, and John Kilmeyer, ex-drummer of the local hardcore band Isocracy, joined up. One of Armstrong's older sisters led them to Gilman for the first time, and Armstrong and Dirnt became regulars there -- first as kids at the shows, and then as a band that would play there sometimes. Sweet Children played their first show in 1987, at the barbecue joint where Armstrong's mother worked. In 1988, Larry Livermore, co-founder of the Lookout! lavel, signed the young band.

Larry Livermore, another onetime MRR columnist, is an important supporting character in Green Day's story -- an aging ex-hippie weirdo who'd moved from San Francisco to the sleepy weed-farming hodbed of Humboldt County. Before he started the Lookout! label in 1987, Livermore published the Lookout zine, and he led a band called the Lookouts. That band's drummer was Frank Edwin Wright III, a Humboldt County kid who was 11 when Livermore recruited him. Wright took the punk name Tre Cool, and he seemingly never matured much past 11. Livermore convinced Sweet Children that they should change their name because there was already another punk band called Sweet Baby that played at Gilman. Without giving it much thought, they picked the name Green Day, which was just what they'd call an entire day dedicated to smoking weed. It's a pretty terrible band name, but it has served them well anyway. In 1989, the newly rechristened Green Day released their debut EP 1,000 Hours.

Sounds familiar, right? From the very beginning, Green Day played a version of punk that basically functioned as high-octane power-pop, bashing out fast, giddy, catchy songs about boredom and self-loathing. Those same topics were plenty popular among the gargling, heaving grunge scene that was taking shape a few hundred thousand miles north, but Green Day never treated those subjects the way that bands like Nirvana did. Even when Green Day sang about self-loathing, they did it with fire and commitment, and they sounded like they were having fun. They were having fun -- the same kind of fun that similarly snotty and hooky DIY punk bands like Screeching Weasel and the Queers were having around the same time. Green Day were broke and dirty and bummy, but they'd found their place in the world. They got to take part in the scene that gave them the kind of acceptance and love that they'd never had at home. That's a powerful thing. If you find that at the right age, it sticks with you for your whole life. It becomes a feeling that you chase.

The first time that Green Day played under the Green Day name, it was at Gilman, opening for Operation Ivy, their favorite band, at Op Ivy's famous final show. (It blows my mind that you can now just pull up a grainy YouTube video of that last Operation Ivy set, but here it is.) Green Day followed the 1,000 Hours EP with a full-length called 39/Smooth in 1990, and they started touring the US, something that MRR made possible. MRR used to publish a regularly updated DIY-show guide called Book Your Own Fucking Life, a directory that would tell you if there was, let's say, a pizza place in Peoria that you might be able to play while passing through town. In the pre-internet days, you'd call the number in the book, and maybe you'd find a floor where you could crash that night. The shows might not all be magical, and you definitely wouldn't make any money, but that was a life that you could live.

Eventually, John Kilmeyer went off to college, and Tre Cool started filling in for him before becoming a full member of the band. Cool was younger than Kilmeyer. He was also a better drummer, and he smoked weed, which Kilmeyer did not. His dad owned a bookmobile, and the band would borrow it to go on tour. He was a good fit. Green Day released a second album called Kerplunk at the end of 1991, and it was a word-of-mouth success that sold something like 50,000 copies -- a major success on a DIY level. That kind of thing was possible even before the internet came into the equation. Bands from the punk underground didn't get the same kind of press attention that skronky and experimental indie rockers might command, but they often had bigger audiences. Kids would tell other kids, and then a few hundred of those kids would show up to see a band like Green Day play in a warehouse or a backyard. Green Day made it over to Europe and spent months playing squats and warehouses. College radio started playing their tracks. Things were happening.

Former Operation Ivy member Tim Armstrong -- no relation -- tried to poach Billie Joe and recruit him as the guitarist for the new band Rancid, but Green Day were doing well enough that Billie Joe declined the invitation. He still co-wrote "Radio," one of Rancid's best songs. (Rancid's highest-charting Modern Rock hit, 1995's "Time Bomb," peaked at #8. It's a 10.) In 1993, Green Day got to play to big crowds as the opening act for Bad Religion, California punk standard-bearers who'd done the unthinkable and signed to a major label during the post-Nirvana feeding frenzy. (Bad Religion's highest-charting Modern Rock hit, 1994's "21st Century (Digital Boy)," peaked at #11.) Those same major labels started talking to Green Day, who were already popular enough that the familiar punk institutions couldn't really accommodate them. Before the band fully understood what was happening, three different corporations were competing for their services.

Green Day didn't understand the major-label world, and they didn't click with the A&R reps who took them out to dinner. But they did get along with Rob Cavallo, a young guy who worked for the Warner subsidiary Reprise. Cavallo's father was a former Prince manager and one of the producers of the Purple Rain movie, so Rob was fully immersed in the big-deal pop world, but his sensibility was close enough to that of the Green Day kids that they all got along. Green Day accepted the Reprise deal in front of them, and they got to work in a real studio for the first time in their lives.

