September 24, 1994

- STAYED AT #1:5 Weeks

In The Alternative Number Ones, I'm reviewing every #1 single in the history of the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks/Alternative Songs, starting with the moment that the chart launched in 1988. This column is a companion piece to The Number Ones, and it's for members only. Thank you to everyone who's helping to keep Stereogum afloat.

Dan Rather didn't know what the fuck was going on. All he knew was that someone was beating him up while repeatedly saying something that didn't make any sense at all. In the fall of 1986, Rather was one of the most recognizable men in America. Every weeknight, Rather hosted CBS Evening News, one of three network news shows that millions upon millions of people watched while eating their dinner. (My house was a Peter Jennings house, but I personally liked Rather the best.) Rather had covered the JFK assassination, Nixon's trip to China, Watergate, and the Challenger explosion. He'd been attacked before. At the Democratic National Convention in 1968, a security guard punched Rather in the stomach live on air while he was trying to interview a delegate. I'm sure that wasn't fun, but Rather at least had some context for what was happening there. On this night in 1986, context simply didn't exist. The two guys attacking Rather didn't even seem to recognize him. They thought Rather was some guy named Kenneth.

"Kenneth, what is the frequency?" That's what one of the men wanted to know. Dan Rather had met a friend for dinner, and he was heading home, walking down Park Avenue in Manhattan. Two well-dressed men walked up to him, and one of them asked him that question. Rather told them that they had the wrong guy, and the man who'd asked him the frequency punched him in the jaw and knocked him down. Rather took off running into the lobby of his building, but the two men chased him inside and repeatedly kicked him in the back. Rather called for help, and his building's doorman and super rushed to his aid. Rather had money on him, but the two men didn't rob him. The two men ran off, and they were never caught. Police were absolutely baffled. They couldn't even figure out a motive.

Rather got patched up at the hospital. The attack happened on a weekend, and he was back on TV the following Monday to report on Ronald Reagan's upcoming meeting with Mikhail Gorbachev in Iceland. He told the viewing audience that he'd been attacked that weekend and that he didn't know why. For years, nobody knew why. It was a freaky little occurrence that went viral in the way that things could go viral in the pre-internet era. It was fodder for newspaper cartoons and columns, none of which could make any sense of what had happened. R.E.M. frontman Michael Stipe once referred to the attack as "the premier unsolved American surrealist act of the 20th century." But then the surrealist act was solved, and the reality was even stranger than it first appeared.

In August 1994, about a week before R.E.M. released their song "What's The Frequency, Kenneth?," a man named William Tager shot and killed a stagehand outside the Today show studio at Rockefeller Plaza. Tager had an assault rifle, and he was trying to get into the studio; the stagehand who he murdered was trying to keep him out. When Tager was arrested, he told police that NBC had been broadcasting secret messages into his head and that he was looking for ways to block them. Later on, Tager told a prison psychiatrist that he'd been sent from the future, using experimental technology to travel nearly 200 years backward through time. Tager also admitted to attacking Dan Rather. He said that he really did have the wrong guy. He thought Rather was someone named Kenneth Burrow, the vice president of the future world. The statute of limitations was up, so Tager was never charged with assaulting Rather, but Rather later saw a picture of Tager and said that he was definitely one of the guys who'd attacked him. We still don't know the identity of the second guy.

R.E.M. didn't know anything about William Tager when they wrote their song "What's The Frequency, Kenneth?" At that point, the attack on Dan Rather was still a mystery, though it was already plenty freaky. To R.E.M., the attack and the nonsense phrase were signals that someone was utterly disconnected from the world in which he lived. Michael Stipe said, "I wrote that protagonist as a guy who’s desperately trying to understand what motivates the younger generation, who has gone to great lengths to try and figure them out, and at the end of the song it’s completely fucking bogus. He got nowhere." In that moment, R.E.M. were going through their own identity-crisis situation. They'd become beloved elders in the alt-rock era -- the word-of-mouth underground sensation who pushed their way to no-shit pop stardom and who inspired and cast shadows over all the younger rock outsiders who emerged in their wake. R.E.M. still wanted to function as a band, and they had to figure out how.

