March 2, 1996

- STAYED AT #1:1 Week

In The Alternative Number Ones, I’m reviewing every #1 single in the history of the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks/Alternative Songs, starting with the moment that the chart launched in 1988. This column is a companion piece to The Number Ones, and it’s for members only. Thank you to everyone who’s helping to keep Stereogum afloat.

Even among the paralyzingly self-aware class of alternative rock stars who blundered into positions of profound cultural importance in the early '90s, nobody thought more about what it meant to be an alternative rock star than Billy Corgan. Corgan and his band Smashing Pumpkins didn't come from any particular scene, and they didn't sound that much like any of their contemporaries. But they had the good fortune to be swept up in the grunge hype-wave, and then they released one of the definitive albums of that wave. Despite all that, Corgan didn't think like a grunge guy. He didn't shy away from stardom. Instead, he wanted to achieve absolute greatness -- defined, at least somewhere in his head, as making everyone like him.

Of course, the irony there is that probably nobody who came out of that alt-rock moment, with the possible exception of Corgan's friend and collaborator Courtney Love, is as widely or openly disliked as Billy Corgan. Earlier this year, Stereogum published an excerpt from Richard Bienstock and Tom Beaujour's extremely fun oral history of the Lollapalooza tour. The Smashing Pumpkins headlined Lolla in 1994, the year when that festival was at its cultural peak, and seemingly everyone else on the tour hated that band in general and Corgan in particular. The excerpt we published is basically just one long procession of people talking shit about Corgan, and it probably could've been five times longer.

I have never met Billy Corgan. I have no idea what he's like in person, then or now. I can only really go on interview quotes and secondhand anecdotes. By his own account, Corgan was always a perpetual outcast, a guy who couldn't hang. He was a control freak when it came to his own band, and he was openly dismissive of many of those who might've considered themselves his peers. Here, for instance, is something Corgan said when he was on the cover of SPIN in 1996: "In 1991, at least we were competing with the real deal. Now, we’re competing with Nirvana mimics. It’s a game you don’t even want to play. It’s not honorable." That's so obnoxious and so awesome at the same time. You don't have to respect that sentiment if you don't want to, but I have to respect it. I have no choice.

I'm sure that a great many people had good reasons for disliking Billy Corgan, but I think some of that ambient loathing came down to ambition. Corgan came along at a moment when it wasn't cool to have ambition, and he had so much of it. Some of that ambition was commercial. Corgan wanted to sell more than the people who looked down on him, and he accomplished that goal. Some of it was also societal. Billy Corgan wanted to write the songs that defined an era. He accomplished that, too. But it just so happened that the era was one where you weren't supposed to want that.

From my outside perspective, many of the things that people didn't like about Corgan were the same things that drove him to make vast, epic rock records in the first place. When Corgan was on the cover of both SPIN and Rolling Stone, he was there to talk about Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness, the colossal and absurd double album that the Smashing Pumpkins released in October 1995. At the time, the very idea of an alt-rock band making a huge double album -- triple, if you bought it on vinyl -- was considered ridiculous. Corgan knew that, and he steered right into it.

Mellon Collie wears its pretensions on its sleeve. It's right there in the goofy-ass title, the Renaissance-looking cover art, and the opulent sweep of the songs themselves. I'd just turned 16 when Mellon Collie came out, and I was happy to dismiss it as rockstar wankery. Today, I have to say that this fucking thing rules. It's not one of those double albums that would work better if you edited half of it out. The hit rate on the record is crazy, and quite a few of its songs became actual radio mainstays, tracks that are now written into my DNA simply because I was a teenager when they came out. That doesn't happen often. It's an achievement that shouldn't be overlooked.