As this was happening, the MRR and Gilman faithful turned against Green Day. They played their last Gilman show in 1993, and then they were officially banned from the venue. MRR published an entire issue on the evils of major labels, and someone wrote "Billie Joe must die" on the wall of the girls' bathroom in Gilman. They could never go home again. Green Day co-produced their 1994 album Dookie with Cavallo, and they re-recorded the Kerplunk! track "Welcome To Paradise," a starry-eyed ode to the scene where they were no longer welcome. Later on, that song reached #7 on the Modern Rock chart. (It's a 10.)

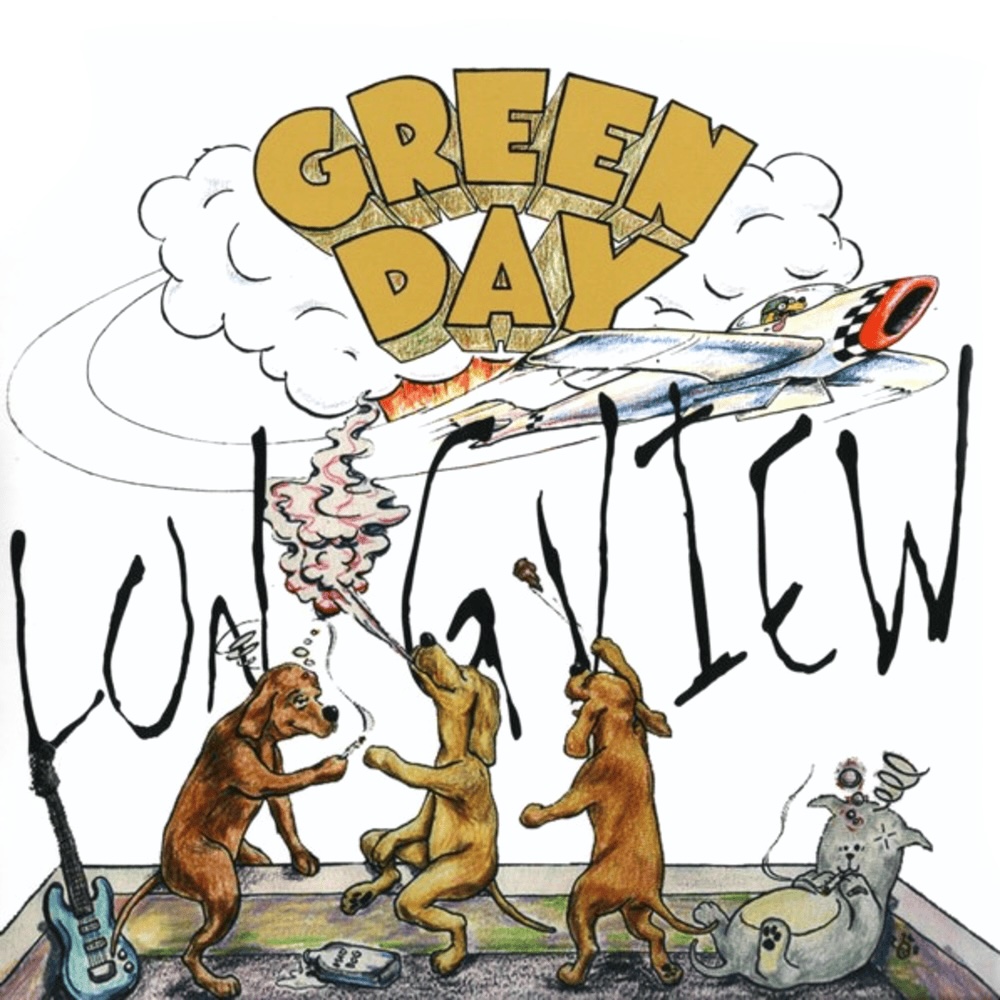

If you're reading this column, chances are you don't need me to tell you about Dookie. Dookie is a great fucking album, and it's one of the biggest records to come out of the '90s alt-rock boom. It hit like a bomb, and then it kept hitting, to the point where half the songs on the album made their way into radio rotation. We'll get to a handful of them in this column. In a way, lead single "Longview" is the least typical song on all of Dookie. It's the longest and the slowest, and it's the one with that ridiculous bassline -- ba-dern-dern-dern-dern.

Legend has it that Mike Dirnt came up with the "Longview" bassline when he was tripping on acid. The other guys in the band went out to a movie, and they came home to Dirnt sitting on the floor with his bass, insisting that he'd figured it out, man. The bassline sounds like a cartoon duck spinning in circles until it falls down, and Tre Cool meets it with an all-toms drum-rumble that wouldn't be out of place in the swing revival that came a few years later. If you were writing a song about being stuck at home and halfway enjoying your own torpor, you couldn't ask for a better backing track than that.