"What's The Frequency, Kenneth?" is a song about the confusion that can come out of being in such a strange position. Nobody is more overwhelmed by mass-media barrage than by the people who have to exist at the center of cultural attention, and it's a song about that. So maybe it's appropriate that the story behind "What's The Frequency, Kenneth?" turned out to be bigger than R.E.M. could've possibly realized. Maybe Michael Stipe understood, on some paranormal level, that he was really singing about a guy who was so convinced that he was living in his own personal Terminator movie that the idea drove him into a murderous rage against the people whose job it was to deliver him the news. If "What's The Frequency, Kenneth?" was a song about disconnect, then it only makes sense for that disconnect to run to deeper, stranger places than the world realized.

R.E.M. weren't the first band to make music inspired by the attack on Dan Rather. In 1987, the California power pop band Game Theory opened their album Lolita Nation with a brief, experimental skit called "Kenneth, What's The Frequency?" That track isn't about the attack on Dan Rather any more than the R.E.M. song is. In both cases, though, the allusion is undeniable. I was a kid when all this happened, and I don't even remember the attack on Dan Rather as anything other than the inspiration of the R.E.M. song. But it's pretty clear that the phrase immediately resonated, at least in some circles, as a shorthand reference to talk about how fucked up and unpredictable the world could be.

In 1994, R.E.M. had plenty of opportunity to consider the fucked up, unpredictable nature of the world. They were mainstays on alternative rock radio, and their music had grown in popularity even as it had become quieter and more insular. The chiming, depressive folk-rock of Out Of Time and Automatic For The People turned R.E.M. into unlikely international superstars. Kurt Cobain cited them as paragons of virtue, "saints" -- the one band who came up from the underground and figured out how to be famous with grace and humility. While those albums took off, R.E.M., once a tireless touring institution, took a protracted break from the road. While touring behind 1988's Green, they played bigger venues than the ones where they thought they belonged, and the process exhausted them. They made Out Of Time and Automatic For The People while sequestering themselves in the studio. When they played live, it was either for a TV promotional hit or for a random friends-and-family one-off. But by 1993, they wanted to get back on the road, and they knew that would bring them to venues even bigger than the ones that they played while touring on Green. If they were going to do that, they knew they couldn't keep making chamber-folk. They would need to make a loud rock record instead.

Drummer Bill Berry was apparently the one pushing for a tour. He could see that the members of R.E.M. were all heading off in different directions. Berry bought a farm outside the band's Athens, Georgia hometown, and he spent most of his time there. Guitarist Peter Buck divorced his first wife and fell in love with the owner of the Crocodile Café, a legendary Seattle rock club. Their twin daughters were born in 1994. (Buck's first wife owned Athens' equally legendary 40 Watt Club. He had a type.) Michael Stipe was getting more and more comfortable with his celebrity, hanging out with world leaders and starting a film production company. Later in the '90s, Stipe would serve as an executive producer of movies like Man In The Moon, Velvet Goldmine, and Being John Malkovich. Mike Mills joined up with a bunch of fellow alt-rock all-stars -- the Afghan Whigs' Greg Dulli, Sonic Youth's Thurston Moore, Nirvana's Dave Grohl, Gumball's Don Fleming -- to cover a bunch of old songs on the soundtrack to the early-Beatles biopic Backbeat. Maybe a tour would bring all four R.E.M. members back together on a deeper level.

The members of R.E.M. thought that their big rock tour might even be their last hurrah. As they prepared to head out, Bill Berry told Rolling Stone, "It will be interesting to see how we feel after this tour. If it’s like the last one [laughs]... you might not hear a record out of us for quite a while. We may break up. This is the first record since Green where there’s a tour involved and that’s as important as the record itself... Now, we go out and see if we still have it onstage live. That’s going to be the test. Ask me in a year, and I’ll tell you."

In 1993, the members of R.E.M. got together in Acapulco to decide how things were going to go for the next few years, and they laid out their plan. At one point, Automatic For The People was supposed to be a loud rock record, too, but that wasn't how things turned out. If they made a third straight album of downbeat jangles, then their live show would be boring, so now they had to commit. Peter Buck had to put down the mandolin and pick up the electric guitar. They looked at how U2, arguably their closest peers, reinvented themselves, shedding their sincerity and playing with theatrical flash on their own 1991 album Achtung Baby, and they thought about what their version would be. Eventually, they got back together with longtime producer Scott Litt in New Orleans, cranking out demos and figuring out how their new album should sound.