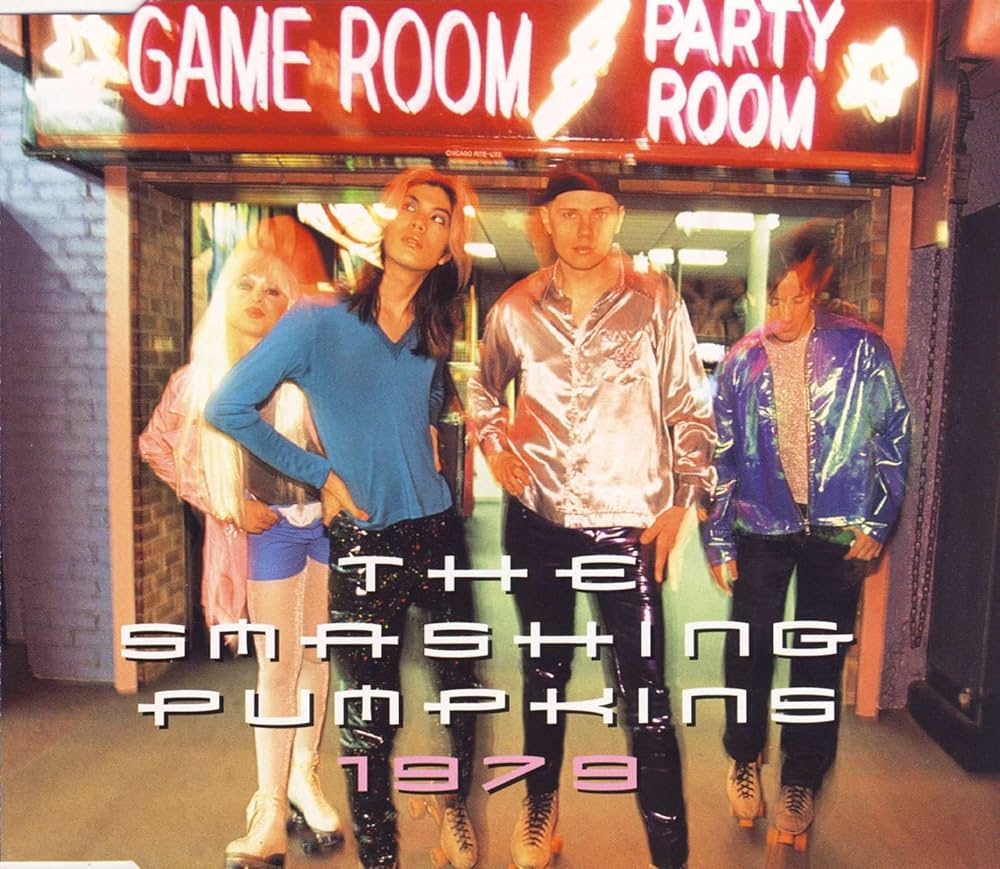

Bizarrely, this is the only time that the Smashing Pumpkins will appear in this column. They were absolutely, inarguably one of the defining alt-rock bands of their era, and they were all over the airwaves when when modern rock radio was at its peak. The Smashing Pumpkins had 17 top-ten hits on the Billboard Modern Rock chart. (Will I give all of those songs ratings in this column? We'll see! Probably not, though! That seems like too many!) Four different Pumpkins singles stalled out at #2. Despite all their rage, the Pumpkins only landed atop that chart for a single week of their entire decades-long existence, and they did it with a quiet little shrug of a song.

Still, that quiet little shrug of a song was ambitious in its own way. It found Corgan reaching outside of his usual skillset to capture a feeling of lost youth. That song was never one of my favorites, but it feels inextricably tied to my own now-lost youth. "1979," named for the year that Corgan turned 12 and I turned zero, doesn't really sound like any other Smashing Pumpkins songs, before or since. It doesn't sound too much like anyone else's songs, either. It's still the biggest hit that Corgan ever made. Maybe Corgan didn't really succeed in making everyone like him, but he did make a bunch of songs that very few people can deny, and "1979" is one of them. Maybe that's really what he wanted all along.

William Patrick Corgan, the son of a blues-rock guitarist, grew up around Chicago, usually living with either grandparents or a stepmother. His father wasn't around much. He was a big kid, and he was good at baseball when he was young. He stopped liking baseball when other kids caught up to his level on the field, so he got into playing guitar instead. Corgan never got into punk, even though he was the right age. Instead, he liked parking-lot dirt-metal, and he became a goth when goth first became something that you could be. For a little while in the mid-'80s, Corgan moved to Florida and fronted a goth band called the Marked. That didn't last long, so he moved back to Chicago and got a job in a record store. That's where he met James Iha.