On "Longview," Billie Joe Armstrong sings about being bored and jerking off, two instantly relatable subjects. In the context of circa-'94 alt-rock radio, where most bands were deep into their own inscrutable poetry, it felt good to hear someone braying about sitting at home and watching the tube when nothing's on. It's a song about stasis, about being stuck by yourself and figuring out that you don't like the company. Armstrong constantly runs himself down. He smells like shit, he's fuckin' lazy and fuckin' lonely, he's got no motivation, he locked the door to his own cell and lost the key. When the guitars come rushing onto the chorus, he finds some escape -- biting his lip, closing his eyes, getting that easiest of quick endorphin rushes. By the time the song is over, though, masturbation has lost its fun. But even in its jizz-rag squalor, "Longview" is exciting. Its quiet-to-loud structure isn't quite the same as what was already established as the Nirvana house style. It's too loopy, too silly. When Green Day lock in on the chorus, they sound like they've found a more sustainable kind of escape. When Armstrong and Mike Dirnt hit those harmonies about having no motivation, there's joy in their voices. It remains unspoken, but they have each other. That's something.

Green Day had "Longview" sitting around for a while. The song is named after Longview, Washington, a logging town where Green Day would play a restaurant or a keg party once a year when they were coming up. That's where they played "Longview" for the first time. When they first tried to record the song, it didn't work, but they bashed it into shape while opening for Bad Religion. When "Longview" made its way onto the radio, I had no idea that it was supposed to be a punk song. I'd already started reading rock criticism and buying Bad Brains records, so I thought I knew what that term meant, and it didn't apply to this fun new song about jerking off, the one where the radio version was full of bleeps but you could always tell what he was saying. I thought it was just a fun, fizzy alt-pop song, and it sounded just right next to James or Weezer or Material Issue.

MTV got on board before radio did. I remember another kid in eighth grade trying to tell me about the "Longview" video, saying that the guys in Green Day looked "scary." When I saw it, they didn't look scary to me. They looked aspirational. The clip came from Mark Kohr, a director who'd already done some videos for fellow Bay Area trio Primus. (Primus' highest-charting Modern Rock hit, 1993's "My Name Is Mud," has a Mark Kohr video. That track peaked at #9. It's an 8.) Kohr filmed Green Day in the apartment where Billie Joe Armstrong and Tre Cool lived, and that gives it a crucial lived-in feeling. Young Armstrong is a cutie-pie, but Kohr films him and his bandmates in harsh light that almost exaggerates any paleness and acne. Armstrong is a magnetic presence on camera, and he radiates the pent-up desperation that he sings about on the song. There's a monkey that runs around -- Armstrong's idea, a visual "spanking the monkey" pun -- but Armstrong just ignores it. Eventually, on sheer destructive impulse, he stabs the shit out of his couch and then slumps down in it while feathers rain down around him. It's great TV. In their appreciation of the "Longview" video, Beavis and Butt-Head did some of their best work.

On alt-rock radio, "Longview" was catchy and buoyant. It used plain language to express things that the other radio bands would only reference through allusion. Something that I really appreciated about Green Day and about the punk bands that followed them into the spotlight was that they didn't disappear into depression the way that the grunge bands did. They might be depressed, and they would acknowledge that, but it was always something to fight against, an impediment in the pursuit of fun. I got more of that from Rancid, whose mutual-support gang-chant shit had the same swagger I heard in rap, than from Green Day. But even though "Longview" is really a bitch session on paper, it hits like a pep talk. That worked on me.

"Longview" connected right away. By the time that the song got its one week atop the Modern Rock chart, Dookie was already gold. It would sell many, many more copies after that. As the album started to blow up, Green Day got a slot opening the main stage on the Lollapalooza tour -- but only the second half of the tour. Lolla founder Perry Farrell, someone who's been in this column a bunch of times, was dead-set on booking the Boredoms, the great Japanese experimentalists who were arguably the freakiest band to ride the post-Nirvana wave onto a major label. Farrell did not like Green Day, and he somehow thought they were a Geffen-assembled boy band. Earlier this year, Stereogum ran an excerpt of Richard Bienstock and Tom Beaujour's very fun Lolla oral history. Armstrong talks about how Farrell was a "fucking asshole" who tried everything in his power to keep Green Day off the tour: "I think that made us want to play it even more, actually, because we wanted to prove that he had his head very far up his own ass." That's a good motivator.

Historically, Lollapalooza was very good at finding bands to play in the early main-stage slots -- Pearl Jam in '92, Rage Against The Machine and Tool in '93, Green Day in '94. My first Lollapalooza was '95, when the main-stage openers were the Mighty Mighty Bosstones -- not game-changers like the others I just mentioned, but a band that would have a solid impact on the world. (We'll see the Bosstones in this column eventually.) In '96, it was Psychotica, and we're running into some problems there.

By most accounts, Green Day absolutely crushed in that opening Lollapalooza spot. They got big reactions at Lollapalooza, and they got an even bigger reaction when they played at Woodstock '94 in August. By that time, they had another song on the radio, so we'll talk about that when Green Day return to this column.

GRADE: 9/10

BONUS BEATS: This doesn't have anything to do with "Longview" specifically, but this week's mainline Number Ones column also happened to cover a young game-changer named Billie -- one who will appear in this column a bunch of times if I keep doing it long enough. Those two Billies happen to be mutual fans, so here's a 2019 Rolling Stone video of the two of them gushing over one another:

(Shout out to Stereogum Discord user One_True_Link for that one; I was just going to use the Beavis And Butt-Head video commentary as the Bonus Beat before I saw that one.)