R.E.M. had a ticking clock in front of them. A grand-scale world tour is a huge commitment, and the plans were already underway by the time they hit the studio. The album had to be finished and released before the tour could start, which meant the band had a hard deadline. They'd written previous records while touring, but they weren't touring anymore, so they had to come up with all the music for the new one on the spot. There were complications. River Phoenix died, and then Kurt Cobain died. Michael Stipe was friends with both of them. He was especially close with Phoenix, whose sudden passing left him unable to write for months. Ultimately, the LP Monster would be dedicated to Phoenix's memory. When recording sessions got underway, various band members' health issues kept interrupting the flow -- appendicitis for Mike Mills, the flu for Bill Berry, an abscessed tooth for Stipe. There are lots of reports that "What's The Frequency, Kenneth?" slows down at the end because Mills, not yet realizing that he needed his appendix removed, was hit by waves of pain in the studio. (Mills later said that wasn't the case.)

R.E.M. wanted to contend with the new wave of alternative rock that they'd helped usher in, and they found fascinating ways to approach it. Monster isn't a grunge album, but you can hear its echoes in the level of fuzz on Peter Buck's guitar. In the band's Rolling Stone cover story, Buck talked a bit about trying to figure out where R.E.M. fit into the mid-'90s landscape: "We all talked about it and realized that we are a rock 'n' roll band, and for better or worse, we wanted to reapproach that. We decided we wanted to make an uptempo electric record but without using any elements of heavy metal, which none of us ever listened to. So much of what’s happening now, all those bands liked the Ramones and Black Sabbath. I’m not sure I’ve ever heard a Black Sabbath record. So we’re into a weird, purist, no metal whatsoever, very little blues, white rock roll thing." There's precious little jangle to be found on Monster. Instead, Buck plays in a loud tremolo blare, while Mike Mills and Bill Berry attempt a glam-adjacent shimmy. It's not evident on "What's The Frequency, Kenneth?," but Michael Stipe sings more about sex than he ever had or ever would in the future.

Stipe wasn't just thinking about sex. He also considered pressures that his younger peers faced. He told Rolling Stone, "I feel so much like a contemporary of those guys, and yet I also feel like I’ve been there a little bit. I have great sympathy for anybody who’s been thrown into… this as quickly as Kurt and Eddie have been. They got, in a way, the same tag that I did, where I was being positioned as the voice of a generation. It was something that I really, really did not want. It was like 'Wait a minute -- I’m a fucking singer in a rock 'n' roll band. I did not ask for this.' It’s a lot of pressure. If Murmur or Reckoning had sold five million copies, I wouldn’t be alive to tell the tale."

Kurt Cobain wasn't alive to tell the tale. He took his own life while R.E.M. were recording Monster, and he reportedly had an Automatic For The People CD on repeat in the room where he died. For Monster, R.E.M. wrote a song called "Let Me In" about Cobain. Courtney Love sent Mike Mills a guitar that once belonged to Cobain, and that's what he played on the record -- upside-down, since Cobain was left-handed. Point is: R.E.M. had a lot of shit going on, but they were specifically trying not to make a despondent, depressed record. So maybe "What's The Frequency, Kenneth?," the opening track and lead single from Monster, is about trying to find some sense of life and exuberance within the overwhelm.

I never really had any idea what Michael Stipe was talking about on "What's The Frequency, Kenneth?" before I researched this column. I knew about the reference to the Dan Rather attack, and Stipe really belts out the title line. Beyond that, though, you can barely understand a word that comes out of the man's mouth. The song is a mushmouthed syllable-attack, and not in the knowingly mysterious way that R.E.M.'s records once were. Nobody knew all the words to "It's The End Of The World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine)," either, but you at least got the gist of the machine-gun cultural references. On "What's The Frequency," though, Stipe just sounds like he's making sounds. When you see the lyrics written down, they're easier to parse. Stipe's narrator doesn't understand the world around him, the malaise festering within younger folk. He never understood the frequency.

At one point, Stipe laments, "You said that irony was the shackles of youth." We don't know who "you" is supposed to be in that line, but gen-X irony was a big cultural conversation point in that moment. The mass media, still a monocultural proposition in that moment, reduced Generation X to a bundle of tics and signifiers, throwing the word "slacker" around as if it meant something. The narrative was too simplistic and linear. The "you" of the song could be anyone from the older generation who attempted to impose that narrative. It could even be Dan Rather.