Co-workers Corgan and Iha started writing goth-pop songs together, and they called themselves the Smashing Pumpkins. Corgan met bassist D'arcy Wretzky outside a club, and their first conversation was an argument about the Dan Reed Network, a top-40 rock band in the '80s. (Wretzky liked them; Corgan was dismissive.) The trio played a few shows with a drum machine backing them up, but to get a gig at the Metro, the great Chicago club, the owner told them they needed a real drummer. A mutual friend set them up with Jimmy Chamberlin, a jazz-trained drummer with a gift for bashing. The fit was a weird one, since Chamberlin was a regular-dude rocker who didn't know anything about alternative music and who had a good job as a carpenter. He was older than the rest of them, too. But Chamberlin knew what he was doing, and Corgan quickly realized that the Pumpkins sounded a whole lot better with Chamberlin on board. Also, I think it's cool that there's a James and a Jimmy in the band -- the full spectrum.

Once they had a solid lineup, the Smashing Pumpkins moved toward a heavy, smeary, driving psych-rock sound. Their debut single "I Am One" came out on the Chicago indie Limited Potential -- funny name, given the context. That song sounded at least a little bit like Jane's Addiction in its sonic scope, its groovy crunch-riffage, and Corgan's nasal whine of a voice. The Pumpkins quickly found sound powerful management, and one of their first shows was actually opening for Jane's Addiction in Chicago. This did not especially endear them to Chicago's noise-rock scene, which was fully of acerbic firebrands like Steve Albini and David Yow. Bands who came out of that world generally didn't show signs of rock-star ambition -- or if they did, then they showed it ironically, like Urge Overkill. Corgan wanted it, and that helped him make plenty of enemies.

The Smashing Pumpkins released one more single, 1990's "Tristessa," as part of the Sub Pop Singles Series, and then they signed with Caroline, a Virgin imprint that effectively operated as a fake indie label and as a distributor for real indie labels. They recorded their 1991 debut album Gish with producer Butch Vig, and it came out about four months before Nirvana released their own Vig-produced LP Nevermind. Corgan reportedly played most of the Gish guitar and bass parts himself, which cannot have been good for internal band chemistry. Nevertheless, Gish is absolutely fucking awesome. It's a starry-eyed guitar-rock record that travels the strange netherzone between Zeppelin and shoegaze. The reviews were strong, and so were the sales, at least on an underground level. The single "Rhinoceros" even got enough Modern Rock airplay to reach #27. Eight years after its release, Gish went platinum; a lot of people went back and filled in their Pumpkins blanks.

When alternative rock first became a cultural force, the Smashing Pumpkins were right there. Corgan and Courtney Love dated for a little while in 1991, before Love met Kurt Cobain. That same year, the Smashing Pumpkins went out on tour with the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Pearl Jam, and that was a pretty good tour to be on. A year later, the Pumpkins were one of the few non-Seattle acts to appear on the Singles soundtrack. Their contribution "Drown" is probably still my favorite Pumpkins song ever, and it charted at #24. The band had a ton of momentum when they went back into the lab with Butch Vig and made their sophomore LP Siamese Dream.

Whoo baby, Siamese Dream! That's an album right there! Apparently, it was a nightmare to make. Once again, James Iha and D'arcy Wretzky apparently didn't play much of anything on the record. The two of them were a couple for a little while, but they broke up shortly before recording, which must've made everything worse. Jimmy Chamberlin, who did play on the record, was strung all the way out. Apparently, the band recorded in Georgia partially so that he wouldn't be able to find drugs there, but then he went ahead and found drugs anyway. Billy Corgan, meanwhile, was going through severe depression and panic attacks, and he dealt with it by living in the studio, working obsessively to find the right guitar tone, and spending hundreds of thousands of dollars of his label's money. (The Pumpkins had been upstreamed from Catherine to Virgin, so at least the money was there.) But all that shit went into a gorgeous whirlwind of a rock record, which made all of them famous.

Siamese Dream came out in summer 1993, got glowing reviews, and was almost immediately all over the radio. Lead single "Cherub Rock," a pissy attack on the Chicago indie rock scene, reached #7, and the twinkling hammer-down anthem "Today" followed it to #4. ("Cherub Rock" is a 9, and "Today" is a 10.) I remember the string-drenched ballad "Disarm" being everywhere, but it apparently only reached #8, though it stayed on the alt-rock charts longer than the other two. (It's a 7.) On the Pazz & Jop poll, critics voted Siamese Dream the 11th-best album of 1993, putting it right in the middle of a boho alt-rap sandwich, between Digable Planets' Reachin' (A New Refutation of Time and Space) and PM Dawn's The Bliss Album …? Within a few years of its release, Siamese Dream sold four million copies in the US.

Plenty of underground rockers, even the ones who were publicly nice to grunge stars like Pearl Jam, treated the newly huge Smashing Pumpkins with outright derision and dismissal, and Pavement went so far as to clown them in their "Range Life" lyrics. Billy Corgan took particular offense at the Pavement thing, though he denied rumors that he'd had them kicked off the 1994 Lollapalooza tour. (Pavement played Lolla in '95 instead, and they had a bad time. My first Lollapalooza show was the one in West Virginia where Pavement's set ended in a deluge of thrown trash and mud.) Corgan told Rolling Stone, "It’s like high school all over again. You have the football team, except the football team is the guys in Pavement and Mudhoney. And they’re all patting themselves on the back for how cool they are instead of healthily challenging themselves to greater heights." I love this quote. Everything about it is funny.

At this point, Billy Corgan had great songs flowing out of him -- too many to be contained within regular album cycles. Smashing Pumpkins singles typically included lots of bonus tracks, and even the band's 1994 odds-and-ends collection Pisces Iscariot went platinum. It also sent one song, a tender acoustic cover of Fleetwood Mac's "Landslide," to #3 on the Modern Rock chart. (It's an 8.) When Corgan started the process of recording the all-important Siamese Dream follow-up, he had dozens of songs and grand intentions to make what he literally called "The Wall for generation X." I don't quite know what that means, but I just barely qualify for gen-X status by the skin of my teeth, and I would much rather listen to Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness than The Wall.

After making two albums with Butch Vig, Billy Corgan went out and found new producers for Mellon Collie: Alan Moulder and Flood, two masters at the art of translating messy, adventurous sounds into something more sleek and streamlined. Moulder was especially good at shaping oceanic guitar noises, a task he'd done for shoegaze giants My Bloody Valentine and Ride. He'd also mixed Siamese Dream, so he had experience with the specific kind of guitar squall that Corgan liked. Flood, meanwhile, has been in this column a bunch of times, most recently for Depeche Mode's "Walking In My Shoes." He was just coming off his work on PJ Harvey's To Bring You My Love, the most critically acclaimed album of 1995.

After Corgan sidelined his bandmates on the two previous Smashing Pumpkins records, he made an effort to make them more part of the process for Mellon Collie. James Iha even got to write a song and a half and to sing lead on "Take Me Down," the only one that he wrote by himself. Mellon Collie is arranged into two parts, Dawn To Dusk and Twilight To Starlight, though I've never been able to detect any particular vibe-shift between them. Aesthetically, the record goes all over the place. It's got plenty of the vrooming, exploding guitar sounds that the world expected, but there's a ton of other stuff, too -- strings, synths, proggy affectations. On the whole, it sounds just a bit more mechanized than anything the Pumpkins had made to that point. And it had "1979," a tender little reverie that stands alone.