On the song, Stipe quotes another generational-voice type from that cultural moment: Richard Linklater, the indie filmmaker responsible for 1990's Slacker, which despite its title is not some generational cartoon. Slacker is a plotless tone poem that simply follows young people around Austin. The camera lingers with one character for a while, and then that character passes someone else on the street, and then we follow that second person for a time, and the first one never shows up again. That shit blew my mind when I was a kid. On "What's The Frequency," Stipe quotes a Linklater line from the Slacker script, and he only mentions Linklater by first name: "I studied your cartoons, radio, music, TV, movies, magazines/ Richard said, 'Withdrawal in disgust is not the same as apathy.'" Linklater's quoted line is just a quick moment in Slacker; some guy reads it off an Oblique Strategies card that a stranger hands him.

Later on, Michael Stipe told Dan Rather about that Richard Linklater quote: "There was a world-wear, dystopic kind of 'fuck it all' feeling coming out of grunge and coming out of that generation. The song was about someone who was trying to tap into that and not doing it very well." Apathy and disgusted withdrawal might not be the same thing, but they often have the same effect. They're both coping strategies. Neither of them work. Instead, on this glorious morning, we're all watching a 33-year-old Democratic Socialist preparing to become the next mayor of New York City, absolutely stomping on a sclerotic party establishment in the process. Fuck apathy, and fuck withdrawal in disgust. Even in the darkest of moments, the possibility of great things happening, of triumph, remains. Zohran Mamdani just dunked on Andrew Cuomo so hard that he shattered the backboard. That doesn't have anything directly to do with "What's The Frequency, Kenneth?," but I can't publish a column that touches on these issues this morning without addressing it.

Anyway. The magic trick of "What's The Frequency, Kenneth?" is that it turns confused disdain, even malaise, into an absolute headrush. Peter Buck's opening guitar riff is a furious fuzz-chime that has always reminded me a bit of something J Mascis might've done for Dinosaur Jr. It might be the loudest thing on the track, and everything else is arranged around it -- the quietly complex hard-strut bassline, the hip-shaking tambourine, the ahhh-ahhh backup vocals, the ripples of tremolo that Buck overdubbed in. It's got a great hallucinatory guitar solo that Buck played forwards and then backwards, which only adds to the disorientation. Even with its garbled lyrics about disconnection, "What's The Frequency" registers as an anthem. Its charged-up energy was a hard left turn for R.E.M., and it didn't sound like anything else in the band's discography -- not even like the winky '80s pop songs like "Superman" or "Stand." It's a rock song about being unable to find connection, but it still connects. I don't think it's one of R.E.M.'s best, but when I hear it played loud on a car stereo on a sunny day, you could maybe convince me.

The "What's The Frequency, Kenneth?" video came from longtime R.E.M. collaborator Peter Case, and it's a pretty bare-bones affair -- just the band playing in a room, with strobe lights flashing on them. But it works as its own kind of fame commentary. For much of the clip, Case lines up the shot so that Michael Stipe's head is not in the frame. Instead, the main thing that you see is his T-shirt -- a star against a plain background.

You might imagine that Dan Rather would not be thrilled to hear that someone made a hit song out of the nonsensical phrase that someone yelled while beating him up, but he had a good sense of humor about the whole thing. In 1995, R.E.M. played Madison Square Garden, and Rather joined them at soundcheck. He tried to sing "What's The Frequency, Kenneth?," and he couldn't get the cadence at all. Someone filmed the moment, and Rather's CBS colleague David Letterman aired it. Years later, Rather interviewed Michael Stipe and Mike Mills about the track, and he still seemed to think the whole saga was pretty fun.