Billy Corgan has a podcast now. Earlier this year, he interviewed Marilu Henner, an actress with a near-photographic memory. Henner told Corgan the exact day that she first heard "1979" -- just a couple of weeks before it reached #1 -- and Corgan mentioned that the song itself was his meditation on a very specific memory that had lived in his head for years. Corgan didn't write "1979" about the actual year 1979; I'm guessing he just picked that year because it rhymed. Instead, he talked about a moment a few years after that: "I was 17 or 18 years old, and I was stuck at a light on North Avenue heading into the city, and it was raining. It was one of those dreary Chicago days where it's cold and it's just raining and I'm watching the wipers go like this and I'm at a red light, and that's the memory I wrote the song from. It was such a specific moment in my life emotionally… It was this feeling of I'm leaving one life and I'm going towards this other life, and it's just that 60 seconds of my life where I felt a cleaving of energies -- one is receding, and one is coming."

We all have memories like that -- tiny and specific moments that stick with us, sometimes for no particular reason. We can look back and invest those moments with great import, even if there's no particular thing that would make them stand out to anyone else. What Corgan remembered was feeling like he stood on a precipice, waiting for his chance to achieve the thing that nobody thought he could achieve. In Corgan's internal narrative, it always seems to be him against the world. I don't know if that's always healthy, but he certainly harnessed that narrative and put it to use. Maybe the reason "1979" is such a gentle, reassuring song is that it's not about Corgan overcoming the naysayers. It's about a quiet, reflective moment when he had to sit and marinate in his own impatience, in the doubt that he'd ever become the person that he wanted to be.

"1979" was the last song that Corgan wrote for Mellon Collie. He had demoed an earlier version of the track, and he and his collaborators were trying to winnow the album down into the gigantic 28-song, two-hour megalith that it became. Flood didn't think the track was good enough, so Corgan took a few hours that night and rewrote it -- partially, he later admitted, to prove Flood wrong. The song is relatively skeletal by Pumpkins standards. It starts out with a rickety drum loop, and Jimmy Chamberlin then played live drums over that loop. There's a sample in there, too -- Corgan's own voice, treated and warped enough that it sounds like he's talking in his sleep, or maybe singing underwater. I remember trying to make out what words Corgan was singing in that sample before giving up. I was right to give up. The sample is wordless.

In a way, "1979" is a musical cousin of the records that Billy Corgan loved in that moment at the red light. He loved the Cure and New Order, and that kind of heart-on-sleeve synthpop was the shit in Chicago at the time. Maybe he had The Top or Power, Corruption & Lies on his car stereo in that moment. Today, "1979" almost works like chillwave -- a digital evocation of childhood innocence, rendered as a dream-distorted image of whatever floated through the air in the moment being evoked.

As "1979" builds, it adds smears of keyboard and guitar, but it never really gets loud. Instead, it's a nostalgia-drunk version of a pop song, and Corgan sings the whole thing with a warm sense of affection for his past self. His "1979" lyrics are disconnected shards of teenage-outcast imagery -- cool kids who never have the time, headlights pointed at the dawn, a girl who hung down with the freaks and ghouls. It's all hazy longing for a land of a thousand guilts and poured cement, which sure sounds like Chicago to me. He imagines himself forgotten, his bones turning to dust, on one of the songs that ensures that'll never happen. It's quite a trick.

"1979" wasn't an obvious smash, and it wasn't the first single from Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness. That honor went to "Bullet With Butterfly Wings," a ridiculous song that I like even more. "Bullet With Butterfly Wings" is almost defiantly mockable, with all of its overstated teenage lyrics about the world being a vampire and remaining a rat in a cage despite all your rage, etc. I definitely made fun of the song when it was out, but the silliness is exactly what's awesome about it. As the years keep flying by, I figure out that I'm not cooler or cleverer than a song like that, that it really hits on a deep level. "Bullet With Butterfly Wings" was a huge radio song, but it didn't quite do well enough to get a column of its own, peaking at #2. (It's a 10.)

"Bullet With Butterfly Wings" was a real-deal hit that got mainstream rock airplay and reached #22 on the Hot 100, becoming the first Smashing Pumpkins track to crack that chart. After that song's histrionics, "1979" sounded extremely low-key, but it went further and stuck around longer. Some of that was the video. The married directors Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris have already been in this column for making Jane's Addiction's "Been Caught Stealing" clip, and they later directed Alan Arkin to an Oscar in Little Miss Sunshine. For "1979," they film a beatifically beaming, newly bald Corgan, looking about as handsome as he ever has in his life, riding around in the back of an old car, bearing witness to a mob of unruly suburban kids having the sort of night that'll later serve as nostalgia-fuel. Thanks in part to that video, "1979" became the Pumpkins' biggest-ever hit, going #1 on both the Mainstream and Modern Rock charts and even climbing to #12 on the Hot 100 -- the Pumpkins' best career showing by far.

After the success of "1979," Mellon Collie kept spinning off more singles, and those singles stayed in radio rotation, too. "Zero," a rocker every bit as histrionic as "Bullet With Butterfly Wings," peaked at #9. (It's a 9.) "Tonight, Tonight" went even heavier on the orchestral flourishes than "Disarm" and reached #5. (It's a 6.) The soaringly romantic "Muzzle" charted at #8, while the muted ballad "Thirty-Three" went all the way to #2 more than a year after the album's release, even though I don't remember hearing it on the radio very much. ("Muzzle" is an 8, and "Thirty-Three" is a 33. No, I'm playing, it's a 6.)

Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness sold like crazy, leaving the Smashing Pumpkins' Siamese Dream numbers in the dirt. In 2012, Mellon Collie went diamond. That's a little illusory. Since it was a double album, the RIAA counted its sales twice. Still, that's five million units sold of a double CD; very few albums in the '90s alt-rock era had that kind of reach. At the 1996 Grammys, Mellon Collie and "1979" were nominated for Album and Record Of The Year, respectively. Mellon Collie lost to Céline Dion's Falling Into You, and "1979" lost to Eric Clapton's "Change The World," two extremely funny outcomes. The Pumpkins did get to perform "1979" on the show, though. America's critics gave Mellon Collie a suspicious kind of respect. On the 1995 Pazz & Jop poll, the album came in at #14, behind Sun Volt's Trace but ahead of Raekwon's Only Built 4 Cuban Linx.

Even when he was promoting Mellon Collie, Billy Corgan was already talking about moving onto the next thing. He held up "1979" as a taste of the band's future, telling SPIN, "We're just gonna throw out the rule book and start over. People keep asking us, 'What is it going to sound like?' We have no idea. I mean, '1979' is probably the only hint, something that combines technology, and a rock sensibility, and pop, and whatever, and hopefully clicks. Between 'Bullet' and '1979,' you have the bookends of the album. You’ve literally the end of the rock thing and the beginning of the new thing."

They really needed to do something new, too. The way things were going, the band was not a sustainable enterprise. The Pumpkins' Mellon Collie arena tour was one disaster after another. In Dublin, a girl died in the moshpit. In New York, Jimmy Chamberlin and touring keyboardist Jonathan Melvoin both overdosed on heroin. Melvoin died, and the band kicked Chamberlin out and kept the tour going.

The new musical direction started to reveal itself with the release of a couple of 1997 soundtrack songs. First came "Eye," the icy synthpop jam that the Smashing Pumpkins contributed to David Lynch's Lost Highway soundtrack. ("Eye" peaked at #8, and it's an 8.) Almost immediately afterward, they worked with Nellee Hooper on "The End Is The Beginning Is The End," their song for Joel Schumacher's Batman And Robin picture. Batman And Robin honestly doesn't have that much in common with Lost Highway beyond, I guess, a shared sense of ominous looming perversity. ("The End Is The Beginning Is The End" peaked at #4. It's a 6.)

The band completed their pivot into electronic sounds on their 1998 album Adore, which was at least a partial success. Adore went platinum, and two of its singles, "Ava Adore" and "Perfect," reached #3 on the Modern Rock chart. (They're both 7s.) But the Pumpkins pretty much immediately fell from their Mellon Collie peak, and they never got close to it again. Just after Jimmy Chamberlin returned to the group in 1999, D'arcy Wretzky left, and she's been living in near-total seclusion since then.