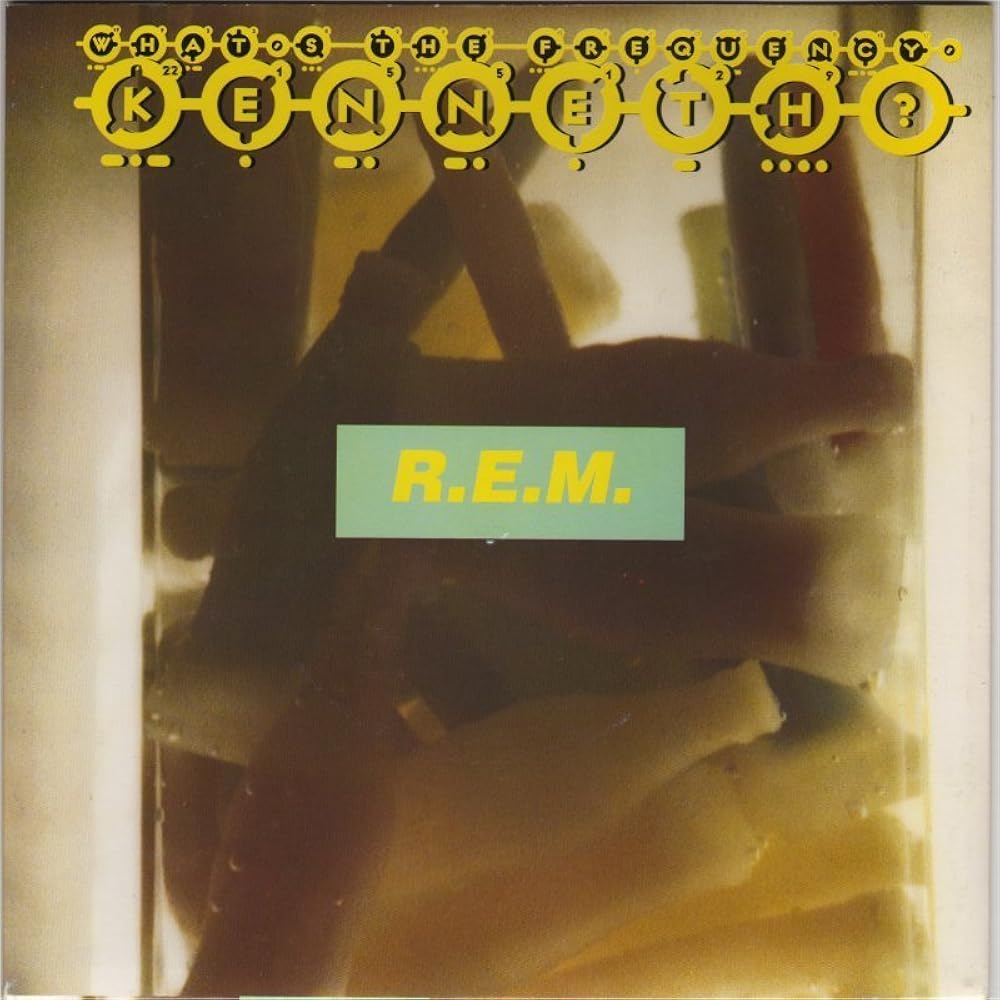

"What's The Frequency, Kenneth?" really was a hit, too. Naturally, people really had to wrestle with their feelings over the song; it got some puzzled reactions. Today, that song and Monster as a whole are pretty divisive within the larger arc of the band's history. In the moment, though, R.E.M. had built up a tremendous amount of goodwill, and "What's The Frequency" fit in pretty nicely with all the other loud, catchy songs on alt-rock radio. "What's The Frequency" knocked Green Day's "Basket Case" out of the top spot when it became the first song ever to debut at #1 on the Modern Rock chart. "What's The Frequency" also made it to #2 on the Mainstream Rock chart and #21 on the Hot 100 -- higher than any of the singles from Automatic For The People. Monster came out a couple of weeks after "What's The Frequency" hit radio, and it sold hundreds of thousands of copies in its first week. For the moment, R.E.M. were still just as big as all the younger bands that now looked to them as role models, and they still had more hits on deck. We'll see them in this column again soon.

GRADE: 8/10

BONUS BEATS: I was light on Bonus Beats options for this one -- nobody covers a song when nobody knows the words -- but I really wanted to use the body of this column to get into the "What's The Frequency, Kenneth?" needledrop in the 2018 movie Under The Silver Lake. The film is a kind of hallucinatory neo-noir, and it's all about the slippery nature of reality in a world where nobody can agree on the truth and conspiratorial thinking isn't necessarily the domain of nutcases. Those themes pair extremely well with the song, especially since we've only disappeared further down the disinformation superhighway in the years since both "What's The Frequency, Kenneth?" and Under The Silver Lake came out. I really need to give that one a rewatch. Anyway, here's the very fun scene where Andrew Garfield, high out of his mind, dances to the song with Grace Van Patten:

(Cornershop's absolute banger "Brimful Of Asha," the other song in that scene, peaked at #16 in 1998.)