The Pumpkins replaced Wretzky with Hole's Melissa Auf der Maur and went back to big guitar sounds on 2000's Machina/The Machines Of God. Once again, they remained in alt-rock radio rotation. Lead single "The Everlasting Gaze" reached #4, and they made it to #2 with "Stand Inside Your Love." ("The Everlasting Gaze" is a 5, and "Stand Inside Your Love" is a 6.) But the Pumpkins' moment was over. Machina stalled out at gold, and Billy Corgan announced that they were breaking up, leading them through a farewell show at the Metro that lasted four and a half hours.

After the Smashing Pumpkins ended, Billy Corgan and Jimmy Chamberlin put together a group of hot-shit indie rock musicians and formed a new band called Zwan. They lasted long enough to release one album, 2003's Mary, Star Of The Sea, and to send one song, "Honestly," onto the alt-rock charts before dissolving acrimoniously and becoming a forever punchline. ("Honestly" peaked at #7. It's a 6.) I saw Zwan play a radio-station Christmas show in 2003, which must make me one of the few people who has seen Zwan in concert but who has never seen any iteration of the Smashing Pumpkins. I don't really remember anything about their set. Corgan's 2005 solo album TheFutureEmbrace -- these fucking titles, man -- didn't really go anywhere. In 2005, Corgan announced that he wanted to bring the Smashing Pumpkins back. Jimmy Chamberlin returned to the fold, but James Iha and D'arcy Wretzky did not. Neither did Melissa Auf der Maur, for that matter.

For a very long time, the rebooted Smashing Pumpkins kept going in this fashion, with Billy Corgan joined by a bunch of randos and usually Jimmy Chamberlin, except during the era when Chamberlin finally left the band. For a little while, they had Tommy Lee on drums. That was weird. I have never made a whole lot of time in my life for post-'90s Smashing Pumpkins records, but there are a lot of them. Some of them have even done pretty well on alternative rock radio, which might mean something if alt-rock radio hadn't been a diminished husk of its former self for the vast majority of its lifespan. The band's 2007 comeback single "Tarantula" even went all the way to #2. (It's a 4.) That was their last time in the top 10. Hey, look at that! I rated all the top-10 Smashing Pumpkins songs and the Zwan one! Your subscription dollars at work!

In 2018, James Iha and Jimmy Chamberlin returned to the Smashing Pumpkins, which meant that 75% of the original lineup is now back together. (D'arcy Wretzky, last I heard, lives on a farm in Michigan. In 2011, she was arrested for failing to control her wild horses.) The mostly reunited Smashing Pumpkins are still touring pretty big venues and putting out music, including a 2023 triple-album rock opera called Atum. They still regularly reach the Modern Rock chart, just not the top 10. Their most recent album Aghori Mhori Mei came out last year, and their single "Who Goes There" made it to #21 earlier this year.

Billy Corgan does a lot of stuff outside the context of his band. He makes occasional solo records. He owns a Chicago tea shop, where he sells crazy-expensive vinyl reissues to his most dedicated fans. He podcasts. He pursues unlikely passions. He's a pretty prominent promoter of independent pro wrestling, for instance. He's really into preserving the legacy of Bozo The Clown, for some reason. He went on Infowars a couple of times. He seems like a genuine American weirdo, and he's probably better off being that than trying to convince the world to like him.

GRADE: 9/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's Moby's pretty great 1996 remix of "1979," which seems largely built on the Billy Corgan voice sample from the original track, stretched out into a hiccuping moan:

(Moby's highest-charting Modern Rock hit, the 2000 Gwen Stefani collab "South Side," peaked at #3. It's an 8.)

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's partial audio of Billy Corgan's old buddies Pavement playing a snarky "1979" cover at a 1999 show:

(Pavemet's only Modern Rock hit, 1994's "Cut Your Hair," peaked at #10. It's an 8.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's the boy band Why Don't We's video for their 2020 single "Slow Down," which is built on a "1979" sample:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's the Savannah, Georgia rapper Duwap Kaine freaking a "1979" sample on his 2021 track "Genie":

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's a one-off band -- members of Touché Amoré, Alexisonfire, AFI, and Deafheaven -- doing a remote, hardcore-flavored "1979" cover for Jordan Olds' great Two Minutes To Late Night web series in 2023:

(AFI will eventually appear in this column.)